The environment cess collected must be used for what it was intended -- to reduce emissions and coal use | Photo Credit: DEEPAK KR

The government has made climate pledges under the Paris Agreement that includes reducing emissions to GDP ratio (emissions intensity) by 45 per cent by 2030 compared to 2005 levels.

The Clean Environment Cess (CEC) was a tax introduced in 2010 as a fiscal tool to reduce the use of coal and associated carbon emissions, and whose revenues were earmarked for financing and promoting clean environment initiatives. It was levied on the total sales of all types of coal in India.

To manage the funds accrued under the CEC, the National Clean Energy & Environment Fund (NCEEF) was created in 2010, and the funds were hypothecated for environmental goals such as rejuvenation of rivers, afforestation, and promotion of renewable energy generation through research and development.

Despite these intentions of levying the cess, its design and implementation have been inadequate. Our recent study at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP) analyses the issues associated with the implementation of the CEC and its usefulness in combating the increasing pollution levels in India.

The findings of this study show that, first, the design of the CEC, which levies the cess in proportion to only the quantum of coal (at ₹400/tonne), without differentiating by its grade, does not give an incentive to switch to higher quality coal with lower levels of pollution.

Second, this cess was subsumed into the Goods and Services Tax (GST) compensation cess in 2017, and the revenues, which were originally earmarked for environmental conservation, was instead used for compensating States for their loss of revenues.

Instead of having designated funds for clean energy and environment initiatives, it is now at the discretion of the States to determine where their revenues from the GST compensation cess are being spent. This calls for an immediate review and also highlights the inefficiencies of the government’s fiscal operations and the reduced attention given to promoting clean environment schemes.

Third, the data on revenue utilisation from this cess indicate that only 18 per cent of the aggregated revenue collected between 2010-11 and 2017-18 was used for its intended purpose. This again points out the inefficiency of the government in using the revenue of a cess for its earmarked purposes.

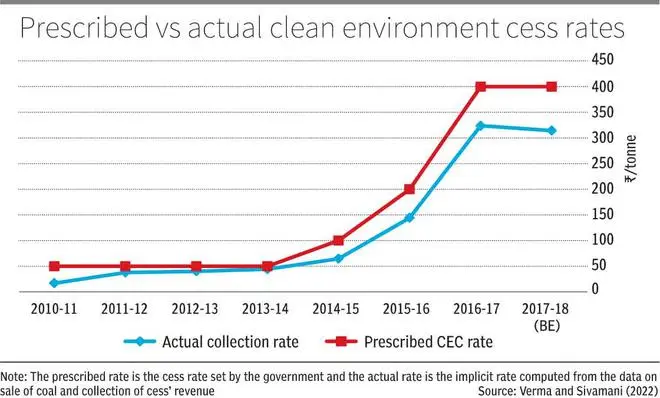

Fourth, and significantly, the study finds that there is an inadequacy by the government in collecting the revenues owed from this cess. The difference between the prescribed rate and the actual rate of collection has widened since 2013-14 (see graph). While the rate of this cess was ₹200/tonne and ₹400/tonne in 2015-16 and 2016-17, the actual collection rate per tonne of coal was only ₹144 and ₹324, correspondingly.

The gap of ₹56 and ₹76 per tonne of coal sold in India led to an estimated revenue loss of around ₹4,900 crore and ₹6,700 crore, respectively.

Finally, despite the doubling of the rate of CEC from ₹200 to ₹400/tonne in 2016-17, the modelling experiment showed that the effect on the emissions reduction was meagre. The emissions from the burning of the coal and petroleum products in various industries decreased by only 0.90 per cent in total.

Additionally, the doubling of the cess had a marginal impact on the GDP, with a reduction of 0.09 per cent. The emissions intensity of the economy thus reduced by just 0.81 per cent, compared to the effective 20 per cent tax imposed on the price of coal. This shows that the cess was not very useful in reducing the emissions intensity in India vis-à-vis its high tax rate.

The government cannot rely on a fiscal tool such as the poorly-designed CEC. The government must introduce a graded form of an ecological tax that is levied on the value of outputs of sectors such as coal, electricity, fertilisers, iron and steel, non-ferrous basic metals, paper products, and textile industries. This would be in contrast to the CEC, which was levied on the sale of coal, and coal is not as polluting as these sectors.

Further, this will help broaden the tax base. Various studies indicate that these industries are the most polluting, which not only release air pollution, but also have adverse impacts of water pollution and land degradation. Thus, a tax on their outputs, and not necessarily on their emissions (as these taxes are more difficult to monitor, compute, and collect), may help India provide industries a proper incentive to move away from polluting forms of production to cleaner mechanisms.

Most importantly, the proceeds from such taxes must be used in an ecological sensitive manner by sticking to the desired objectives of promoting clean environment projects and meeting the country’s climate change mitigation targets.

Verma is Associate Fellow; and Sivamani is Research Associate, Centre for Social and Economic Progress

Published on November 3, 2022

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.