In the 75th year of India’s independence, much can be written about how economic reforms have unlocked the true potential of the somnolent Indian economy and lifted the income levels and living standards of ordinary folk. But a less-talked-about offshoot of this prosperity has been the revolution that has swept India’s savings and investment landscape.

In the last 30 years, the attitude of the Indian saver towards risk and return has changed dramatically, even as the savings and investment opportunities available to her/him have grown by leaps and bounds. Here’s tracing this revolution.

Advantage, financial assets

From anaemic levels of about 9 per cent of GDP in the fifties, India’s gross savings rate has vaulted to over 30 per cent of GDP in recent years. These savings represent sums put away by both individuals and institutions, the latter in both public and private sectors. While savings by the public sector have been declining in recent years, both households and the private corporate sector have raised their contributions.

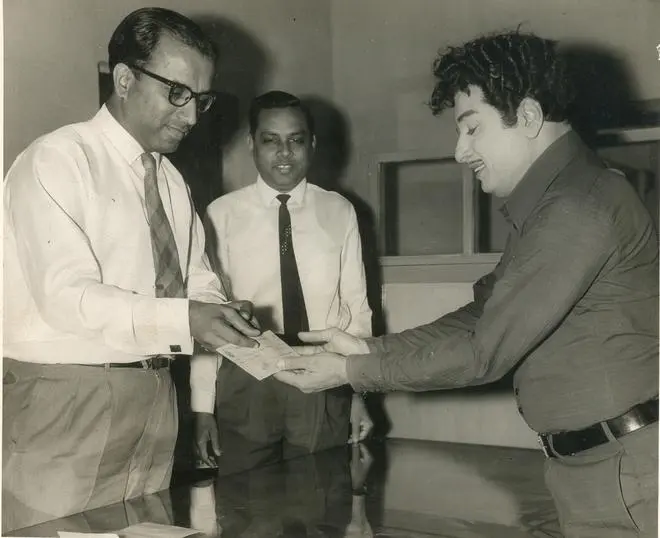

A General Manager of Glaxo Laboratory, is seen handing over a cheque for Rs. 2 lakhs for investment in small savings to M.G. Ramachandran, Vice-Chairman, State Small Savings Advisory Board on December 9, 1970, at Satya Studios, Madras. PHOTO: THE HINDU ARCHIVES | Photo Credit: DIPR

Traditionally, Indian retail savers put their faith in hard assets that they could see and keep behind lock and key, with 77 per cent of the average household’s assets parked in real estate (mainly a self-occupied home or farm land) and 11 per cent in gold, with only a 5 per cent allocation to financial assets, as per the Indian Household Finance Report brought out in 2017. But the last five years have seen a material shift in preferences towards financial assets, with Covid giving financial assets a particularly big lift. RBI data as of March 2020 showed that of roughly ₹64-lakh crore gross savings generated in FY20, households chipped in with nearly ₹40 lakh crore. Of this, physical assets and financial assets commanded similar allocations of about ₹23 lakh crore, with gold and silver getting about ₹43,000 crore.

In the 1980s, Indian households were adding a mere ₹10,000-20,000 crore annually to their financial assets. By the early nineties, with liberalisation opening up new jobs and opportunities, this grew to over ₹1-lakh crore a year. This sum doubled in the nineties and by 2020, had expanded to over ₹22- lakh crore. This shift has put a significant savings pool at the disposal of Indian financial sector players- be it banks, insurance companies, mutual funds, the behemoth LIC, corporate issuers of bonds and equities or new-fangled fintech platforms. India’s financial market regulators now have their hands full framing regulations for this ever-growing set of actors.

Pandit Pant, Union Home Minister inaugurates the new Postal Gift Coupon Scheme to popularise small savings in New Delhi on July 1, purchasing the first coupon from Mr. Lal Bahadur Shastri, Union Minister for Transport at the counter.

From avoiding risk, to embracing it

For Indian savers who avoided ‘paper’ assets such as stocks and mutual funds in favour of precious metals and real estate until a decade ago, the onset of Covid brought about a material shift in preferences. During the pandemic, with lockdowns and health emergencies hitting, households made a big shift in favour of bank deposits, which could be seamlessly transmitted and liquidated at short notice. Indian banks, sitting on a deposit base of about ₹110-lakh crore in 2017-18 saw this surge to ₹151-lakh crore by 2020-21, as savers shored up their nest-eggs.

But even as interest rates on bank deposits were plumbing new depths during Covid and after, equities were charting a breath-taking ascent, fanning FOMO (Fear of missing out). As the stock markets rebounded sharply between March 2020 and October 2021, both newbie investors and older ones earning measly returns in debt, were drawn into stocks, mutual fund SIPs, curated portfolios such as smallcases and even derivatives trading for their vastly better returns. The widespread use of technology to onboard investors quickly and easily without paperwork and the ease of transacting through mobile apps and platforms, have given this trend wings.

AN INVESTOR FILLS OUT A REPURCHASE FORM AT THE OFFICE OF INDIA’S LARGEST MUTUAL FUND MANAGER, THE UNIT TRUST OF INDIA, AUGUST 1, 2001, AFTER THE FUND RESUMED REDEMPTIONS IN ITS FLAGSHIP SCHEME, US-64. | Photo Credit: SAVITA KIRLOSKAR

Surge in demat accounts

The number of demat accounts opened in the Indian markets has trebled in the last three years, now nudging the 10 crore mark. Assets managed by MFs have doubled in the five years to FY22, to over ₹38 lakh crore now. This influx of domestic money has allowed Indian stock markets to weather recent FPI outflows and global upheavals much better than peers. Covid has also given a much-needed leg up to term insurance and health insurance providers with Indians realising that their financial plans are incomplete without an emergency fund and risk covers.

It is early days yet to assess if the Indian investors’ newfound affinity for equities and MFs is simply a case of their being taken in by recent returns or reflects a realisation that market-linked avenues such as equities and MFs can deliver inflation-beating returns in the long run. Hopefully, this trend in here to stay, as recent market corrections have not prompted any panic moves out of equities or MFs.

Unregulated avenues

Vigilant as Indian regulators have been in ensuring that banks, NBFCs, MFs and insurers under their watch play by the rules, every boom phase in India has also brought with it, a large contingent of unregulated players who have managed to woo investors with their get-rich-quick schemes.

If it was unregistered NBFCs and chit funds who made away with the savings of South Indian households in the early eighties and nineties, orchard, teak and emu-rearing schemes were the flavour of the season in the early 2000s. These schemes have inevitably been backed by promotional blitzes and celebrity endorsements. With the internet opening the eyes of Indian investors to unregulated assets on a global scale, in the recent boom, they have been persuaded to invest in newfangled assets such as cryptocurrencies, Non-Fungible Tokens, DeFi tokens et al in the recent boom. After a meteoric rise backed by speculative interest, these ‘assets’ - which are without any underlying - have crashed recently. Global governments, after cautioning investors on the dangers of cryptos have been so far been sitting on the fence, curiously reluctant to act on banning or even regulating them.

Should recent losses made by crypto or NFT investors prove permanent, it would only reinforce the oldest investing lesson that every seasoned saver has learnt the hard way. There’s no easy money in the financial markets. High returns always come with the risk of losing your shirt.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.