Customs duties regulate India’s merchandise imports, which stand at around $700 billion — a fifth of our GDP. Naturally, they remain a major industrial and trade policy tool for India. While the government may announce duty changes at any time, the Union Budget is the time for significant changes. What Customs duty changes will prepare India best to brace the challenging global environment?

To the economists’ dismay, big bang duty cuts are out of flavour globally. Nations have turned inwards. No country plans to reduce trade barriers, including Customs duties. The countries are increasing barriers to entry.

The US is implementing Production Linked Incentive-type programmes, giving about $500 billion in subsidies and increasing tariffs. Obtaining minimum local value addition in the US is a precondition to getting a subsidy. India could not impose such conditions in its PLI schemes even though it was critical to rule out superficial manufacturing, as it was WTO incompatible.

Here are five simple actions to turn Customs duties into tools for strengthening Make in India.

One, freeze import duties: India should announce a five-year duty freeze. Any change may upset many PLI/PMP and other manufacturing programmes. The government must reduce import duties only when a clear economic case is present.

The five-year duty freeze should be co-terminus with five years of the PLI scheme. The duty freeze will also convey the message of policy stability.

Steep and sudden reductions in import duties in the mid-1990s forced most small and medium firms in pharma, electronics, chemicals, dyes, and toy product groups to shut operations. Many manufacturers became traders for goods from China.

Two, retain import duty on components: Import duty on components will promote deep manufacturing. All electronic and complex engineering devices consist of thousands of components. India will become a true manufacturer of electronics and telecom devices only when components are manufactured here. But if the duty on components is zero, they will be imported, resulting in the simple assembly of final products in India. Most firms that do this will disappear when incentives end. There have been several such cases in the past.

For instance, during 2015-17, many firms started assembling smartphones by importing components and SKD kits. Tax arbitrage provided this opportunity. To promote manufacturing, the government announced a differential tax policy. Import of components to manufacture phones attracted only one per cent countervailing duty. But importing for sale attracted a 12.5 per cent duty.

The arbitrage disappeared with the introduction of GST in July 2017. All such firms disappeared simultaneously. The annual loss to the government was ₹5,000 crore on the ₹40,000 crore domestic turnover. The ventures created low-paying, 40,000 more jobs. Each job cost the government over ₹12 lakh annually.

Three, create duty arbitrage: India has thousands of good-quality manufacturers in engineering and other sectors. Support such sectors through the creation of duty arbitrage between input and output. Also, introduce technical regulations, quality control orders, and compulsory registration orders. This will ensure quality production and check substandard imports.

Four, remove inverted duty conditions from important product groups: An inverted duty structure (IDS) is a situation where the import duty on finished goods is lower than the import duty on intermediate products or raw materials. Duty inversion could also exist because of IGST, anti-dumping and CVD duties.

Determining ERP

The problem is we cannot determine IDS by just looking at the duty rates on output and input. One needs to determine the effective rate of protection (ERP), which is defined as the percentage excess of domestic value added created because of the imposition of tariffs and non-tariff barriers. Calculations take into account the (i) share of imported inputs used in production; and (ii) effect of tariff paid on the domestic value add.

The Tariff Commission did the best work in India on IDS, having published many detailed studies.

An industry may not be affected if ERP remains positive despite IDS because the tariff structure still protects it. But the government may consider changes if ERP for a sector is negative due to IDS. It is crucial to establish a link between IDS and ERP. FTAs (free trade agreements) have multiplied the number of IDS cases. We must create a mechanism to look at each case, as IDS has the potential to destroy the entire product sector.

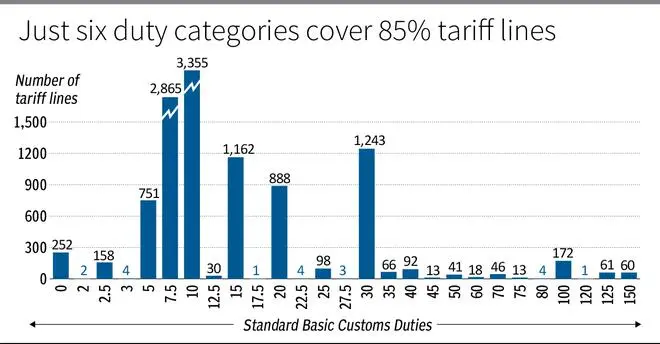

Five, reduce duty slabs to avoid confusion and minimise litigation: We have more than 26 rates for Customs duties ranging from zero to 150 per cent. The 26 duty rates are 0, 2, 2.5, 3, 5,7.5, 10, 12.5, 17.5, 20, 22.5, 25,27.5, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 60, 70, 75, 80, 100, 120, 125, and 150. In addition, there are over 100 specific or mixed-duty slabs.

More duty slabs result in different duties for similar items, leading to classification disputes and expensive litigation. This also makes the automated processing of documents difficult. The money involved due to misclassification could be significant, considering the enormous value of India’s imports.

The government must compress the duty rates to five. Doing this may not be complex. Already 85 per cent of tariff lines are covered under six duty categories. These are 5 per cent, 7.5 per cent, 10 per cent, 15 per cent, 20 per cent, and 30 per cent. A beginning may be made for industrial products.

Reduction in the number of duty slabs will immediately enhance the system’s transparency, reduce classification disputes, and allow for machine processing of documents.

The government has the flexibility to ignore the revenue angle while making decisions. Customs duties contribute to less than 8 per cent of gross tax revenue.

The writer is co-founder of Global Trade Research Initiative, an economic think tank

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.