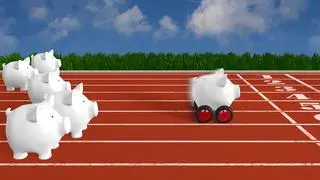

One of the arguments commonly forwarded for justifying the higher premium enjoyed by Indian equities is the country’s relatively stronger growth and other macro parameters compared to the rest of the emerging market economies. “Foreign funds have no other option but to come to India,” has been a common refrain.

But 2016 has weakened this assumption considerably. This shift in preference is captured by foreign portfolio inflows into equity markets in 2016. While Indian equity markets received $4 billion up to December 16 this year, other emerging markets such as South Korea ($9.9 billion) and Taiwan ($11.6 billion) received far higher inflows.

Revival in commodity prices that brought commodity-centric emerging markets back in the reckoning, growing uncertainties for advanced economies and the setback to the Indian economy due to the ongoing demonetisation are some reasons why India appears to have lost its place as the numero uno destination for foreign investors.

Let’s look at the key trends that shaped the global economy in 2016.

Revival in commodity pricesThe global economy has been decelerating since mid-June 2014, led by meltdown in commodity prices. World output growth, according to the IMF, declined from 3.4 per cent in 2014 to 3.2 per cent in 2015.

Emerging economies largely dependent on commodities were the most hurt in this phase. Growth in emerging markets and developing economies fell from 4.6 per cent in 2014 to 4 per cent in 2015.

But there was respite for these countries from February 2016 onwards. The Thompson Reuters CRB spot commodity index revived from 374 towards the beginning of the year to 426; an increase of 31 per cent. Crude oil prices have surged to $52.29; up almost 80 per cent from the February low.

Crude oil prices recovered on expectation of cut in output by oil producers; that finally happened in November. Other commodities also recovered as fears of a hard-landing in the Chinese economy receded; China’s growth stabilised at 6.7 per cent in the first three quarters of 2016 on policy support from the government.

However, the consensus opinion is that a runaway appreciation in commodities is not expected in 2017. Crude could largely be range-bound between $45 and $65 and commodity prices could also peak soon, as slowing demand from advanced economies can be a limiting factor.

Emerging economies rev upThe outlook for emerging markets in general has improved in 2016, thanks to the stability in China and revival in commodity prices. The IMF has projected growth in emerging markets and developing economies to improve to 4.2 per cent in 2016 and 4.6 per cent in 2017. Latin American and Caribbean nations that are projected to grow -0.6 per cent in 2016 are expected to improve to 1.6 per cent growth in 2017. Sub-Saharan Africa is also expected improve its growth rate from 1.4 per cent in 2016 to 2.9 per cent in 2017.

The impact of higher commodity prices has been to improve the value of trade in 2016. According to the IMF, growth in trade volume of goods and services in emerging market and developing economies, which had shrunk to -0.6 per cent in 2015, revived to 2.3 per cent in 2016.

The growth is expected to accelerate further in 2017 to 4.1 per cent, which translates into higher growth for commodity-centric economies. The export growth of emerging markets and developing economies is also expected to improve from 1.3 per cent in 2015 to 2.9 per cent this calendar and further to 3.6 per cent in 2017.

Advanced economies lose steamEven as emerging and developing economies revived, developed economies struggled.

The US economy has decelerated in 2016, with growth in the first three quarters of 2016 ranging between 1.3 and 1.6 per cent. This is much lower than the 3.3 per cent growth in the March quarter of 2015. While consumption in the US continued to be strong, reduction in capital expenditure, especially in the energy sector, impacted manufacturing. A strong dollar was another drag on the US economy. Growth in the Euro Zone is also expected to be slightly lower at 1.7 per cent in 2016, down from 2 per cent in 2015, according to the IMF.

The New Year holds out tremendous uncertainty for both the US as well as the Euro Zone due to two epochal events of 2016 – Brexit and the election of Donald Trump as the next President of the US. Growth for the Euro Zone has been revised lower due to the impact of the UK exiting from the region. The impact of Trump’s election is hard to pencil in just yet and the IMF has projected the US economy to grow 2.2 per cent in 2017. There are expectations that he will unleash massive infrastructure spends and slash taxes, boosting both manufacturing and consumption. But how all this plays out is yet to be seen.

Analysts and economists are also downplaying the possibility of negative impact on global trade and emerging market economies, if Trump pushes through protectionist policies. These will be key areas of interest in the New Year.

