There is now a consensus on India emerging as the second fastest growing economy for the second successive year in FY24, despite the slowdown in the West.

Does this mean that India’s growth path is largely decoupled from the rest of the world?

When the ‘Make in India’ campaign was launched, its objective was to foster export promotion. Import substitution, too, was an implicit goal. Now the PLI scheme gives outright subsidies to around 14 sectors for making a certain quantum of investment that is linked with incremental output that would finally be rewarded with a 4-6 per cent payback. This has also been a means for both import substitution and exports promotion.

The question that arises is that if we have made progress on exports, then there should be some adverse impact on growth when a part of the developed world slips into a recession. Besides, in a globalised world, there could be spillover effects in other areas, especially in foreign investment flows through both the direct and portfolio routes, which would slow down.

Further, a recession in the West would also mean that demand for Indian labour as well as computer related services would come down. These could affect our balance of payments. At the other end, ECBs and NRI deposits too will get impacted depending on the policy of interest rates, especially in the West. Rising rates in the US would make ECBs dearer and NRI deposits more attractive in local territory, which will have a negative impact on domestic funding flows.

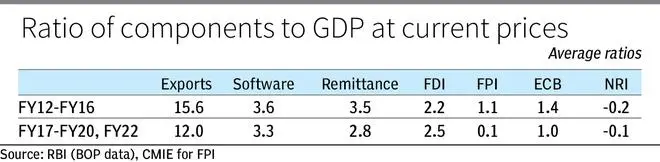

The table juxtaposes all these elements with GDP at current prices. The purpose is to see how these components have moved along with GDP in the last decade. As a component of GDP, exports boost growth, the other flows are assumed to increase as a proportion of the GDP. Normally, absolute figures of software receipts and remittances, when viewed in isolation of the GDP, do not give a true idea of how they are faring over time.

Data for the last 10 years have been considered here and the average for the last two quinquennium has been considered. The second quinquennium excludes 2020-21 and hence includes FY17-20 and FY22. The first period covers FY12-FY16.

Several interesting points emerge from this table. First, the ratio of exports to GDP has come down over time. This is both good and bad news. The good part of this story is that it shows growth is primarily driven by domestic factors and hence decline in exports does not affect GDP growth significantly. This is probably one reason why growth projections are high for next year, at 6-6.5 per cent. The not-so-good part of this story is that even though a lot of push has been given to exports with specific emphasis on sectors that have a comparative advantage, they have not quite managed to carve a niche.

Even where opportunities have arisen, such as the US putting restrictions on Chinese imports or the more recent the Ukraine war, we have not quite made any significant inroads. Hence this means that while a steady growth in exports will supplement domestic growth, we are far from being an export-led economy.

Second, while software receipts growth in rupee terms has been 56 per cent in the last five years, the GDP it has lagged and hence in relative terms has not kept pace. Quite clearly this will be an area of concern in FY24 if the recession hits the demand for these services.

Third, the fall in the ratio for remittances is also considerable, as it has declined from 3.5 per cent to 2.8 per cent. Here too growth has been just 35 per cent in rupee terms for the average remittances in the two quinquennium. The pace of growth has not been in line with the GDP growth even though it has been rising. Here too there can be an impact at the margin due to the global slowdown.

Fourth, the FDI flows have been very positive with growth of 89 per cent in rupee terms in the last five years. This is an area where there is uncertainty. The flow of FDI depends on both push and pull factors. The pull factor is strong with the economy doing well and the policy framework in place. In fact, the China factor will shift more investments towards India. However, the push factor will depend on both the quantum of investible funds available. Therefore the net impact needs to be monitored closely.

Fifth, the ratio of FPI to GDP has come down sharply due to the negative flows witnessed in three of the five years. In a way this should provide comfort; even if these flows are minimal, they will not affect our markets as the indices have ballooned notwithstanding these negative flows. Domestic institutions have provided an insulation to a large extent.

Interestingly, the net NRI deposits have been negative on an average basis in both the periods. This means that there is no reason to be dependent on them for support from the point of view of balance of payments. ECBs too have seen a decline from 1.4 per cent to 1 per cent and would not be attractive at a time when the interest rates are rising all over.

What this data shows is that India still remains a largely domestic economy which provides strength to growth. But a recession does have implications for the external sector where inflows can get dented at the margin. Cumulatively they have the potential to pressurise the rupee which will remain a variable to be monitored closely by the RBI.

The writer is Chief Economist, Bank of Baroda. Viiews are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.