The Great Disappointment

The success of the reforms in ending balance-of-payments stress and raising the rate of growth has blinded attention to the fact that in one area reforms have had very little success. This is manufacturing.

By the 1980s it was apparent to all concerned that India’s economic performance was deficient when compared to that of East Asia, and not just Japan—which was already industrialised when India won freedom. Korea and Taiwan were not just exporting to the rest of the world, they were exporting high-quality manufactures based on electronics.

The Chinese example of exporting low-quality and low-cost household utensils was to come much later. Reading the annual “Economic Survey” of the Government of India at the time the reforms were launched suggests that the East Asian experience of growth through manufacturing success was positioned centrally on the radar of its architects.

The fact that reforms mostly contained measures that directly or indirectly affected the industry and trade sectors of the economy attest that. Of these, the dramatic reduction in tariffs and the complete elimination of quantitative controls were the most egregious changes in policy.

There are of course purely theoretical arguments for emphasising manufacturing.

Many years ago, Nicholas Kaldor observed that faster growth of manufacturing was associated with faster growth of labour productivity, suggesting a route to the prosperity which results when at least part of the growing productivity is passed on to labour in the form of higher wages. Moreover, for an economy such as India’s with a low land–man ratio, there is the added attraction that manufacturing is “land saving”.

Despite all this theoretical rationalisation, however, what must have tipped the balance towards manufacturing in the reforms of 1991 was most likely the spectacular manufacturing success of countries in the East.

Now, three decades after the reforms, a similar manufacturing success has avoided India. I have already referred to the far greater range of consumer goods, and of far higher quality, produced in India since 1991; but on one important count the reforms have failed to produce the expected result.

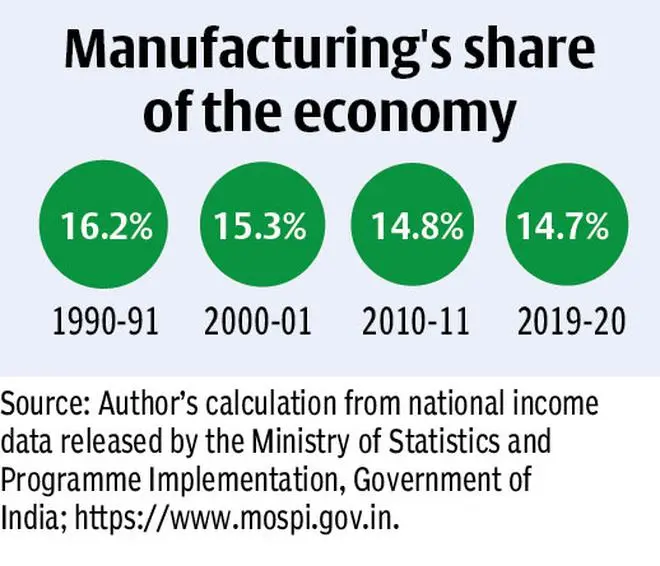

As seen in Table 3.2, the size of the manufacturing sector relative to the economy has not grown; in fact, it has declined. The economies of East Asia, including China, have a substantially higher share of manufacturing than India does. This suggests that for India the inability to grow its manufacturing, potentially the most dynamic sector of an economy, may have had a role in keeping its per capita income low, and thus poverty high.

The question to be asked is: Why is it that, despite the focused reform of the policy regime in relation to manufacturing, it has had no success in raising the share of manufacturing in the economy? I can think of four factors underlying this outcome. They are based on what we can infer from the experience of East Asia, which is a meaningful thing to do as these are Asian economies which were not much richer than India in the 1950s. Of these, two factors are economic and two are rooted in political economy.

Superior level of schooling

Perhaps the most important point is the superior level of schooling in societies to the east of India.

Let us for a moment ignore the much-cited examples of Korea and Taiwan and look at economies closer to India, both culturally and in terms of per capita income, when they started out.

In this connection, this observation is pertinent: “The proportion of the population that was illiterate in India in 2004 was similar to that observed around 1970 in China or 1960 in Malaysia. The fraction of the population that had completed secondary education in India in 2004 (16 per cent) is half of the figure that had prevailed in China in 1975.”

These numbers show the staggering gap between India and her eastern neighbours in terms of education levels.

