The calendar year 2021 was a landmark in the annals of Indian capital markets. A record 65 entities — corporates, financial institutions, and investment trusts — raised a whopping ₹1,31,417 crore ($17.60 billion) equity through IPOs, which was 75 per cent higher than the previous all-time peak of ₹75,279 crore in 2017.

Investors enthusiastically over-subscribed to 64 of the 65 IPOs, with the lone IPO that garnered just 79 per cent of the targetted issue size surprisingly being the Rakesh Jhunjhunwala-backed Star Health and Allied Insurance. With the government announcing that it is likely to sell up to 5 per cent of its stake in LIC through India’s largest IPO to date and 33 more companies looking to raise ₹60,000 crore filing for SEBI’s approval, 2022 is likely to be another blockbuster year.

While investors flocked to invest in IPOs, one-third of these mostly well-received issues are quoting at less than the issue price as of February 18, 2022. Now is the apt juncture to raise three crucial queries in investor interest. First, how did India Inc. deploy the IPO proceeds. Second, were the valuations ‘fair’? Third, what may be done to enable investors make better-informed decisions? To answer these questions, we analysed the 30 largest IPOs of 2021 that together garnered ₹1,09,905 crore, which accounted for close to 84 per cent of the aggregate IPO proceeds.

Jackpot for pre-IPO investors

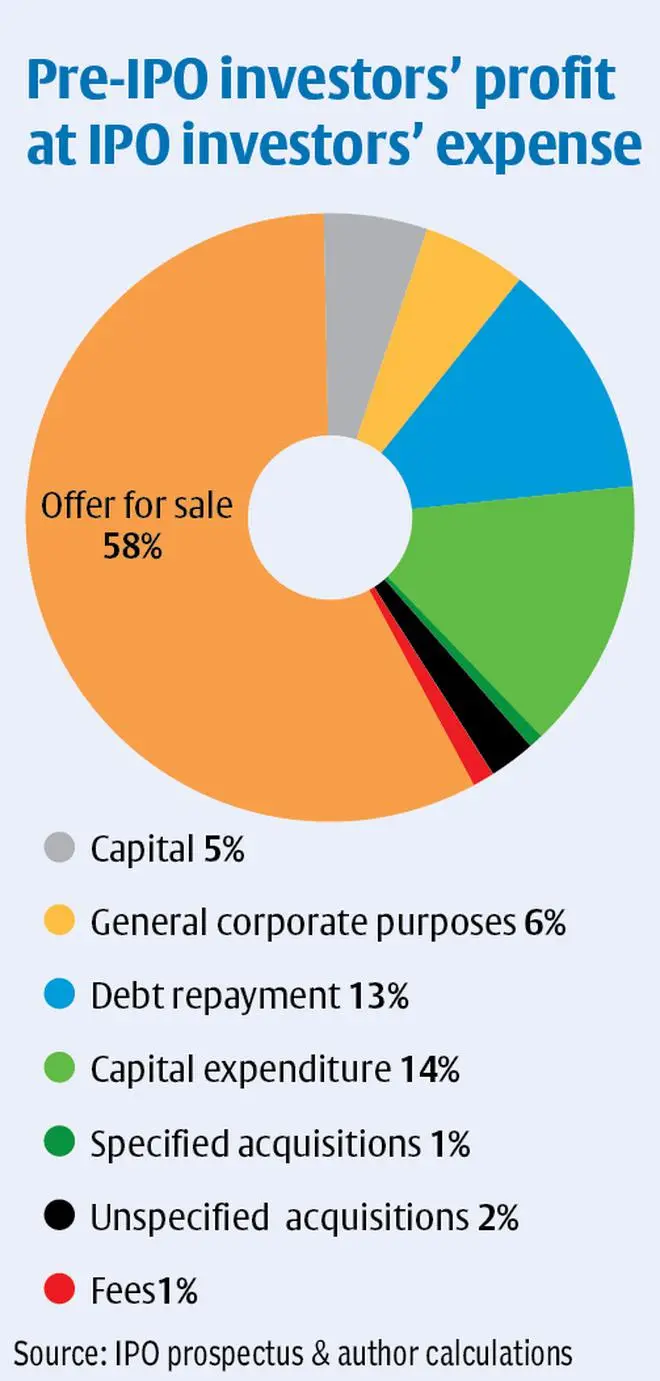

The end-uses of IPO proceeds are a key determinant of future equity returns. Offers for sale (OFS), which is pre-IPO investors selling their stakes during the IPO, accounted for 58 per cent of the 30 largest IPOs. While pre-IPO investors including promoters justifiably sold a part of their stakes at a profit, more than half of the 2021 IPO monies augmented the pre-IPO investors’ personal net worth and was not invested in their companies.

Capital expenditures were a distant second consuming 14 per cent of monies raised followed by debt repayment (13 per cent), general corporate purposes (6 per cent), banks and insurance companies raising capital (5 per cent), and specified and unspecified acquisitions (3 per cent). Fees paid to banks and stock exchanges was an eye-watering ₹1,290 crore or 1 per cent of IPO proceeds.

