Chhattisgarh presents a unique case of the Information and Communications Technologies-enabled Universal Public Distribution System (UPDS) that ensures “food for all” and contributes to the various aspects of food security, such as availability, access, utilisation, stability, and agency. The technological fixes for food security programmes in Chhattisgarh are workable and relevant underlying the political logic of the context.

The co-existence of the National Food Security Act, 2003 (NFSA), and the Chhattisgarh Food Security Act, 2012 has made the coverage of PDS universal in the State. The lessons we draw from the Chhattisgarh’s model of ‘food for all’ would have implications to NFSA evaluation and Integrated Management of PDS.

First, the UPDS has become accessible and portable to the State beneficiaries as it had rolled out the ICTs-driven Centralized Online Real-time Electronic (CORE) PDS in 2011–12. CORE PDS is a predominantly online distribution system but allows limited offline transactions in the case of temporary connection problems at Fair Price Shops or ‘salespersons’ outlet.

Second, beneficiaries in the CORE PDS are allowed to access their ration from any State notified FPS by authenticating themselves through any of the multiple instruments permitted. These include Smart Ration Card issued by the State Food and Civil Supplies Department, Rashtriya Swastha Beema Yojana card issued by the State health department, or a registered mobile number using a one-time password.

Third, the FPS salesperson inserts the smart card in the electronic Point of Sales (ePoS) device that reads the ration card number and sends it to the server through GPRS to obtain the beneficiary entitlement balances.

Fourth, the FPS salesperson enters the quantities issued to the beneficiary and submits the transaction details. The server updates the transaction and generates a success report. A receipt is then printed, and the commodities or foodgrains are issued to the beneficiaries.

Fair Price Shops of CORE PDS

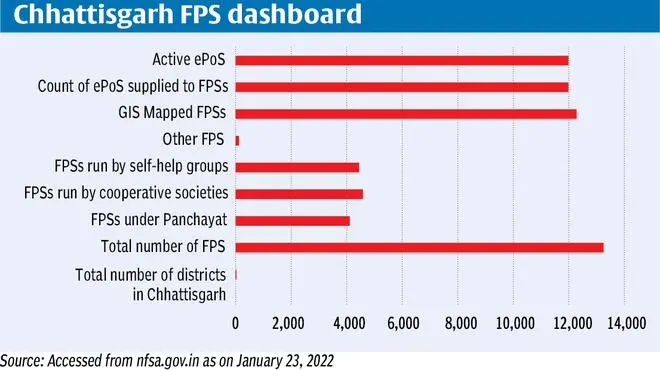

Fair Price Shops play a pivotal role in the technology-enabled food security net. The distribution of FPS as per ownership is presented in Figure 1. Coop societies, Self-help Groups and Panchayats, account for 99 per cent of ownership.

The geo-referenced FPS includes 12,303 which is 93 per cent of the total FPS. 90 per cent of FPS are supplied with the ePoS machine and except for one, all are operational.

According to the Directorate of Food and Civil Supplies, Chhattisgarh, 200 ePoS machines have been installed in urban FPS.

In many places, ePoS was installed and ready for its first-time use. Most FPS in rural regions utilise tablets, and the ration has been distributed via clicking the photograph of beneficiaries.

Such systems can obscure the transparency of UPDS in the State, which flaunts the promises of technology-enabled CORE PDS (Nasscom, 2022).

Chhattisgarh's model of UPDS symbolises "food for all" and is a milestone when it comes to the credibility and portability of the PDS. CORE PDS offers freedom and convenience to beneficiaries in selecting FPS or salespersons. However, this model or system has some shortcomings.

First, the State Food and Civil Supplies Department’s formula to calculate beneficiaries’ entitlement for NFSA or UPDS is complicated. Beneficiaries with 1, 2, or 3 members are not sure whether they are eligible to receive the NFSA or UPDS entitlements. Even the officials of the Food and Civil Supplies Department are not on the same page when asked about it.

A linear or straightforward formula to calculate the allocation per beneficiary would not only ensure equity of distribution. It can also ensure parity among cardholders irrespective of the number of registered members on a particular card.

Second, beneficiaries often receive kerosene, sugar, and salt along with rice. On the downside, many beneficiaries, especially in urban regions, prefer to receive wheat and pulses. This makes sense as rice alone cannot be enough for dietary requirements and provide adequate nutrition to adults and children.

Third, “food for all” is not in sync with a rational approach when the beneficiaries are way above the poverty line entitled to subsidised foodgrains under the State food security act. Instead of the State-adopted UPDS, the NFSA model can rationalise the distribution and reduce the fiscal strain for the State under TPDS.

Fourth, while the CORE PDS mirrors the ONORC portability, an underlying theme of concurrent evaluation of NFSA Phase II (2020-23), beneficiaries under the State food security act (CGFSA) are not found eligible to avail ONORC portability.

To conclude, it is proposed that ePoS and digitisation can address the problem of ghost or bogus cards, and there should be a proper display of Information, Education, and Communication materials at the FPS outlet to discourage overcharging of foodgrains by FPS or salespersons.

Dey is Chairman of CFAM, IIM Lucknow, and Vatsa is pursuing M. Tech at A P J Kalam Technical University, Lucknow. Views are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.