India’s sustained dependency on China remains a concern. During the period FY 2002 to FY 2012, trade deficit increased from $1.1 billion to $37 billion; which then touched an all-time high of $73 billion in FY 2022.

During the initial months of the Covid-19, India announced the Aatmanirbhar Bharat scheme to reduce its import reliance, mostly on China. Such an initiative was not the first of its kind, but the renewed focus was timely, as supply chain issues were creating cracks in the economy.

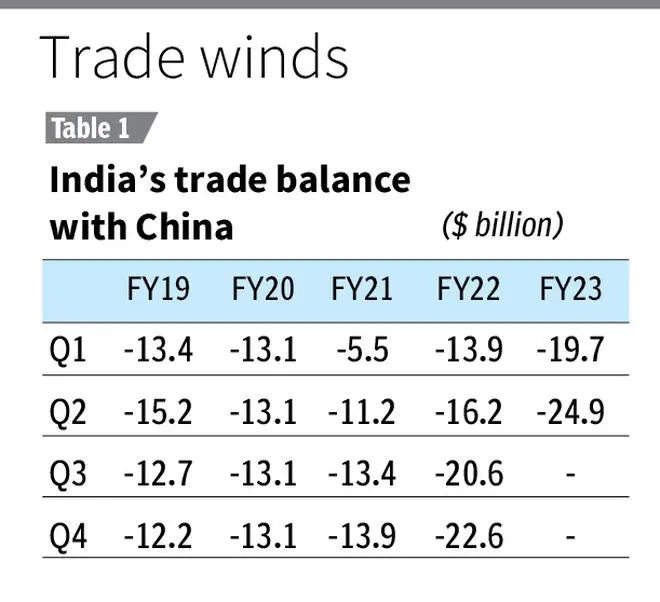

Data for the last four years show that on an average India’s quarterly trade deficit with China increased from $13.4 billion during FY 2019, to touch a peak of $18.3 billion in FY 2022. In fact, in the first two quarters of FY 2023, imports from China shot up to an average of $22.3 billion, the highest since FY 2019 (Table 1).

Product-wise, India’s top five items of imports from China also saw an increase in terms of value, from $70.3 billion in FY 2019 to $94.6 billion in FY 2022 — with electronic components seeing a significant and perennial increase.

Production Linked Incentive

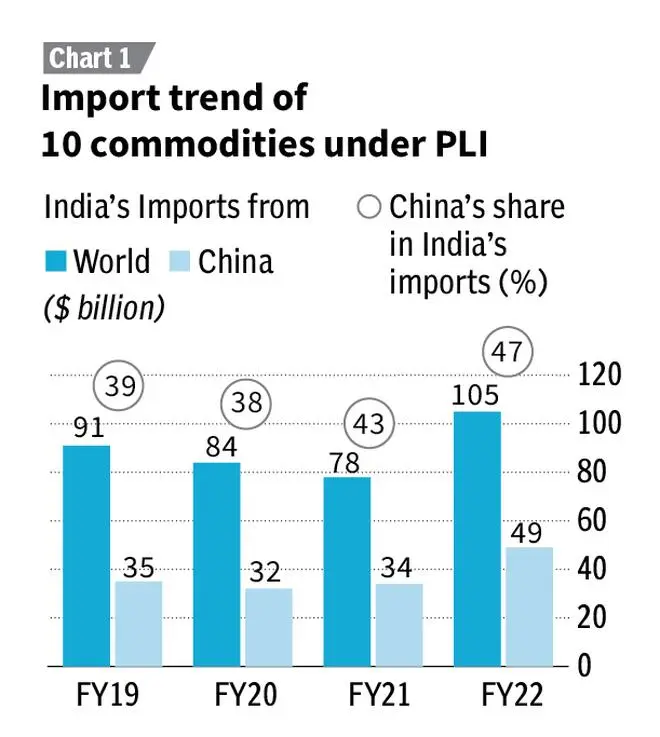

This import dependency certainly remains alarming despite India’s best efforts to reduce its imports from China. The government launched the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, covering strategically significant sectors, towards developing manufacturing capabilities in India. A lot of hope has been placed on this scheme which pans over a five-year period. As on date, there are 14 such industries which are under the PLI scheme. A harmonised code analysis of 10 of the 14 industries identified under PLI shows increasing dependency on imports from the world by India.

