Agriculture was one of the few sectors that remained resilient in the last two years, even as several sectors globally were ravaged by the Covid-19 pandemic. But now, concerns have emerged, and the near-term outlook seems a little hazy.

Global headwinds

This is because the sustainability of agriculture across the world has come under question now. Global warming and the resultant climate change have led to erratic rainfall. With the abysmally-low rainfall in Europe and China, rivers, which were not only the source of water for agriculture, but were also used for transportation, are on the verge of drying up completely. Sample this: The water levels in Europe’s Rhine river, which is the second largest river and the most travelled waterway used for transportation of a variety of goods from grains, chemicals to coal, has dwindled by more than half. This has resulted in a reduced load of goods being transported through the river, with ships now sailing at 25-35 per cent of their capacity to avoid running aground.

Likewise in China too, the longest heatwave in 60 years has caused several rivers to dry up completely, including several parts of the mighty Yangtze. According to Chinese authorities, the current drought has already impacted 2.2 million hectares of arable land.

What does this mean for the global agri sector?

Should the current drought situation continue, cultivation in China and Europe can be at risk. The world would possibly be staring at a food grain shortage, resulting in a surge in global crop prices – food and commercial. While this may be good for farmers, this will compound the current global economic headwinds, with several economies, including India, already waging a battle with inflation.

India impact

The impact for India on account of the drought in these countries may be mixed. On the positive side, higher crop prices globally can also help higher realisation for farmers here, given that the domestic prices tend to follow the global trend, directionally at least. Exporters of food grains may benefit from higher price realisations. On the flip side, for companies exporting agri inputs – agrochemicals particularly, to these markets, especially Europe, the impact may be pronounced. Besides, supply disruptions in China, caused by power shortages and drought, may hamper agrochemical industry in India given its dependence on China for raw materials.

Fertilisers, which is the other agri-input, will see negligible impact since India is a net importer of fertilisers. Any correction in global fertiliser prices may reduce the government’s import subsidy bill. Global recessionary fears, continuing into the year, can help correction in crude prices. This will be positive for fertiliser and agro chemical players, as the raw material for fertilisers and agrochemicals are crude-based.

