The note ban did not transform India into a cashless economy | Photo Credit: PERIASAMY M

In a fateful speech on November 8, 2016, Prime Minister Modi announced that the two largest denomination currency notes — ₹500 and ₹1,000 — would cease to be legal tender overnight. Citizens were given 50 days’ time to deposit their old notes with banks. The promise was that the short-term pain inflicted on citizens would be made up by cracking down on black money, terror financing and counterfeit currency.

Eight years on, it is clear that demonetisation didn’t really deliver on its original objectives of throwing the black economy into disarray. It did, however, result in unexpected wins on digital adoption and tax compliance.

Some likened demonetisation to shooting at the tyres of a speeding car. That was an apt description because when the announcement came, India’s real GDP growth was racing along at 8-9 per cent. Cancelling 86 per cent of the currency in circulation in one fell swoop was unprecedented, especially with no gameplan in place for quick remonetisation.

Immediately after the note ban, transactions in farm produce, MSMEs, retail and real estate where cash was in vogue, all but froze up. Informal entities bore the brunt of the cash shortage, while formal ones that accepted cards or bank transfers gained.

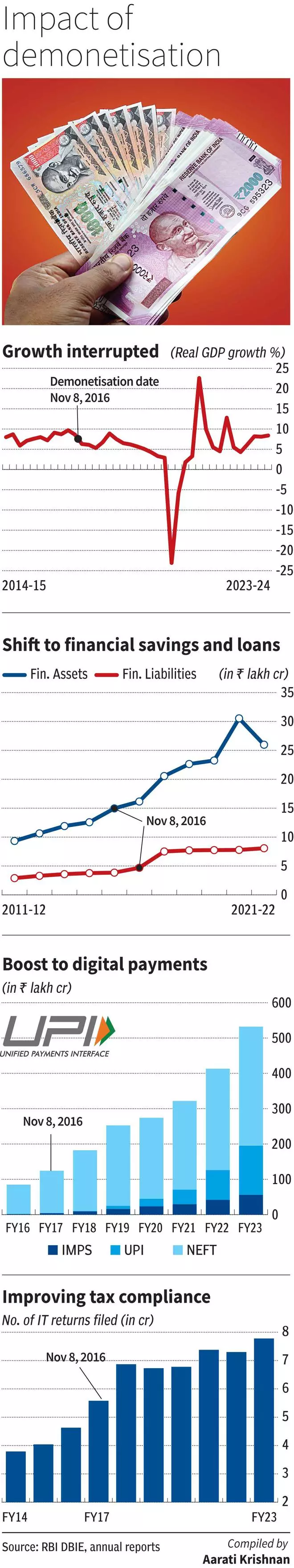

Official GDP data today, after revisions, show that India’s real GDP growth which ranged 8.6-9.7 per cent between Q4 FY16 and Q3FY17, skidded to 6.3 per cent in Q4 FY17. Growth stayed sub-par for three more quarters before normalising. Both the consumption and investment legs of the economy took a knock. GST implementation which followed close on the heels of demonetisation in July 2017, proved disruptive too. This ensured that Indian consumers and businesses were back to even keel only by Q4 FY18.

That demonetisation did not leave a lasting mark on consumer confidence or faith in paper currency, is testimony to the stoicism of the aam aadmi in India who is willing to quickly move on from adversity — a quality that was evident after Covid too.

The note ban did not transform India into a cashless economy though. A recent RBI paper noted that, despite the big take-off in digital payments since FY18, currency in circulation has expanded from 8.7 per cent of GDP in FY17 to 12.7 per cent by FY23.

It was expected that demonetisation would force those engaged in illicit activities to destroy their old notes. But this was underestimating the Jugaad capabilities of the black economy. By June 30 2017, of the ₹15.45 lakh crore worth of notes that were demonetised, ₹15.28 lakh crore or 99 per cent, had returned to banks.

News reports spotlighted many methods which hoarders of black money used to recycle their notes. Some fabricated back-dated receipts, others used newly opened Jan Dhan accounts as mules. Bags of notes were smuggled via banks’ back doors to be laundered, with the help of friendly staff.

In 2017, the Finance Ministry said that 18 lakh bank accounts had come under tax scrutiny due to mismatches between reported incomes and deposits.

But it is doubtful if this exercise netted big fish. The rising number of Enforcement Directorate and income tax raids in recent years that have unearthed roomfuls of cash, show that the black economy continues to thrive.

On counterfeiting, RBI annual reports show that the number of counterfeit notes detected have fallen from 7.62 lakh pieces in FY17 to about 2.25 lakh pieces in FY23. But new currency has not halted counterfeiting, as over 91,000 fake 500 rupee notes and over 9,800 fake 2,000 rupee notes were detected in FY23.

There’s no real way of verifying if the note ban hurt terror funding, but the horrifying Pulwama massacre of 2019 and terror acts after it, suggest that the impact was temporary.

Disruptive events, however, do spark behavioural changes in citizens. This helped demonetisation deliver some unintended long-term wins for the economy.

Financialisation of savings: With property transactions frozen and a forced influx of cash into bank accounts, demonetisation provided the initial trigger for households to switch from physical to financial assets. RBI data show investments in shares and mutual funds jumping from under ₹30,000 crore in FY16 to ₹1.74 lakh crore in FY17, never to look back. Along with financial savings though, demonetisation also seems to have forced households to rely more on borrowings. Financial liabilities, which were at less than ₹4 lakh crore in the five years to FY16, rose to ₹7.5 lakh crore by FY18 and have risen further since. This suggests that the rebound in consumer confidence after disruptive events may not have been matched by reviving income.

Digital adoption: Rapid digital adoption has been one of India’s success stories this past decade. Demonetisation probably sowed the seeds of this success, with transfers via NEFT and IMPS shooting up by 117 and 43 per cent respectively in FY18. UPI transactions recorded their first significant volumes of about ₹1 lakh crore in FY18.

Tax compliance: It is not clear whether demonetisation did the trick. But the note ban certainly put the Tax Department into overdrive on issuing demand notices on high-value transactions. This, coupled with the requirement of PAN-Aadhar linking and cross-matching of GST data, has worked to make tax avoidance a complicated affair for ordinary folk. This has led to a consistent rise in IT return filings and contributed to buoyant personal tax collections.

Published on March 26, 2024

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.