India’s cumulative import share of these 10 PLI sectors from China has increased in FY 2022, to touch 47 per cent; the highest in the last four years (Chart 1).

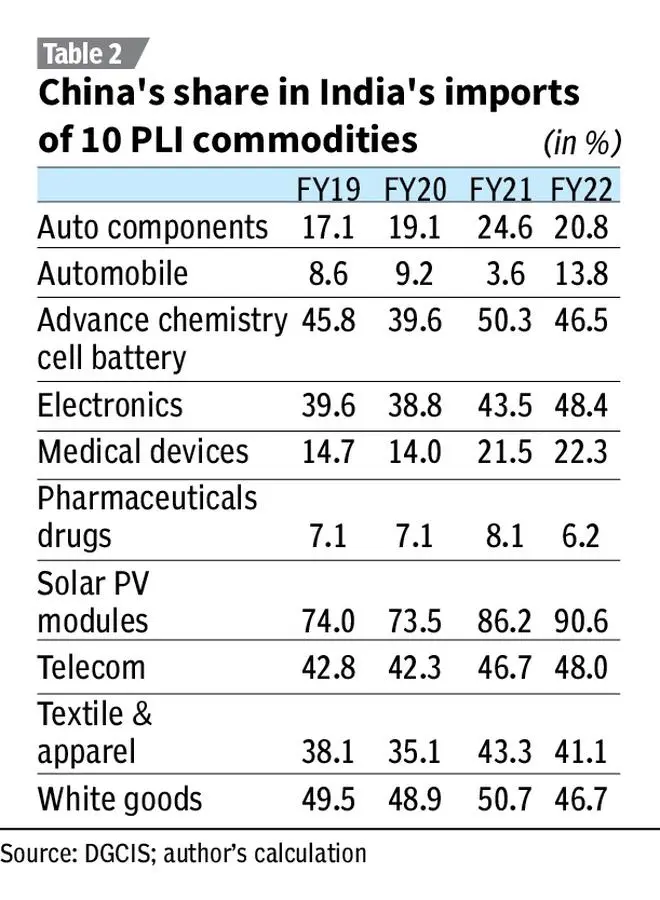

The items under the PLI scheme, which was launched in April 2020 with electronics being the first to be identified, has also witnessed an increase in their import share in the last few years, with China continuing to be the dominant source for imports (Table 2).

Holds potential

While it may be too soon and premature to conclude the impact of the PLI scheme in reducing imports from China, it holds significant potential. It could play a key role in increasing India’s share of manufacturing GDP, which has remained more or less stagnant.

However, the fact remains that in the global scheme of things, completely disregarding China is next to impossible, neither is it possible to produce all alone.

For example, India is increasingly looking at sustainable development while supporting industries like automobile and solar under PLI. However, many raw materials associated with it are imported. In this context, India needs to build strong economic ties — this may include with even with far off countries likes Chile for lithium, or South Korea for solar.

FDI will be a key factor in ensuring India reduces its import dependency. It could bring in global best practices and latest technologies, while India can offer the foreign investors a huge domestic market. If India wants to build upon the China+1 strategy, it needs to overcome the shortcomings, especially as the likes of Vietnam are attracting better investments.

Further, as PLI is an incentive-based scheme, policymakers must ensure that it succeeds even after its term ends. For example, the government should make sure accidents of the sort that occurred in Baddi in Himachal Pradesh, where a chemical leak took place in 2020, do not get replicated. This cannot help India’s efforts to emerge as a global hub.

Global supply chain disruptions caused by Covid have flagged the need for reforms. However, it is important for policymakers to take continued stock of the progress made towards minimising import dependency through its various measures. Hopefully, Union Budget 2023-24 will take care of lessening the dependency on China.

The writer is an economist with India Exim Bank. Views are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.