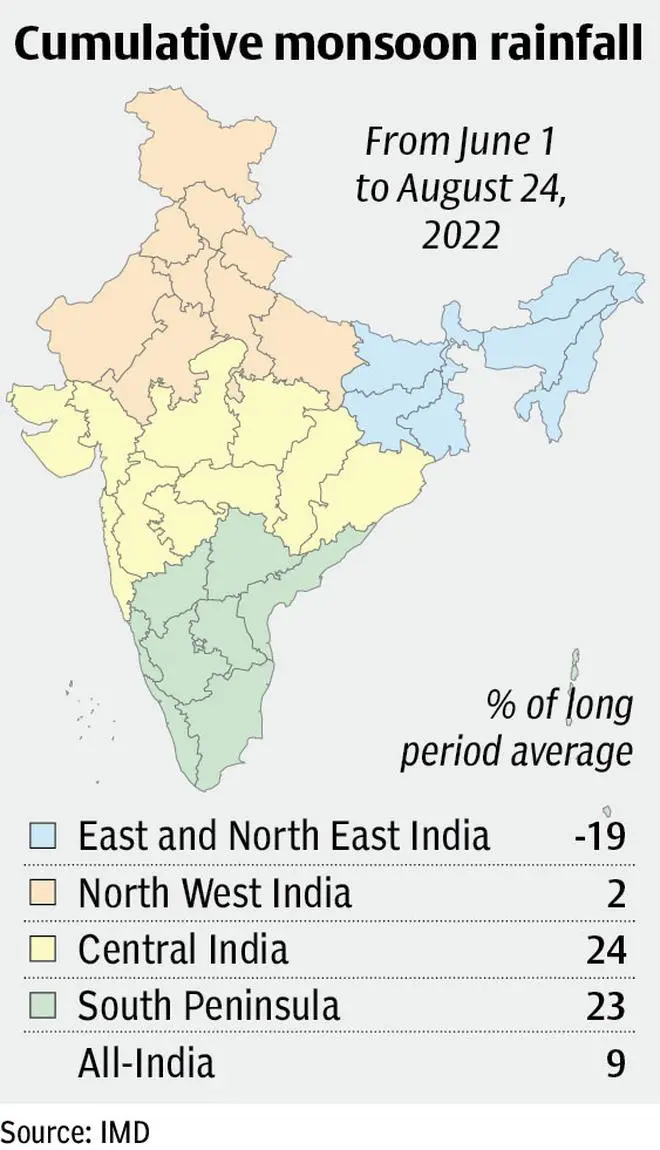

With respect to the domestic landscape, in this year’s southwest monsoon season, while the total rainfall is higher than the long period average (LPA) by 9 per cent, the real issue is with the distribution of rainfall. For instance, East and West Uttar Pradesh, sugarcane belts, received 46 and 41 per cent less rainfall since the start of monsoon till date, compared to the long period average. This can possibly impact sugarcane and sugar production.

Likewise, the rainfall in Jharkhand and Bihar which grow rice and wheat, was lower than the long period average by a whopping 27 per cent and 41 per cent, respectively. In contrast, the southern state of Tamil Nadu received excess unseasonal rainfall, which has damaged several acres of land under rice cultivation. India is possibly bracing for higher food grain costs, given the deficiencies in rainfall distribution. The acreage under cultivation in the current season has been lower by 2.4 per cent on a year-on-year basis, at 101.3 million ha.

In the light of these challenges in the global and Indian agri sector, how should one approach agri-inputs as a space from an investment perspective?

Agrochemicals

Drivers

The growth drivers for the Indian agrochemicals industry over the medium-long term are likely to be four-fold.

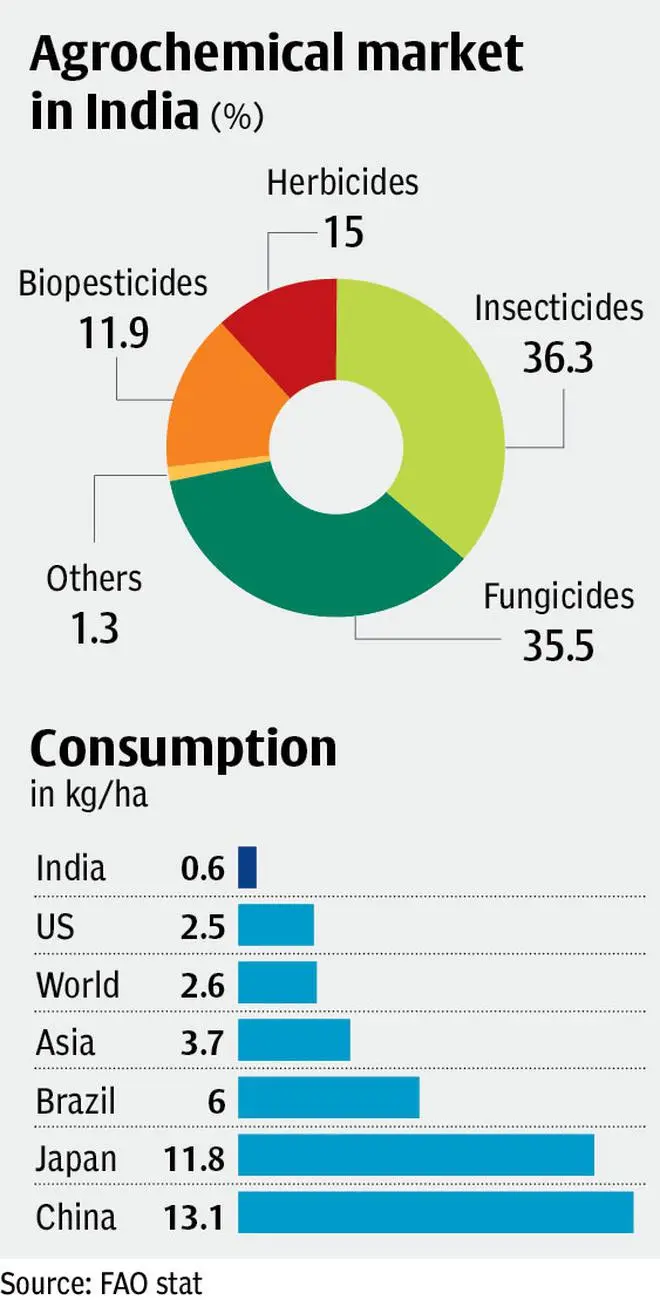

First, currently, the usage of agrochemicals in India is among the lowest in the world. India’s consumption stands at 0.6 kg/ha, and this is just a fraction of that of Brazil, Japan and China, which is at 6 kg/ha, 11.8 kg/ha and 13.1 kg/ha, respectively. Also, currently the crop loss due to pest infestation is quite high at 25-30 per cent and this is on account of lower usage of agrochemicals. Thus, there is immense room for domestic consumption to increase, which should aid growth.