In the twenty-first century, literacy can hardly be a sufficient qualification for a member of a globally exposed manufacturing sector. So, even if India may have made strides in making its population literate, it would have remained backward in terms of the skill level of its population well after the liberalising reforms of 1991, for little has been done on this front until very recently.

It does not take much to infer that India's manufacturers would have difficulty competing globally while employing a labour force that has had less schooling and possesses less skills than the workers of the rest of the world.

The second economic factor in the East Asian success in manufacturing is the availability of infrastructure.

Infrastructure is not easy to measure, as implied in Pierro Sraffa's quip “How many tonnes is a tunnel?”

But we are able to gather from the time taken to travel from Beijing to Shanghai, and the quick turnaround possible for container ships in Singapore, to assess the infrastructural prowess in the East compared to India.

An aspect of this is that, at least in China, the infrastructure has been built by the state.

Interestingly, unlike in the Nehru–Mahalanobis Strategy, as implied by the allocation of public investment, in the economic reforms of 1991 there seems to have been no real appreciation of where the infrastructure needed for the faster growth imagined would come from.

As has been conveyed already, these reforms were largely in the nature of the liberalisation. That infrastructure is important, and that much of it would have to be provided by government, is apparent from the phase when India’s economy grew at its fastest ever—the five years from 2003. This was a period of very high public investment in infrastructure.

Of course, private investment grew too, but public investment grew faster. This brief phase was one of the few when a growth transition was dominated by manufacturing, i.e. it was the increase in the rate of growth of manufacturing that contributed most to the rise in the growth rate of the economy. It points strongly to the importance of public provision of infrastructure for the growth of manufacturing.

Role of bureaucracy

Finally, the third and the fourth factors both relate to political economy.

These refer to the role of the bureaucracy and the capacity of vested interests to undermine the growth orientation of the state. As may be seen, they actually go together.

Political economy explanations of the East Asian miracle see it as having been engineered by a bureaucratic, authoritarian industrialising regime (bair).

The economist Robert Wade has attributed to the East Asian state the achievement of “governing the market”, but it is important to appreciate that the state also succeeded in governing the bureaucracy to the extent that the latter had to play a supportive role in the industrialisation process.

This may have been altogether different from the Indian experience as identified by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi very early in his tenure (as discussed in the previous chapter).

In India the bureaucracy has remained relatively ungoverned, thanks to colonial-era rules that have enshrined their independence.

Apart from the bureaucracy, India has experienced the role of vested interests in the form of rich farmers, industrial capitalists, and a small but militant labour force in the organised sector of the economy.

At various times India’s governments have bent to these interests, thus sacrificing growth opportunities.

At least in the early days of industrialisation in East Asia, the fact that they were dictatorships meant that economic vested interests such as the ones described above were virtually non-existent.

But even the taming of vested interests and the disciplining of the bureaucracy would not have sufficed to produce the East Asian miracle, which was underpinned by intelligent policy design and the public provision of infrastructure and education on a significant scale. The latter was largely absent in India.

To see the East Asian experience of growth and development entirely in terms of free markets and openness to trade would be to completely misread it.

As a meta narrative it may be said the it is human development that underlies the rise of these countries. They created a healthy and educated population, which constitutes the sinews of the economy. India can learn from this history.

By comparison with East Asia, India’s bureaucracy has been left relatively ungoverned. The consequences of this were clearly understood by Rajiv Gandhi, as I showed in the last chapter, but he did not live to possibly make a difference to this arrangement.

An independent bureaucracy that can slide into unaccountability reflects the governance model during colonial rule in India, starting with the East India Company.

In an insightful commentary on his compatriots, Adam Smith observed that their only concern was to build a fortune by any means and to get out of the country as fast as possible, no matter what the consequences for its inhabitants.

However, even this understanding of the rationale of colonialism is not enough to appreciate its debilitating consequences for India.

To hold India, the British invented an intermediary class standing between themselves and the “natives”–as they saw Indians. That class was the bureaucracy and for Indians there was no redress against its depredations. The colonial regime, on the other hand, tolerated its excesses as a small price to pay for retaining a remunerative colony.

Colonial apparatus

The colonial administrative apparatus has been retained intact in independent India. Of course, this was not inevitable. The Supreme Court recently asked the Government of India to state why it retains a sedition law long used to immobilise Indians during colonial times.