Uptick in manufacturingDeceleration in industrial production appears to have bottomed in 2016 and nascent signs of pick-up were observed in the later part of the year.

Manufacturing PMI in China, which was below 50 upto June 2016 (value of less than 50 indicates contraction and above 50 denotes expansion) rose to 50.9 by November.

Manufacturing activity accelerated in the US with the manufacturing PMI rising from 51.2 last December to 54.2 now. The current reading in the Euro Zone is also strong.

This trend is also captured by the world industrial production numbers put out by the IMF. Growth in industrial production, which was a healthy 10 per cent in 2010, dropped to zero towards the end of 2015. There is a mild revival to about 2 per cent growth till August 2016.

Services sector growth, on the other hand, has been quite robust in the US and the Euro Zone in 2016. The outlook in 2017 for services could, however, be a little tepid as banking and financial services companies get hurt by Brexit. If Trump stays true to his promises, manufacturing could do better in 2017 compared to the services segment.

Accommodative monetary policyTowards the beginning of 2016, the most feared event was the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes. The upheaval in the first two months of the year and the vote favouring Brexit in July made the Fed postpone the hike till December, when the Fed funds rate was increased 25 basis points.

While a few more hikes by the Fed are expected in 2017, the central bank is likely to move cautiously, taking the trend in economic data into account. There is also no talk of re-sale of the over $3 trillion of bonds purchased by the Fed during the quantitative easing programs, yet. So there is no threat to global liquidity as of now.

The European Central Bank has promised to continue monetary easing until the end of 2017. It expects interest rates to remain at current or lower levels for ‘an extended period of time’. The Bank of Japan too retained the annual increase in Japanese Government Bonds to 80 trillion yen.

Implications for IndiaBased on the trends discussed above, here are the implications for India under three heads, currency, equity and debt.

Currency: Since India is a net commodity importer, higher commodity prices are seen as a negative for the currency. It may be observed that the rupee was much stronger than other emerging market currencies in 2015 since weaker commodity prices were seen as conducive to India’s external account balance.

It is mainly for this reason that the rupee depreciated 2.3 per cent against the dollar in 2016 even as other EM currencies such as the Russian rouble (18 per cent), Brazilian real (17 per cent) and South African rand (10 per cent) recorded sharp appreciation against the greenback.

The Indian currency is expected to remain under pressure in 2017 too as commodity prices stay firm. That, coupled with a stronger dollar due to the Fed’s impending rate hikes, makes a visit of 70 level against the dollar a possibility. While declining gold imports are a positive, fall in services exports due to the impact of Brexit and the muted near-term prospects for our technology companies can have a negative impact on the currency too.

Debt: Yields of India’s 10-year government securities have recorded a sharp decrease in 2016, among the highest globally. From 7.7 per cent towards the turn of 2016, they are now down to 6.5 per cent, down 125 basis points. The RBI’s move towards neutral liquidity, coupled with the recent demonetisation, has been the key contributor. The falling yields have made Indian 10-year bond less attractive when compared to some of the other emerging economies such as Indonesia (7.8 per cent yield), Russia (10.6 per cent), Brazil (13.6 per cent) and South Africa (7.3 per cent). Lower yields, alongside weaker currency, have made Indian debt far less attractive, resulting in FPIs pulling close to $6.6 billion out of Indian debt this calendar.

Rates can harden if the FPIs continue pulling money out of Indian debt due to US government bond yields rising further. But domestic monetary policy is likely to cap this hardening.

Equity: Outlook for Indian equity weakens against the backdrop of recovery in other emerging markets in 2016.

While the going was smooth for Indian equity up to November, the Centre’s move to ban ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes in November has thrown a spanner in the works. Consumption has been hit and the informal sector is struggling too, with repercussions on the GDP growth likely in the December and March quarter. Services PMI for November plunged to 46.7 in November from 54.5 in October, sending ominous signals.

It is hard to say if this pain will prolong to dent company earnings. Market returns have been hurt by this event. The Sensex’ performance this year has been flat compared to a stronger show by other emerging market peers such as Brazil’s Bovespa (34 per cent up), Indonesia (13 per cent) or Thailand (18 per cent).

With the Fed’s future rate hikes, Trump’s protectionist policies, negative impact of rising commodity prices and the ongoing demonetisation, 2017 could be rocky for Indian equity.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.