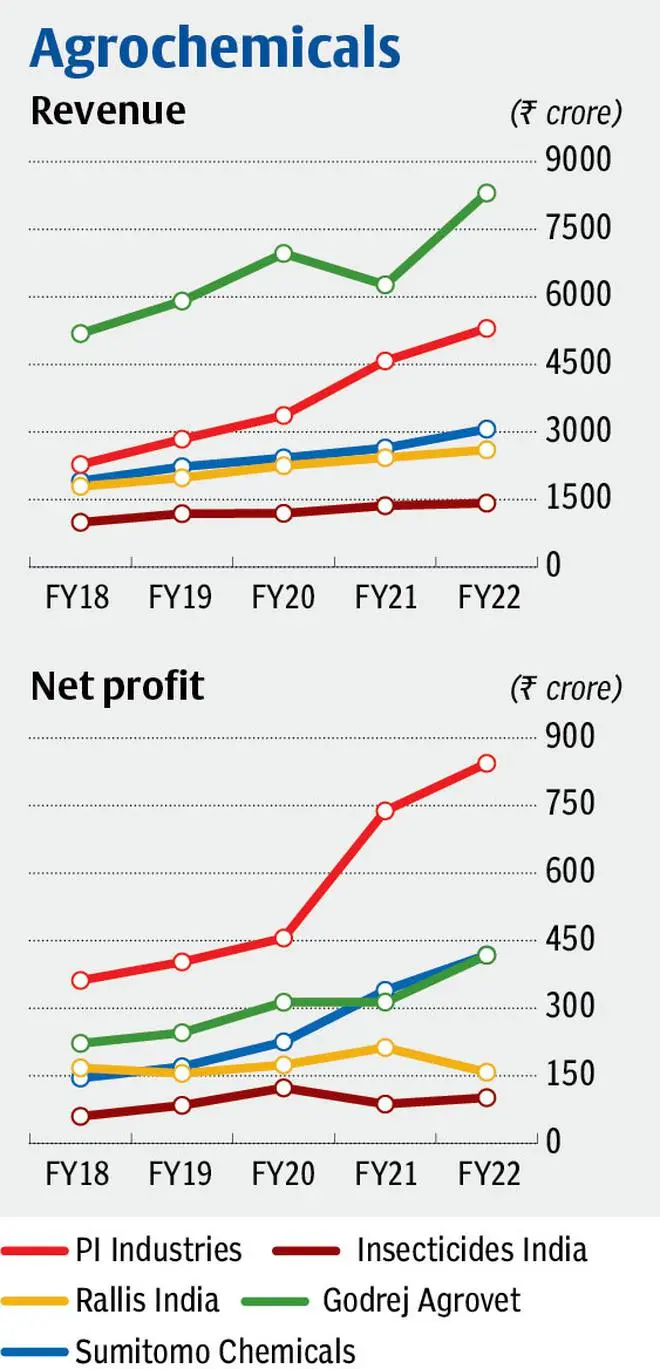

Second, the focus of Indian companies on newer, innovative products and tie-ups with global innovators for research should help them scale their business globally. However, given that innovative product development is time- and cost-intensive, a sound partner with capital and competency is critical for building the novel pipeline. For instance, Delhi-based Insecticides India has collaborated with Japanese OAT Agrio Co through a joint venture entity to set up a research and development unit in Chopanki (Rajasthan) for novel research. The JV has already been granted patents and expects their first novel product to be commercialised by 2025. Such collaborations will help industry scale up their revenue and profit by opening up newer opportunities globally.

Third, new product filing is gaining momentum. For instance, Sumitomo Chemicals, PI Industries and Insecticides India have launched three products each in the June quarter. Rallis and Dhanuka have added two products to their basket, even as Best Agro and Coromandel International topped the list with four launches in the April-June period. Besides generics, companies are also filing for 9 (3) products which are first-in-India launches and will typically enjoy higher margins.

