No tears need be shed over the government’s curbs on rice exports imposed from September 9. In fact, one should be happy that the government has learnt its lessons from the wheat conundrum the country faced in May as also the Indonesian ban on palm oil exports in April.

The question before us is: Why should India export blindly when the realisation is declining. This, particularly, when it is the top exporter making up 40 per cent of the global rice trade.

There are three facets to the restrictions. One, the government has banned exports of broken rice. Two, it has imposed a 20 per cent export duty on white (raw) rice, brown rice and paddy shipments. Three, it has exempted parboiled (boiled) and Basmati rice from any restriction.

Critics of the move say the curbs will affect supplies when demand is increasing for Indian rice in the global market, and the industry and trade have not been taken into confidence. On the other hand, there are others who feel the export duty could have been higher.

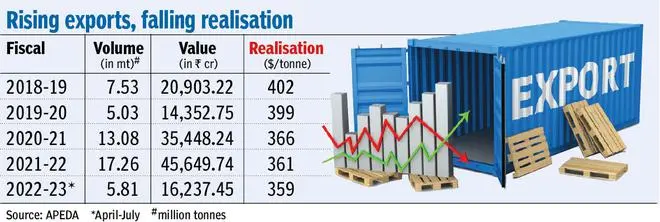

Be that as it may, the decision is timely and welcome, too, as data point to some interesting developments over the past five years. We will only look at non-basmati white rice and broken rice since Basmati shipments are not affected. Also, exports of brown rice and paddy are insignificant.

Last fiscal, India exported a record 17.26 million tonnes (mt) of non-Basmati rice with broken rice making up 3.89 mt, white rice 5.94 mt and parboiled the remaining 7.34 mt. The forex earnings were a record ₹45,700 crore. However, the per tonne realisation declined 11 per cent from $402 in 2018-19 to $359 during the April-July period of the current fiscal.

The competition among Indian traders is so cut-throat that some of them settled for margins as low as $1/tonne last year. At one point in time, Indian rice was offered at a $100/tonne discount to Thailand and Vietnam varieties. Before the curbs were announced Indian white rice was offered at discounts ranging of over $30 a tonne (Pakistan rice) to $80 (Thai rice). India’s export curbs have only helped Thailand and Vietnam raise their prices.

Lower than MSP

If the minimum support price (MSP) for paddy fixed by the government is converted, the free-on-board price is lower than the MSP. This leads to two questions. One, should Indian rice be sold at a huge discount in the global market, particularly when the government spends at least $70/tonne on paddy farmers to supply free power? Two, should the shipments be made at a price that is below the MSP?

India should not export its rice cheap. On parboiled rice, despite India’s competitors being Thailand and Pakistan, the cereal is offered at discount.

The case of broken rice exports is curiouser. According to the US Department of Agriculture, its trade increased by over 50 per cent to 6.7 mt in 2021. India’s share in this was a significant 3.89 mt. The trade was 4.8 mt in the first half of this year.

Last year, the biggest buyers of Indian broken rice were China, Vietnam and Senegal. The African country uses broken rice for one of its staple dishes, though its purchases from India have fallen. China and Vietnam buy it for making noodles and wine as also for animal feed.

On the other hand, demand for broken rice has increased within the country of late for poultry feed with corn and soyameal turning pricier, and also being diverted for ethanol manufacture.

China turned a big buyer of Indian broken rice only in 2020. Until then, it had imported hardly 1,000 tonnes. While last fiscal it imported 1.63 mt of rice with broken rice making up 96 per cent of it, this fiscal it has already bought 1.07 mt during the first four months.

The Centre is justified in taking a decision to ensure broken rice is available for its own poultry and other user industries than meet Chinese animal feed demand. The move is also timely since the government has anticipated more demand for it in view of the 75-day heat wave in China and the brewing supply crisis in the global rice market.

There are a couple of other interesting aspects to the government’s decision, especially in making a distinction between countries in the East and the West.

Exports of Basmati and parboiled rice to the West have been spared since the Gulf nations and poor African countries, respectively, are the major buyers. The move ensures it does not rub the Gulf nations on the wrong side and invite criticism for putting at risk the African countries’ food security.

Shipments of non-Basmati white and broken rice, which are to the nations in the East, have been curbed. Indonesia, Vietnam and China are likely to be affected. These countries depend on cheaper Indian rice mainly for feed purposes and the Centre’s indirect message is to import corn from us. That way growers will stand to benefit with corn prices ruling at ₹22,000-23,000 a tonne.

There need not be any concern over paddy growers getting the MSP when harvest begins in the next few weeks. The Centre has fixed an ambitious rice procurement target of 51.8 mt for its central pool. Going by the wheat experience, particularly in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, it is likely the growers will want more than the MSP.

Way forward

The Centre’s policy on rice exports is unlikely to end with the September 9 decision. Needed are a couple of logical moves to ensure that the original decision works.

The first could be an announcement of a minimum export price to prevent any under-invoicing. The second will likely be regular checks to ensure premium non-Basmati rice that is sold at over $650 a tonne does not get shipped as Basmati rice to escape the 20 per cent tax.

The third will be to ensure that other types of rice are not mixed with Basmati and shipped out to evade the tax. In both these cases, there is a lurking danger of hawala traders operating through this channel.

Over the next few weeks, the government is expected to come up with measures to take care of these concerns. The curbs should also give policymakers time to try and promote Indian rice as a niche product rather than a cheap competitor.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.