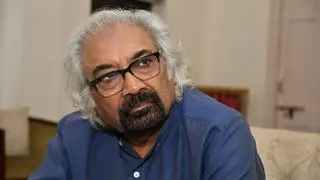

“Mental health intervention should be a part of disaster management planning of all countries,” says Shekhar Saxena, Professor of the Practice of Global Mental Health at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. In an interaction with BusinessLine , the former Director of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse at WHO (2010-18) highlights about the importance of governments having to tackle public mental health at a time of the global Covid-19 pandemic, when the countries need to be brought back on track again. Edited excerpts:

The world is focussing on the fight to save itself from the coronavirus. But do you also see a concomitant mental health pandemic in the making?

Humankind has of course experienced epidemics and pandemics for as long as history can be remembered. In earlier pandemics, there has been shocking loss of life. Today, too, so many get infected and die. Equally, so many get infected and live — and for them there are new realities to cope with; that can mean severe psychological stress. It is only recently that we have come to realise just how massive and widespread the mental health and well-being impact of a disaster can be. While everyone can understand that the stress of being in the midst of a pandemic can be painful, the cumulative impact of events and situations can actually be very large. In fact, many believe that it can be larger than the impact of the infection itself.

How exactly does this pandemic affect public mental health?

One can look at this in three ways. First is the psychological impact, which comes from fear and uncertainty. These are rampant during this pandemic. There are so many reasons to be afraid: fear of getting infected, fear of dying, the idea that the illness could strike one’s own country or city or family. The other factor is that of loss, which is very prevalent during the current pandemic. There are so many things we lose: our freedom to do what we want, our jobs, perhaps, our financial security, loss of human interaction and touch, and even the loss of a loved one in some cases. There is also the loss of our usual pleasures in life, the lack of which leaves us more distressed. Many of our habits are also disrupted, and without those, there is a persistent feeling of something missing. Socialising, going out, meeting people, are all things that happen very regularly but are now just gone.

All this gives rise to a feeling of hopelessness and helplessness, which are actually characteristic signs of depression. Now, not everyone will have anxiety and depression as an illness, but almost all of us will have stress and distress; and in some cases, it will be symptomatic and even evolve into a disorder. When it gets to that point, it means it impairs normal functioning and symptoms that become so severe and last so long that it requires help. These are all points along a mental health spectrum ranging from very mentally healthy and resilient to incapacitated and needing intervention.

Imagine also how anxiety and depression would shape up in those people who are perhaps stranded somewhere, with no help or support system, and perhaps even having to scramble for the basic necessities of life like food and shelter. We have already seen this among migrant workers who are trying to rush to the only secure spaces they know, their homes. Stress can also be extreme for those who have someone in the family who is ill or even dying; this is a terrible thing to deal with at any time, but during the pandemic there is the added issue of not being able to help. Those who are in isolation are also unsurprisingly stressed — their loved ones can’t visit them.

Would you say that there is a long-term impact of these stressful events?

Human beings are remarkably resilient, hence much of the psychological fallout may be short-term. But certainly, it can also be long-term as people de-compensate, and this turns into problems like persistent anxiety or depression or post traumatic stress disorder, a well-known entity. A major factor for this continued mental health problems will be the continued economic and social impact of the pandemic, which will result in prolonged anxiety and depression and even a higher rate of suicides. Let us not forget that India is responsible for one-third of all suicidal deaths in the world. It will take countries and communities not months but years to recoup the losses they have suffered.

Do you believe that the effect of the pandemic on mental health will be as bad as for wars and other similar situations?

All population-level disasters have similar fallouts, whether it’s a man-made disaster like a war or a natural one like a tsunami or an earthquake. The human reaction to these is very similar because the common elements are the same — fear, uncertainty and loss. Recent studies have demonstrated that one in five persons living in these situations has a diagnosable mental disorder. Imagine that in some parts of the world, both conflict and pandemic are happening at the same time. The psychological impact of this will be enormous.

How aware are governments all over the world of the mental health dimension of the pandemic?

Mental health issues have always been somewhat invisible and poorly understood, and governments and populations are ill-prepared to address the on-coming impact of this type of disaster. Mental health systems have always been very scanty in India and during this time, the gap between what is needed and what is available has widened markedly. That is actually one of the reasons why the impact will be larger, because the needs are increasing and supply decreasing because of difficulties in access. Policymakers all over the world are becoming more aware of the mental health impact of the pandemic, but this awareness is not getting translated into action which requires investments.

What should governments do, to prevent or at least lessen the mental health fallout at a wider level?

Governments should work together with relevant stakeholders to strengthen the mental healthcare system. WHO has given guidance to governments on the mental health aspects of Covid-19, and even before this pandemic, epidemiologists and other experts have warned of the need to be prepared. Yet, the global transmission of the disease has been so unexpectedly rapid that it has quickly overwhelmed the healthcare systems of many countries. In this scenario, the mental health dimension has been a lower priority consideration. Mental health intervention should be a part of the disaster management planning of all countries. It’s there on paper, but forgotten when implementation of the management begins.

From the earliest period it should be kept in mind especially while communicating to the public. Clear and unambiguous messages and advice are very important. And mental health consequences of policies such as the lockdown in the current pandemic, should be anticipated and planned for. Access to psychosocial resources has to be increased especially for vulnerable populations. Steps have to be taken to curb the ‘infodemic’ because misinformation only increases anxiety everywhere.

Do governments not have to think beyond the pandemic to the time when the public needs the mental strength to reset life and bring it back to normal?

Some of the mental health consequences of the pandemic will decrease the probability that people will make their best attempts to help an economic and social recovery. As countries try to recover, the public will need to enhance efforts to return to normal, and so governments need to empower civil society to provide the assistance that they can provide. This should be one of the major components of any disaster recovery plan. Access to mental health services must be increased, but that does not necessarily mean more psychiatrists and psychologists. Trained lay counsellors can be very helpful, as can be self-help groups. With a small amount of guidance, people can look after themselves and each other much better because of the mutual support they can provide and receive. These kind of psycho-social interventions are actually happening everywhere but the government can support them.

In India, some of the NGOs are organising these groups and using very simple techniques using online methods to connect large populations. Employers, too, play a very important role here by staying in touch with their employees and decrease the financial distress and feelings of uncertainty. As we begin to come out of the shadow of the pandemic, we need to think more about what internal resources we have been able to use during these difficult times rather than what we have lost in the process.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.