solar panels and windmill power plant istock photo for BL | Photo Credit: loveguli

The NDA’s achievement in clean energy is a story of missed targets. If you look at just the numbers without context, they may appear to be respectable, but against the backdrop of either the government’s own targets or what could have been achieved, they present a rather glum picture.

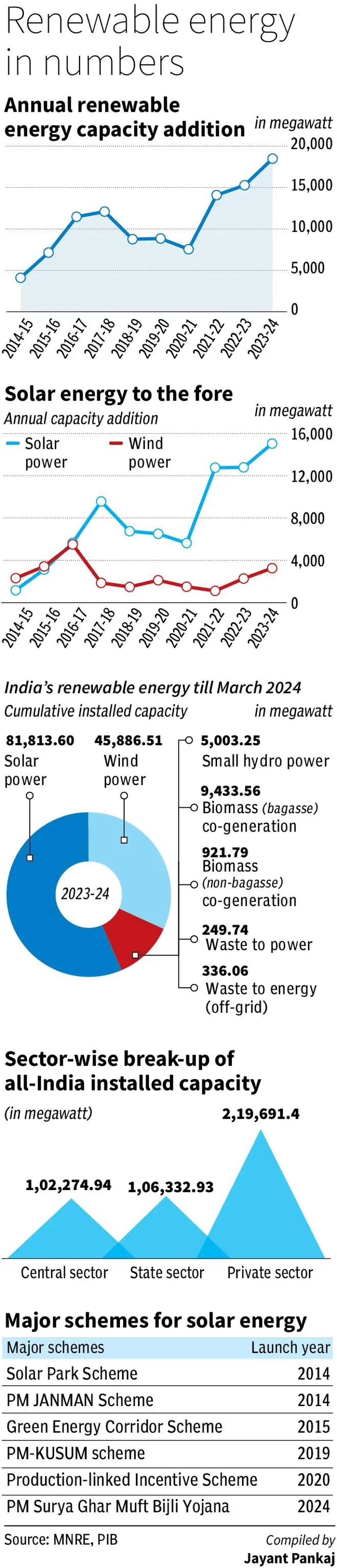

At the end of March 2014 (just two months before NDA assumed office) India’s cumulative renewable energy capacity stood at 35,849 MW. Wind dominated the scene, with 21,042 MW, followed by biomass —mainly, co-generation plants of sugar mills — at 7,419 MW. Solar was just beginning to happen (2,822 MW).

A decade later, the total capacity number stands at around 1,43,644 MW — with wind at 45,886 MW and solar, 81,813 MW. So, in the last 10 years, India has added 11 GW of capacity annually, on an average.

One might indeed argue that these are respectable numbers — particularly because alongside capacity addition, the tariffs of both wind and solar have come down drastically. Wind tariffs used to be fixed by the respective State electricity regulatory commissions and the lowest wind tariff used to be ₹4.16 a kWhr in Tamil Nadu. In 2017, the government changed the method of paying wind energy companies, from fixed feed-in tariff (FiT) to auction-based tariff discovery, because of which the tariffs slid to a historic low of ₹2.44 a kWhr, before rising to around ₹3 now. As for solar, where the method of tariff discovery was always through competitive bidding, the story is fascinating. From a high of around ₹18 a kWhr around 2014, tariffs slid to ₹2.43 (₹1.99 in one case) and are now ruling around ₹3. In the case of solar, only a small part of the credit should go to the government, because tariff decline happened essentially due to the fall in the prices of modules, driven by overcapacities in China —from around $1 per Watt-peak around 2011-12, to as low as 14 cents today.

All these numbers may appear to arm the government with a right to claim success, but there is flipside to the story.

As soon as the NDA government assumed office in May 2014, it upscaled the targets for renewable energy capacity to be achieved by 2022 to 175 GW (100 GW of solar, 60 GW of wind and the rest small hydro and biomass). Previously, the UPA government’s target was 20 GW for 2022. Even two years after that year, the achievement is nowhere near the target.

When it became clear that the 2022 targets would be missed by a wide margin, the government quietly changed the goalpost, fixing fresh target of 500 GW for 2030. (This is for any ‘non fossil fuel’ based energy, but since large hydro and nuclear are very difficult to build within the time-frame, the target essentially means wind and solar.)

To understand why the targets were missed, it is necessary to analyse wind and solar separately.

The wind sector, which held a lot of promise, has been crushed by the government’s desire to pin down tariffs. In 2017, the government (overruling the industry’s protests) brought in tariff-based competitive bidding, where the company that offers to sell electricity at the lowest prices would get to sign a long-term power purchase agreement with the government company, SECI. It appeared to be a good idea to leave prices to the market. But soon it became evident that it was not working because bidders bid too low, on the edge of viability, to win projects but later gave them up even if that meant losing the earnest money deposit. It was clear that the ‘reverse auction’ method (under which bids and counter bids continued even after the initial bids were opened) was just not working. Tenders started getting tepid responses. For example, in February 2023, SECI floated a tender for wind power (SECI XIV) — it was for 1,200 MW but attracted bids only for 690 MW. Yet, the government refused to change tack fearing a rise in tariffs. Finally, in 2023-24, the government tweaked auction method to ‘closed auction’.

The numbers illustrate the story. The year 2016-17, when companies rushed to put up capacities before some incentives expired, the capacity addition was 5,502 MW — an all-time high. Then began the fall. If only the government had ensured that the energy companies got a reasonable tariff, India’s wind capacity would have met the target.

As for solar, the issue was with the ‘rooftop’ segment. The 100 GW target for solar had been split as 60 GW for utility scale (large) projects and 40 GW for rooftop plants. Businesses and individuals putting up rooftop solar plants met with stiff resistance from the State utilities. As a result, the rooftop solar segment has been a laggard. At the end of December 2023, India had rooftop solar installation of 10.5 GW — way below the target.

Furthermore, there has been a huge delay in India’s foray into offshore wind. After much dithering, the first tender for offshore wind, for 4 GW, was issued in February. It is on ‘you put up, you sell’ basis, with no financial support from the government. Also, the government has shown little vision in exploring other promising sectors like ocean energy.

Published on April 30, 2024

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.