Parvathi Benu

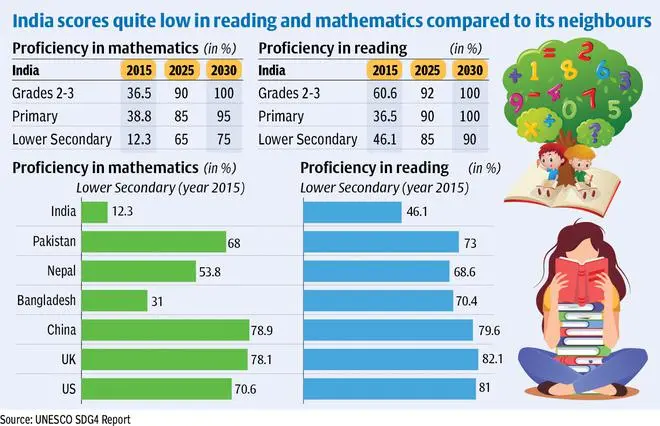

Only 12.3 per cent of India’s lower secondary school students (aged 10–16) are proficient in basic mathematics, according to the Unesco’s SDG 4 report, which was released on January 24.

The report says that while India projects that 65 per cent of its lower secondary graduates will have minimum mathematics proficiency by 2025 and 75 per cent by 2030, its current figure is far lower than that of many of its neighbours, including Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal. In 2015, 68 per cent of Pakistan’s lower secondary students showed minimum mathematical proficiency, 50.6 per cent in Sri Lanka, 53.8 per cent in Nepal and 31 per cent in Bangladesh. It is as high as 79.6, 70.6 and 78.1 per cent in developed nations like China, the US and UK, respectively.

Related Stories

Online education has created problems beyond the digital divide for school children

Beyond just the digital divide, schoolchildren forced to go online are battling screen fatigue, distractions at home, and loss of social skillsRelated Stories

'3 idiots' fame school yet to get CBSE affiliation after over two decades since its inception

The school is presently affiliated to Jammu and Kashmir State Board of School EducationRelated Stories

Has India lost its demographic sweet spot?

In the developed world this caused economic growth to fall. India needs to act now to avoid a similar fateRelated Stories

Hybrid learning is welcomed by students, teachers in major cities: report

However, limited social interaction is a major challenge in online learning methodWhile the figure for India has taken its academia by surprise, Manos Antoninis, Director of Unesco’s Global Education Monitoring Report, says the value was calculated by linking the results of the National Achievement Survey at grade 8 in 2017 to the global minimum level of proficiency. The survey — which evaluated students of grades 3, 5 and 8 across the country — found that only 39.5 per cent in grade 8 were proficient in mathematics. This includes the 10.5 per cent who displayed advanced skills.

At the same time, Antoninis said, “it is important to avoid a shallow interpretation of such a statistic. It is not the result of one or other government to improve education. It is a national endeavour that requires all efforts, from public authorities at all levels, schools, teachers, families and students”.

Noting that India’s projections were not overambitious, Antoninis said, “The big challenge for India is to improve what children learn while in school, especially in primary and middle schools. It is, therefore, important that the National Education Policy 2020 has put this item at the top of the agenda.”

R Ramanujam, a former professor of The Institute of Mathematical Sciences, found the low number rather surprising. “The number seems quite puzzling. From where did they get this data? The fact that our achievement levels are abysmally low is definitely indicated by all studies. While one does expect a progressively lower figure as we go up, such a drop seems surprising,” he said.

On what India could do to make its students more proficient in mathematics, Ramanujam said the need was for more effort, right from lower grades, to provide a strong foundation. “The lower proficiency in mathematics as students graduate to higher grades is universal. At primary levels, we are not ensuring universal achievement. This has to be changed,” he said.

The Unesco report noted that most countries will not achieve the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDG) — quality education is one of them — by 2030. “For many countries, COVID-19 is expected to slow down or even reverse their educational progress,” says the report. At the same time, it adds, “While SDG 4 is unlikely to be achieved by 2030, according to countries’ own estimations, facing up to this reality by no means dilutes the agenda.”

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.