Foreign portfolio investors can make or break the stock market. This is one truth which everyone who tracks Indian markets agrees on. Though the domestic retail and institutional investors can support stocks from caving-in, data show that FPI purchases or sales have a far greater impact on stock price movement.

The reason why Indian stocks are eager to tango with FPIs is because they are largest category of investors after promoters, and hold around 40 per cent of India’s free-float market capital. Though they are not a homogenous bunch and include the staid global banks, pension funds and multi-lateral agencies as well as the more swash-bucking hedge funds, their actions tend to be herd-like.

This is not surprising given that they are influenced by similar factors — global interest rates, global liquidity and relative growth prospects of the economies. Also, since over 50 per cent of the FPIs investing in India originate from the US and another 20-30 per cent from the UK and Europe, the monetary policies and financial conditions in these regions drive the ebb and flow of FPI funds into all markets including India.

With the FPI fraternity returning to Indian shores after a two-year hiatus, stock markets are already in a fuddled state. There are many uncertainties facing India Inc at this juncture and Indian markets are also among the priciest. Additional demand created by FPIs is likely to drive valuations haywire.

Why the sudden spurt?

A look at the net foreign portfolio flows over the years shows that India has received large amount of inflows when the US Federal Reserve, ECB, Bank of England, etc., opened the liquidity spigot, as was witnessed in the period 2009-10 to 2017-18. The post-pandemic stimulus too resulted in an inflow of ₹2,74,032 crore in 2020-21.

India and other emerging markets are once again in a sweet spot now. The Fed and other large central banks are likely to pause the rate hikes and consider reducing rates by the first quarter of 2024. The dollar index has already lost 10 per cent from its peak last October as global funds move away from the haven of US dollar into riskier assets.

FPIs have turned net buyers in Indian equity markets since March this year, purchasing around ₹48,600 crore of stocks since then.

What does this mean?

It may be recalled that Indian markets had been quite resilient in 2022 with the benchmark Nifty 50 managing to hold steady and close on a flat note last year, even as other global markets underwent deep corrections, exceeding 20 per cent in some cases.

Though Nifty 50 declined about 5 per cent since the beginning of 2023, the inflow of FPI funds since the second half of March has lifted stock prices. The Indian bellwether is currently just 2 per cent away from its life-time high recorded in December 2022.

The foreign portfolio flows could be driven by the relatively stronger growth outlook for the Indian economy. The United Nation’s World Economic Situation and Prospects report for mid-year 2023 noted, “India’s economy — the largest in the region — is expected to expand by 5.8 per cent in 2023 and 6.7 per cent in 2024 (calendar year basis), supported by resilient domestic demand.” Other economists have also been projecting a robust growth outlook for India.

But the problem is that corporate earnings are likely to be hit by higher interest rates, slowing demand and weak global markets.

Current stock prices do not reflect the uncertainties and valuations appear pricey. If FPI money creates more demand for Indian stocks, the market will get overvalued.

At long-term average

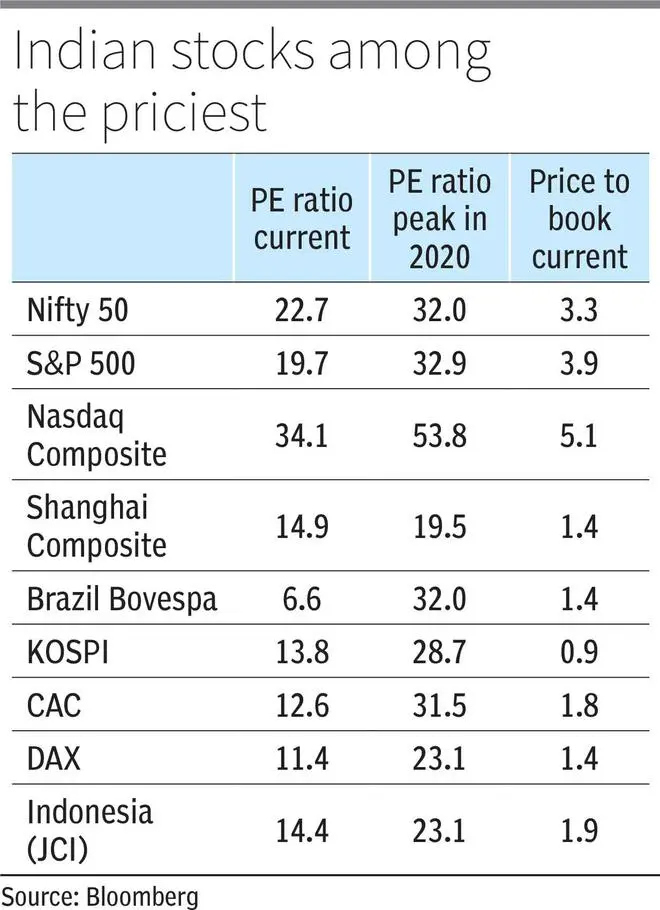

Nifty 50’s trailing 12-month price-earning ratio is currently at 22.7 according to Bloomberg. This is well below the high of 40, hit in February 2021 when the FPI-led rally from the Covid lows had taken prices higher despite deep distress being faced by firms. The Nifty 50 PE is currently close to its 10-year average of 22.57, which makes it rightly valued.

But it needs to be noted that the Indian market is far pricier than all other emerging markets, based on the price-earning ratio. Chinese benchmark, Shanghai Composite trades at 14.9 times while Brazil’s trades at 6.6 times. Only the US’ Nasdaq is pricier than India with a PE ratio of 34.12.

In terms of price to book value too, the Nifty 50 looks more expensive. The P/B ratio of Nifty 50 declined to 2.5 in 2020 and rose to 4.5 by October 2021. But this ratio has not corrected since then, unlike the PE ratio. The price to book ratio of Nifty 50 currently stands at 4.27, only slightly lower than the peak value.

Book value is arrived at by deducting the liabilities and intangible assets from a company’s total assets. Reasons why the price to book value has not moderated is because the debt of India Inc has reduced since the pandemic, while the companies have not added to their assets materially. This has kept the P/B ratio of India among the highest globally.

No way out

As foreign investors look for an economy which is relatively resilient and has a large domestic consumer base, they are landing on India. But with market valuation being fully priced and some consumer-oriented sectors such as FMCG, retail and insurance trading at sky-high valuations, more demand for front-line stocks from FPIs will drive stock prices to the over-valued zone.

Unfortunately, there is little that can be done about this. The country needs this inflow to buttress the capital account and the market is a slave to liquidity. There have been periods when excessive liquidity has driven stock prices higher, even while earnings were slowing. Such a scenario can repeat if the flows continue into India.

With foreign investors restricting themselves to the top 100 stocks, the benchmark indices will remain elevated and trudge higher. The long-term valuation will have to eventually adjust higher if this scenario persists.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.