Four, companies globally are adopting ‘China plus’ policy with respect to sourcing technical/key material to reduce dependency on China. This should augur well for India, given its positioning as a low-cost manufacturing destination next to China and its research and development capabilities.

Concerns

Even as opportunities for the industry are looking promising, some concerns remain.

First, there is still a lack of awareness among the farming community regarding new products and growth continues to be driven by older products. For instance, Glyphosate, Monsanto’s innovative herbicide molecule, has been used in India for over four decades and had sales of over ₹1,000 crore last year. This is a fourth of the country’s herbicide market. However, now, agrochemical companies are engaging with farmers and creating awareness to educate and promote newer products. While these initiatives should help increase the volume and value of sales for the industry, it takes a lot of time and effort given that dealers influence the buying decision of farmers in India.

Second, even as companies are investing in novel research, the development cost for novel molecules is high. This adds to the product cost, making it less affordable for the farmers.

Third, the regulation in India needs to be simplified and the registration of products needs to be made easier. India still lags peers when it comes to new registrations. New filings in India are at 273 molecules, vis-à-vis 473 new filings in EU and 527 in Japan.

In the near term though, the volumes in the current season may see some impact due to rainfall distribution – excess rainfall in several States may necessitate re-sowing. However, the industry expects this to average out given the expectation of a better rabi season and higher reservoir storage currently, compared to the previous year.

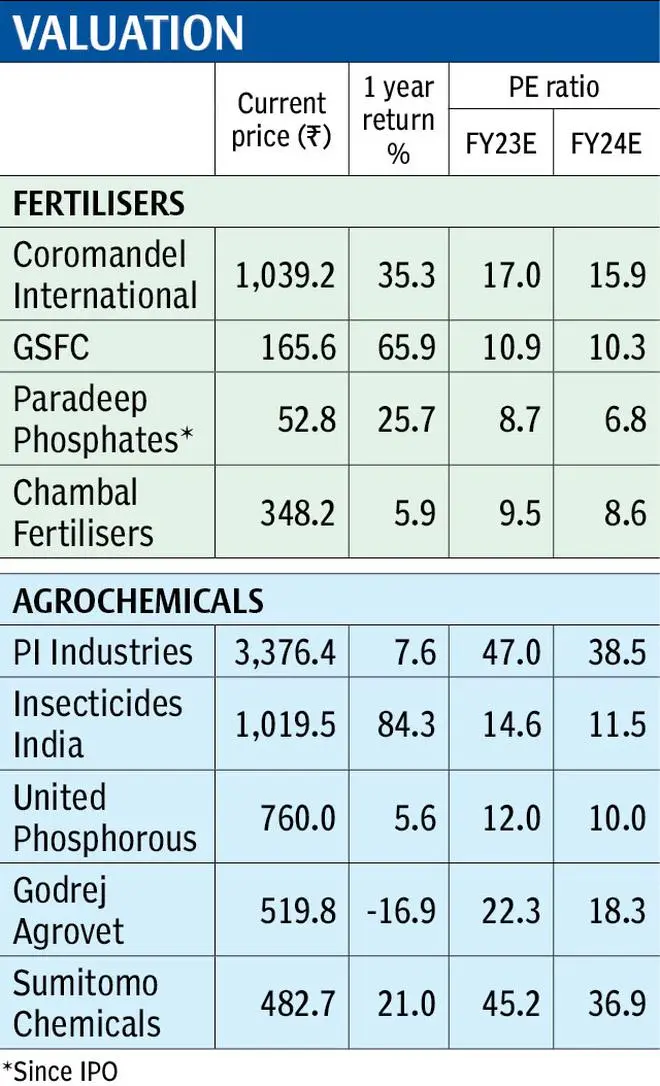

Finally, given that global issues such as climate change and drought may impact export demand, pricing and receivables, domestic-focused players such as Insecticides India (95 per cent from India), Sumitomo Chemicals (80 per cent) may be insulated from global event-driven volatility. Companies that get their lion’s share of revenue from exports include UPL (86 per cent), Sharda Crop Chem (100 per cent), PI Industries (74 per cent), and Meghmani Organics (89 per cent).

