Many central banks feel that peak inflation is behind us. Pressures are building up on several central banks to go slow in hiking their policy rates. The magnitude of rate hikes has been trimmed in many jurisdictions as cumulative rate hikes so far would take time to fully impact the economies.

A significant slowdown of the global economy is also predicted by many economists and multilateral institutions like the IMF and the World Bank. Global uncertainties due to price rise and geopolitical risks, although alive, have subsided. The surge in Covid infections in some parts of the world, especially China, is unlikely to create pandemic-like havoc as most people are vaccinated and countries have developed capabilities to handle the situation.

Against this backdrop, it is time to evaluate whether the fight against inflation is over. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC), policy rates in many central banks, particularly in developed countries, were at zero lower bound. Globally, normalisation of the monetary policy up to when the pandemic struck was incomplete.

In the wake of the pandemic, many central banks quickly reverted to zero policy rates to protect their economies from the biggest catastrophe of the century. The recent policy rate hikes in most parts of the world were rapid and large. Nevertheless, very few central banks have reached neutral policy rates, let alone tight monetary policy.

Fighting inflation by policy normalisation alone is not sufficient unless unprecedented excess liquidity, released by almost all central banks during the Covid crisis, is clawed back. While it is easy to pump excess liquidity quickly, non-disruptive withdrawal of excess liquidity takes time, particularly when the world economy is used to excess liquidity after the GFC.

Retail inflation remains well above the target in many countries despite some moderation. Hence, it is too early to give a sense of comfort to policymakers to abandon the fight against inflation. Due to the large front-loading done so far, there may be a case for calibrated policy rate hikes depending on the situation, but dropping the guard against inflation at this stage appears premature and may be costly going forward.

In negative zone

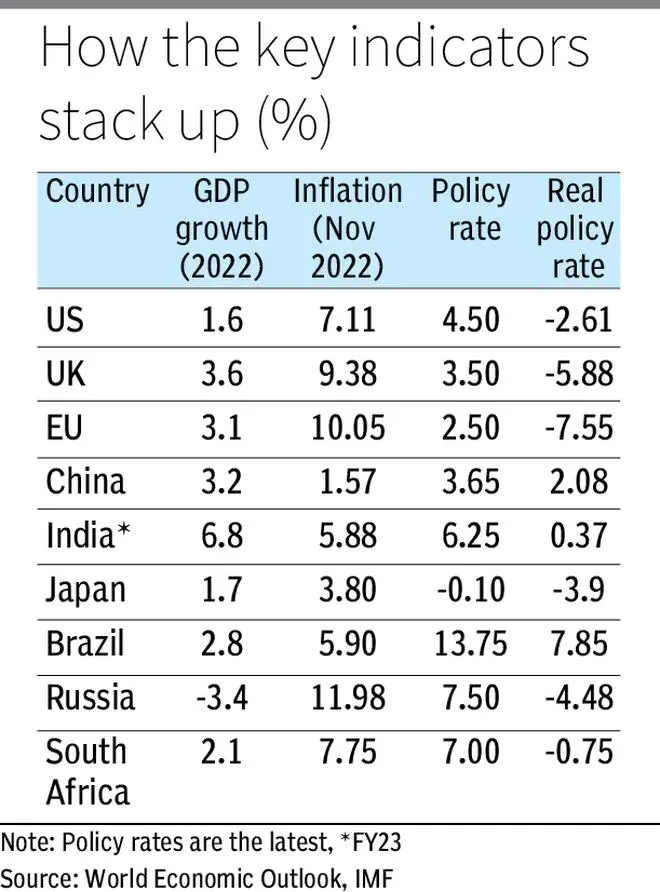

The real policy rates are currently in negative zone in many systemically important countries (Table 1).

The rate hikes in the European Union, the UK, and the US are yet to reach their peak. Japan is unlikely to remain accommodative for a longer period as retail inflation, at 3.8 per cent in November 2022, was at a four-decade high. Moreover, core inflation, excluding food and energy prices, remains stubbornly high in many countries. The supply chain disruptions have not been fully restored in the post-Covid period.

Policymakers would face serious policy challenges in 2023 as the probability of a growth slowdown/recession has increased. Inflation is unlikely to revert to its target in most parts of the world soon. Tolerating higher inflation for a long time may not be a good policy option as it harms growth above a threshold that varies from country to country.

Expecting monetary policy to support growth with high inflation has always been a policy mistake in the past. The growth-inflation trade-off is neither positive at a high rate of inflation nor is the sacrifice of growth too large in such a situation. Post-Covid, central banks should return to rule-based monetary policy at the earliest.

In India, the expected GDP growth of 6.8 per cent in FY23 is the highest among the major economies and is expected to maintain its status in FY24 as well. The softening of retail inflation to 5.9 per cent in November appears seasonal and is modest compared to the maximum tolerable limit of 6 per cent. The average CPI inflation in 2022 is likely to be 6.7 per cent on top of 5.1 per cent in 2021 and 6.6 per cent in 2020.

CPI inflation in 2023 is expected to remain 5-6 per cent, well above the target of 4 per cent.

The core inflation in India remains around 6 per cent, so dropping the inflation fight at this stage is not desirable. The real policy rate became decimally positive in December.

Although the RBI is first approaching the neutral policy rate, the rule-based neutral policy rate would be 6.5-7 per cent assuming average inflation around 5 per cent in FY24 and growth around its dented potential, say 6.5 per cent. Although, recently, members of the Monetary Policy Committee were divided on stance and policy rate hikes, it may not be prudent to abandon the inflation fight before a neutral policy rate is reached.

The writer is currently RBI Chair Professor at Utkal University and former Head of the Monetary Policy Department, RBI

b

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.