When it comes to drafting policy, there is always a risk of missing the woods for the trees. In pharmaceuticals, this risk can amplify the outcome.

The recently released Draft Pharmaceutical Policy reflects sound objectives. For instance, setting the World Health Organisation’s Good Manufacturing Practices and Good Laboratory Practices as the minimum standards; making bio-availability and bioequivalence mandatory for all generic drugs approvals in a phased manner; making the Uniform Code of Pharmaceutical Marketing Practices mandatory; encouraging e-pharmacies and shortening timelines for the drug approval process to three months.

But this farsightedness needs to extend to other areas too. For instance, raising Customs duty on imported APIs (active pharmaceutical ingredients) to the peak rate, while promoting indigenous API manufacturing capability with some concessions, seems to be a knee-jerk reaction. The Draft Policy points to ‘drug security’ as the rationale for such action on APIs. Healthcare security can be achieved only by making the best quality medicines available for patients. Increasing cost on API imports will not only increase the cost of drugs domestically, but also impact India’s cost advantage for exports.

The Draft Policy talks of strengthening innovative research and development, but fails to qualify steps to protect the Intellectual Property of the outcome of such investment. Innovative medicines offer hope to patients, but for the innovator, it is one expensive, long and complex process. IP protection is imperative.

What then becomes a prescription for an ideal policy?

Public health expenditure must be increased from the current 1.1 per cent of GDP to 2.5 per cent of GDP in a time-bound manner, as proposed by the National Health Policy.

Second, there is a need to augment the regulatory framework and strengthen the overall healthcare infrastructure. Third, medicines sold here should be of the ‘best quality standards’.

Last, the promised Universal Health Coverage must take concrete shape. India accounts for the highest private financing of insurance, at 69 per cent as compared to China at 44 per cent. In April 2016, the National Sample Survey found that nearly 86 per cent of the rural and 82 per cent of the urban population had no health coverage. Further, only 13 per cent of the rural population (and 12 per cent in urban India) had government-funded health insurance.

An enabling ecosystem needs to prevail. Persistent and recurrent price control measures are counterproductive to the well-being of the industry. The Draft Policy views price control as a measure to increase access to medicines. Though price control has existed in India since the 1960s, access to medicines continues to be our biggest hurdle. That can be addressed only with a collaborative approach among stakeholders, rather than the myopic price control-centric one.

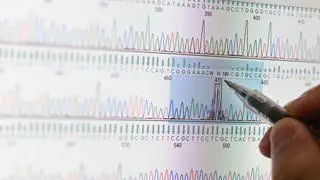

Quality of drugs continues to be a challenge, and Government and manufacturers have a shared responsibility here. Bioavailability and bioequivalence studies play a crucial role in determining drug efficacy, and mandating them will ensure that quality checks are not compromised.

Loan License and Contract Manufacturing bring geographical and cost advantages to manufacturers, and the industry stands to gain from the expertise on improvements in processes and regulatory standards. This aligns with ‘Make in India’ and provides an impetus to economic growth. The current disposition of the Draft Policy that recommends phasing out these business models seems to be a deviation from the otherwise positive directions of the government.

The Draft Policy seems to have the real challenges in healthcare infrastructure largely under-addressed. So, while it may bring in long-term stability, it needs to address key challenges now. Else it could become a policy pill that is more than the industry can chew.

(The writer is Director General, Organisation of Pharmaceutical Producers of India. Views expressed are personal.)

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.