Fertilisers

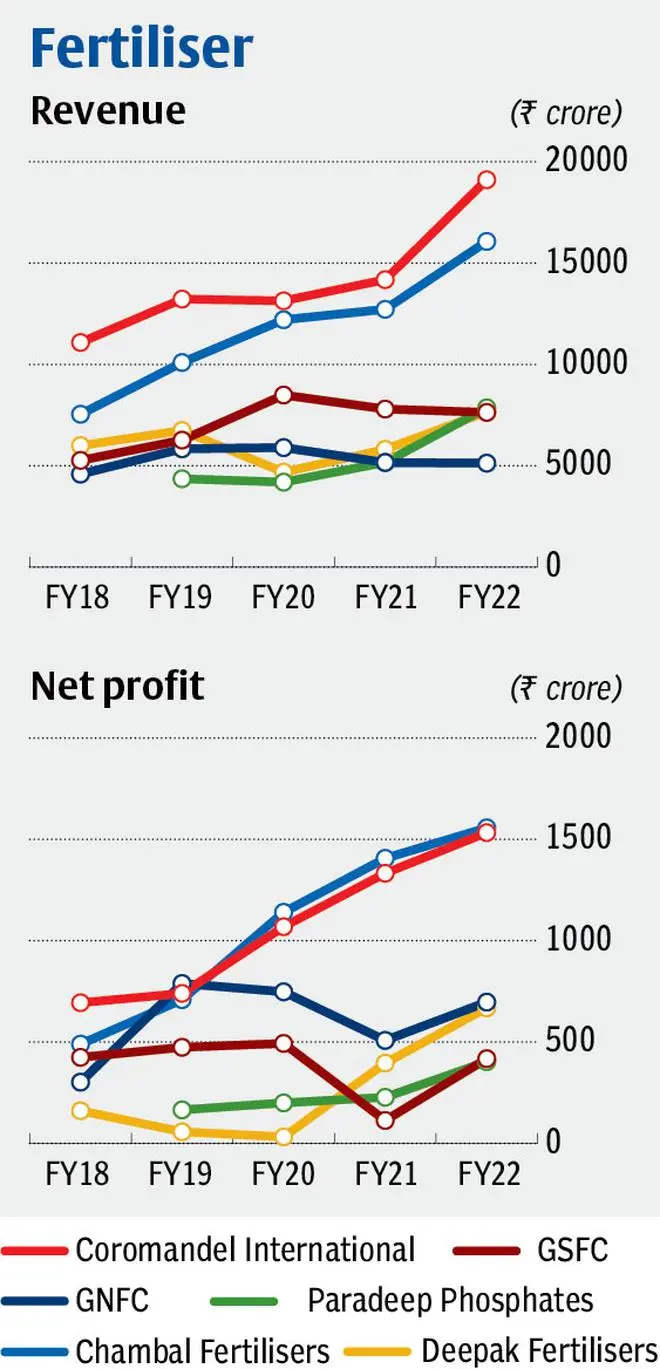

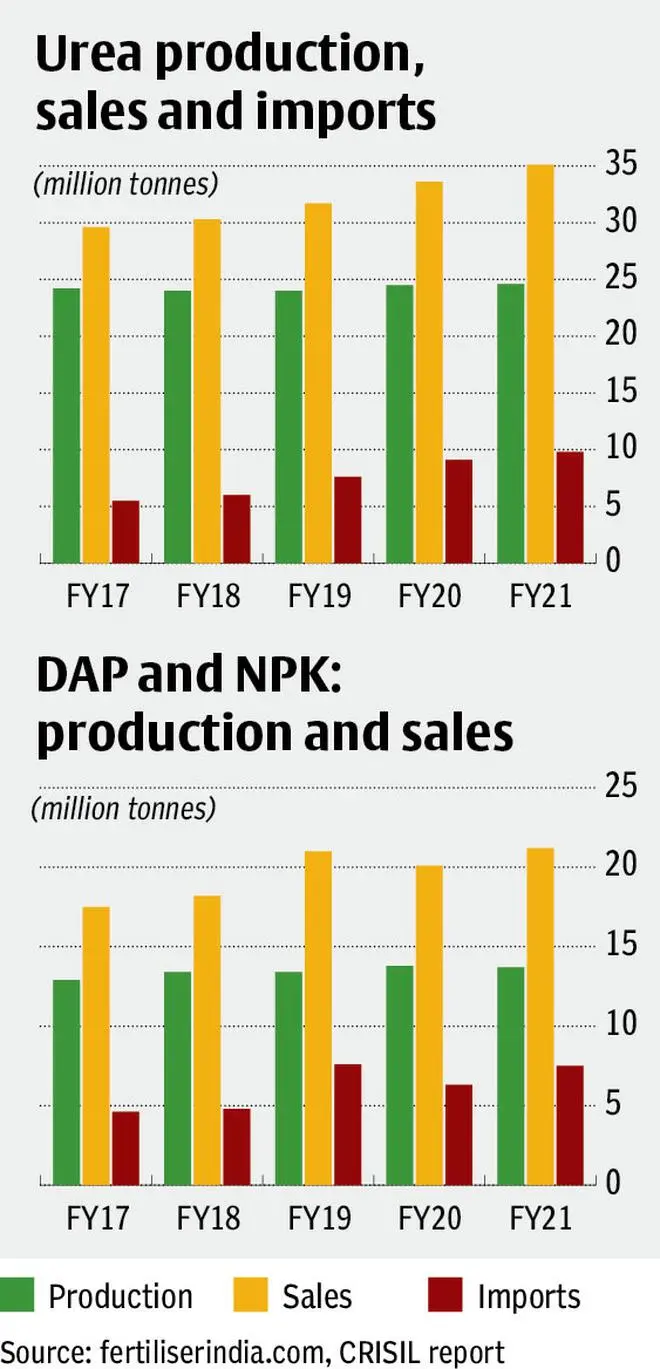

India is among the largest consumers of fertilisers, another key agri input. India meets about one-third of its needs through imports. However, the demand for fertilisers has been resilient given the government’s subsidy support.

In India, the sale price of urea is fixed by the government at ₹5,360 a tonne (before taxes), which is just about one-third of its cost. The balance is paid by the government as subsidy to the manufacturers. This insulates farmers from price fluctuations, resulting in steady demand.

The phosphatic and potassic fertilisers are currently decontrolled. The government fixes a subsidy for every nutrient (say N, P and K) and the balance is recovered from the farmer. Any price increases in the input costs are borne by the government through subsidy and are not passed on to the farmer.

If the drought in China and Europe continues, it can impact the overall global demand for fertilisers. Slack in demand will mean lower prices of fertilisers in the global market.

While the fall in global fertiliser prices will help the Indian government save on its import bill, for urea makers, this may be marginally negative. The reason being that import parity prices are considered while computing the subsidy for urea producers on production over and above their reassessed capacity. That said, any decline in crude and gas prices will be positive for urea manufacturers as well as the government.

India produces two-thirds of the domestic requirement of phosphatic and potassic (complex) fertilisers, while the balance is imported. Hence, the impact of global complex fertiliser price correction will largely benefit the exchequer.

Opportunities

