In comparison to the economic, financial and monetary tsunami that swept across India on November 9, 2016, the RBI’s notification of May 19 on the recall of ₹2,000 notes was akin to just a strong wave hitting one shore. The reasons are obvious.

The ₹2,000 notes comprised only about 10 per cent of the total currency as of end-March 2023; in comparison, 86 per cent of currency was demonetised in November 2016. Further, the time for the public to turn in their old notes is much longer now — about 20 weeks versus five weeks then.

However, the main reason for the negligible impact of the May 19 notification is the extraordinary escape clauses that followed. SBI, the very next day, issued a circular stating that no ID proof was required for exchange or deposit of the ₹2,000 note. To cap it all, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das on May 22 announced that the notes will continue to be legal tender after September 30.

The ₹2,000 note was originally issued right after the note ban was announced to replenish the drastically depleted stock of currency as fast as possible. Since the goal of the ban was to reduce the scope for black money by removing high denomination (value) notes, was not doubling the size of the highest note (₹1,000 back then) aggravating the malaise? The answer is not so clear-cut.

Granted that the note ban was avoidable. But the subsequent issuing of the ₹2,000 note was helpful in replenishing the drastically depleted stock of currency. Critics of the ₹2,000 note could retort: then why not a ₹5,000 or ₹10,000 note instead? They do have a valid point.

However in making concrete, quick decisions in real time, the line has to be drawn arbitrarily somewhere. One can conclude that the ₹2,000 note perhaps struck the right balance between faster replenishment and avoiding too high valued notes.

As the dust was settling on the trauma of demonetisation, the next logical step would be to phase out the ₹2,000 note. This is what the RBI has been doing. From its peak of 33,632 lakh in March-end 2018, the number of ₹2,000 notes kept steadily falling to 21,420 lakh as of March-end 2022.

In value terms, from a peak of 50 per cent in March 2017, the share of ₹2,000 notes has steadily fallen to about 10.8 per cent of total currency by end-March 2023. Even without these data, one could notice that ₹2,000 notes were hardly in circulation. ATMs stopped dispensing them quite some time back, and banks are reluctant to provide them to customers.

What was unwarranted is the purported justification in the notification for recalling the notes. Item # 2 states that “about 89% of the 2K banknotes were issued prior to 2017 and are at the end of their estimated life span of 4-5 years.” It then goes on to say “it has also been observed that this denomination is not commonly used for transactions.”

These two statements contradict each other. If these notes are not used much, they will get less soiled and should last, presumably, longer than 4-5 years. Even if the RBI’s estimated lifespan is taken as accurate, since most of the ₹2,000 notes were printed by end-March 2017 and the small remainder (2.5 per cent) by end-March 2018, the bulk should have been disintegrating or getting dirty and, therefore, returned to RBI for exchange by end March 2022 itself. Hence, and some have also pointed out, why not wait a bit more until the ₹2,000 notes are almost extinct?

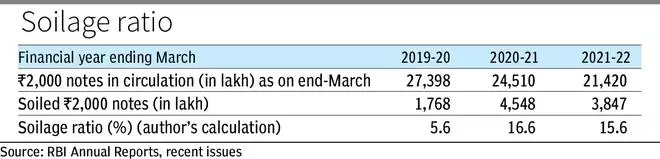

From the RBI data (see Table), the soilage ratio — the percentage of notes at the end of last financial year that were disposed of during the current year — can be computed. For instance, there were 24,510 lakh notes at March-end 2021, and 3,847 lakh of these were disposed of during FY 2021-22 — that is, soilage ratio of 15.6 per cent for this period.

As the stock of notes — mostly issued in 2017 — gets older, the soilage ratio goes up. This was seen in FY 2019-20 and FY 2020-21. However, in FY 2021-22, the spoilage ratio has fallen marginally to 15.6 per cent. In the fifth year of their life, if only about 15 per cent of existing notes are spoiled, that implies the lifespan is likely to be considerably more than the RBI’s estimate of 4-5 years. Members of Parliament should ask the RBI how exactly it came up with this estimate.

Lifespan estimation

Estimating the lifespan from the soilage ratio is useful only if the stock of notes is unchanged. That is the case for the ₹2,000 note. When new notes are issued to meet the growing demand for currency and also to replace soiled notes, the computed soilage rate for a mix of old and new notes is not a reliable guide to their lifespan.

Other factors will also affect the soilage ratio, such as the ease with which RBI accepts existing notes and provides new notes in return. Without in-depth knowledge of the process, which only RBI and commercial bank officials working in currency management have, one cannot and should not make any generalisations.

Leaving aside the legal and logistical issues, one thing is clear. The RBI’s justification that the withdrawal of the ₹2,000 note is in accordance with its Clean Note policy is dubious. Instead, it should have stated upfront that its goal is to reduce black money (actually untaxed income or wealth).

Reducing high value notes and digitising the payments system are sound means towards achieving this goal. In short, the RBI should come clean regarding the motivation for this notification.

The writer is Distinguished Professor, St Joseph’s Institute of Management, Bengaluru

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.