While many understand the absurdity of a sedition law today, the crippling effect of colonial practices that govern economic activity has gone unscrutinised.

Random inspection of a company’s premises by state functionaries sits at the pinnacle of these practices, preventing India’s industry from achieving its potential.

Economists are hard put to resolve the puzzle that the manufacturing sector has not expanded relative to the economy following the reforms. We can now see that while the elegantly crafted trade and industry reforms have addressed the policy regime, they have not addressed the conditions under which production takes place in this country, notably the need for the producer to continuously interact with an unaccountable government machinery.

This may have held back the expansion of the manufacturing sector as intended. India’s regulatory regime needs radical overhauling.

A second reason for why manufacturing did not grow relative to the economy, despite it being the focus of the reforms, is very likely the slow growth of demand.

The reforms themselves had focused on the supply side. Above, it was argued that demand would have to grow for some part of the Indian population to move out of agriculture into the non-agricultural sectors of the economy. But the reforms did not include a mechanism by which demand would expand.

Interestingly enough, at a time when the economics of growth was far less well understood by the profession, the Nehru–Mahalanobis Strategy had already accounted for demand growth. The external source of demand identified by Mahalanobis was public investment.

It is worth noting that the share of manufacturing in the economy did grow during the Nehru era. In trying to understand from the demand side the factors underlying the stagnant share of manufacturing after 1991, the following development may hold a clue.

The very improvement in the quality and diversity of goods produced with the manufacturing sector not registering significantly higher rates of growth on a sustained basis may be a reflection of growing inequality.

The demand for superior goods could be coming from the section of the population that is doing better out of growth.

If growth is unequalising, the demand for goods of mass consumption is unlikely to grow fast.

Piketty and Chancel have provided evidence of sharply rising inequality in India after 1991. In fact, after having declined for about a quarter of a century, inequality began to grow again in the 1980s.

Both the absolute level of inequality and its trend are quite staggering.

The share of the top one percent of the population was only six percent in the early 1980s but rose to 22 percent in 2015. It is plausible that worsening distribution smothered the growth of demand.

The rich are perhaps more likely to spend on high-end real estate than manufactures. Moreover, some part of their demand may be diverted to imports, even when they are manufactured goods.

The Piketty–Chancel estimates have been contested, however, and the relationship between growing inequality and the growth of manufacturing remains to be fully worked out.

Conclusion: Returning to the World Unprepared

An economic assessment of the development of India’s economy since 1991 would read as follows. There has been an acceleration of economic growth accompanied by a widening of the range of consumer goods produced and improvement in the quality of services available.

Furthermore, the economy has passed the longest period since 1947 without facing balance-of-payments stress. However, not all sectors of the economy have shown the same dynamism, with the performance of agriculture actually becoming a cause for concern.

One aspect of this uneven growth has been an unequal distribution of opportunity within the economy.

This unevenness has left a significant section of the population with a low income, even though the extreme poverty that is captured by India’s official poverty line has continued to decline.

Studies of the economic history of the country since 1991 tend to drown in the minutae of economic policy changes, obscuring the essence of the reforms which was to re-integrate India with the rest of the world. Long before discussions of the possibility of India becoming a Great Power had arisen–in fact even before the Common Era–India was a great trading nation.

Its goods–one could even say “services” if Buddhist missionaries who had travelled eastward are included–were prized in the countries to which they found their way. This character of India’s economy altered significantly after 1947.

The shift may be considered a failing of the economic policy of that time, even if on balance that policy was far more successful than acknowledged, as I have shown in Chapter 1.

It is not possible to be a significant player on the global economic stage and remain protectionist. India has since recognised this and undertaken the steps necessary to make a return to where it belonged in the distant past. Though the economic reforms of 1991 have had some successes, as recounted here, they are yet to establish the country as a successful world trader.

Indeed, after thirty years we can see that liberalisation is a necessary but not sufficient condition for this to be achieved. An educated workforce with globally comparable skills, world class infrastructure, and an enabling government machinery are necessary for a country to hold its own in the world market.

(The author, Pulapre Balakrishnan, is Professor of Economics, Ashoka University. This book has been published by Permanent Black in association with Ashoka University. An extract has been published here with the permission of the publisher)

Check out the book on Amazon

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.