Given this backdrop, the prospects for phosphatic and potassic companies seem more promising. The reason being the policy regime which allows pricing flexibility, increasing demand for decontrolled fertilisers, some of which are differentiated products such as GSFC’s 20:20:0:13, Paradeep Phosphates’ 19:19:19 and 10:26:26, to name a few.

Higher gas prices in the European market, due to non-availability of gas from Russia, has made domestic ammonia production unviable in Europe and this opens up export opportunity for Indian ammonia producers such as GNFC and GSFC.

Concerns

The recent move by the government to sell all fertiliser products as one brand “Bharat” is a concern that has risen now. But it may not have any material impact on fertiliser producers, given that India is a suppliers’ market with demand outstripping supply, hence the production will get absorbed locally. Fertilisers, particularly urea, is a commodity, and offers no differentiation and hence branding does not impact sales materially.

Hence, we do not see any near-term concern on account of the government’s proposal to brand all fertilisers uniformly.

Branding will be critical only when the country’s production outstrips demand, and companies will have to compete hard to sell their product. This, we believe, may be several years away, given that the fertiliser industry has not seen any meaningful investments in the last decade. Also, any new investment in this industry will require a favourable policy environment for companies to commit large long-term capital, given the capital-intensive nature of the business.

Thus, overall, for the agri inputs space, prospects in the medium term are intact, the only wild card being changing monsoon pattern.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.