Performance, peers and valuations

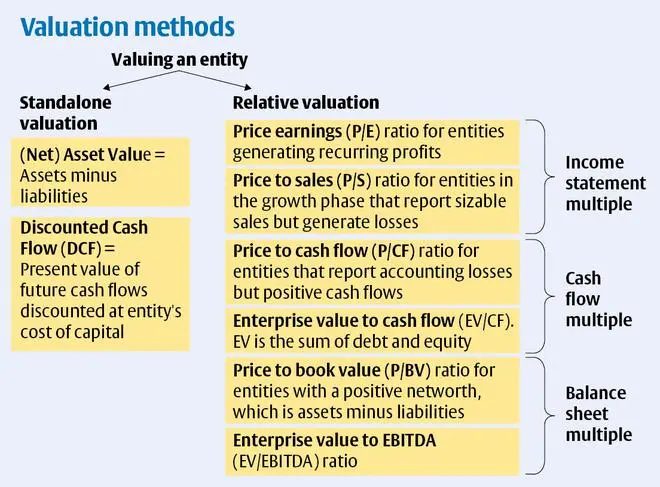

The valuation of an entity or the pricing of its shares during an IPO is a subjective exercise that includes qualitative and quantitative elements. Factors that drive IPO pricing include the macroeconomy, the industry an entity operates in, investor sentiment, operating and financial performance, capital structure, management quality, governance, prospects, and the valuation of its peers. Analysts use stand-alone and relative metrics to estimate an entity’s value.

Notwithstanding the plethora of multiples available to value entities operating in diverse industries and at different points in their life cycles, P/E ratio has been the preferred metric for 29 of the 30largest issuers. This enabled six issuers, who were loss-making, not to provide a quantitative justification for their valuations; a negative P/E ratio is meaningless.

Nine issuers, of whom four are loss-making, claimed that their business models have no peers in India. One issuer stated that “the offer price of ₹76 per equity share was determined by our company in consultation with the selling shareholder and the managers, on the basis of assessment of market demand from investors for equity shares through the book building process, and was justified in view of the above qualitative and quantitative parameters” and three of the four quantitative factors were either ‘NA’ or negative.

Pramad Jandhyala, Co-Founder and Director at LatentView Analytics, whose IPO is India’s most subscribed to (326.49-times) to-date, opines that “Valuation should be reasonable and exciting for IPO investors and the issuer; a win-win for both. Issuers with financial investors looking to exit through the IPO may however have other considerations.”

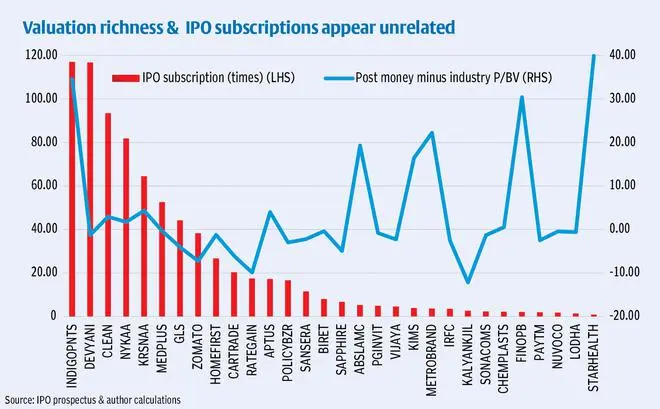

In a nation characterised by low financial literacy, issuers floating gargantuan IPOs without providing adequate justification for valuations did not dampen investor enthusiasm. We mapped the ‘richness’ of valuations and the subscriptions the 30 largest IPOs received. Richness, in this case, is defined as the issuer’s post-money price-to-book value (P/BV) ratio minus the industry average.

The takeaways from this exercise are two-fold. First, correlation between valuation richness and over or under subscription of the 30 largest IPOs was negligible at 0.08. This implies most investors may not have considered valuation richness before making investment decisions. Second, with the exception of Nykaa, the post-money P/BV of internet companies — Paytm, Policy Bazar, Car Trade, Zomato, and Rate Gain — was lower than their respective industry averages.

While Nykaa’s share price is at about 25 per cent over the issue price (the appreciation was 100 per cent on the day of listing), share prices of most internet companies are currently trading below their IPO price. More research is required to refine the valuation methodologies for Indian corporates, especially internet companies, unicorns and, in particular entities that have not provided the path to profitability.

SEBI’s role

SEBI’s preamble states that it has the dual responsibility of protecting investor interests and promoting the development of and regulating the securities market. While it is undesirable and infeasible for SEBI to vet IPO pricing, the regulator must put in place a mechanism to protect investor interests.

First, SEBI must make it mandatory for issuers to provide a quantitative basis for their valuations. Loss-making issuers must report their P/S, P/BV or P/CF multiples in the IPO prospectus. Further, it is desirable for all issuers to report an income statement multiple and either a balance sheet or a cash flow multiple.

Second, SEBI must make it mandatory for issuers who opine they have no peers to benchmark their valuations with a thematic or market capitalisation index or report their stand-alone valuation.

Third, all issuers must be required to include a two-page summary in the IPO prospectus that comprises operating and financial performance track record for at least three years, key risk factors, end use of proceeds, and basis of valuation.

Fourth, all brokerages must provide a two-page independent assessment of the IPO which ought not to be authored by the brokerage or its associates. Further, the report’s author must report the source of compensation — brokerage, issuer, investors, or pro-bono. Investors may place orders for the IPO only after confirming they have read this two-page summary.

IPOs enable investors diversify investments and boost India’s capital formation which has declined from 39.8 per cent of GDP in FY11 to 32.2 per cent in FY20. To sustain investor participation and ensure that their confidence in capital markets is not eroded, issuers must price IPOs fairly and transparently and SEBI must equip investors with the necessary tools to assess risks and potential returns.

Sriram is a Partner at Sammati Consulting and Analytics LLP, and Nandini is the Head of Research at Korea Development Bank. Views are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.