Apparel form a big chink of Vietnam’s exports to the US | Photo Credit: LINH PHAM

The government of Vietnam is among the many that have rushed to negotiate trade concessions following the announcement by US President Donald Trump of a 90-day pause on the reciprocal tariffs imposed on them, on top of a base 10 per cent tariff hike. There is no way the country, like many others, can absorb the proposed 46 per cent hike in imposts and stay on its current growth and development trajectory.

There is one difference, however. Vietnam is, along with China, one of two countries in Asia that made the transition from a largely state-led and centrally coordinated growth path with minimal dependence on Western markets, to one that is market friendly and export oriented. Like China, it also managed to ensure rapid growth averaging upward of 6.5 per cent per annum for almost four decades since it launched on reforms in 1986.

Crucial to that success in both countries has been a rapid increase in manufactured exports to Western markets. The result has been a significant increase in per capita income and huge reductions in poverty.

Yet, while China, having followed a similar trajectory, chose to stand up to the US and retaliate with tariffs on imports from that country, Vietnam seems eager to avoid any confrontation. It has in fact rushed to start negotiations and offer any concessions it can to placate the Trump administration and stall the tariffs imposed on its exports to the US.

A longer history of central planning, an early diversification into manufacturing even before reform, the technological capabilities that endowed the system, and the benefit of a large domestic market because of its geographical size and large population are important factors explaining China’s response.

By contrast, the relative weakness of Vietnam could be explained by the nature of its development trajectory, the limited nature of economic diversification, and an overdependence on exports to a few markets, especially the US market.

The role of exports in Vietnam’s economic growth is evident in the rise of the ratio of goods exports to GDP, from just 3 per cent in 1986 to 60 per cent two decades later in 2006. While that ratio hovered around that level till around 2013, it rose again to cross 90 per cent in 2022, before settling at 82 per cent in 2023.

That reflects the huge dependence of the country on exports. One redeeming feature has been the nature of those exports, with the share of manufacturing in the total rising from around 71 per cent in 2000 to 90 per cent in 2020. Vietnam has moved out of dependence on primary product exports.

However, these aggregate figures conceal some disquieting trends. To start with, despite the many years of export market engagement and success, Vietnam’s exports are characterised by a high degree of concentration by destination.

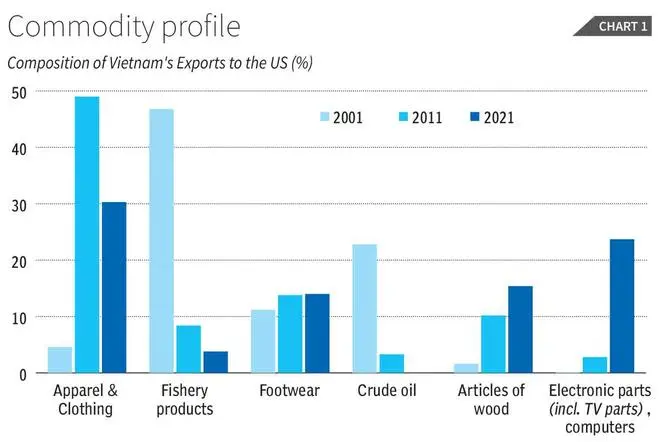

Two countries, the US (28 per cent) and China (20 per cent) accounted for as much as half of the exports from the country, even in 2023. Within exports to the US, which is threatening punitive tariffs, the commodity-wise composition also reflects concentration and unusual changes (Chart 1).

In 2001, exports to the US were dominated by Fishery products (46.8 per cent), Crude oil (22.8 per cent) and Footwear (11.2 per cent), which together accounted for more than 70 per cent of exports to that country. That is, primary products and traditional manufactures dominated. Interestingly Apparel and clothing accounted for less than 5 per cent of exports that year.

By 2011, Apparel and clothing exports came to account for 49 per cent of the total and Footwear for another 13.8 per cent. Together with Articles of wood (10.2 per cent), this set of three commodity groups accounted for 73 per cent of exports.

Meanwhile, the share of Fishery products fell to 8.4 per cent. Despite diversification, commodity-wise export concentration continued. This was the case in 2021 as well, when Electronic parts and Computers accounted for 24 per cent of exports, with Apparel, Fishery and Wood articles together accounting for another 60 per cent.

Diversification was accompanied by persisting concentration, as far as exports to the US are concerned. It is these exports that Vietnam will have to protect from the potential ravages of the Trump tariffs.

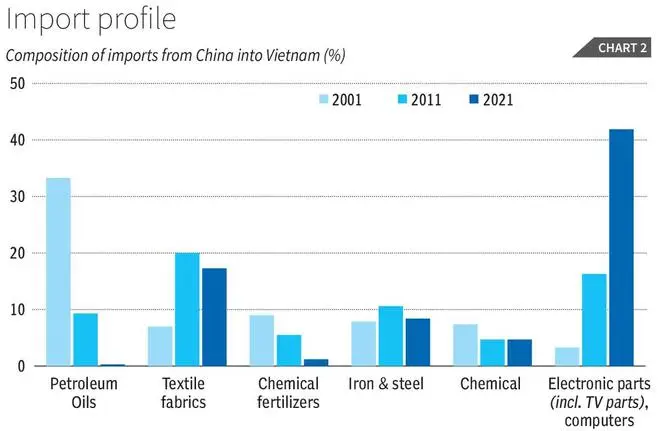

But this is not the only cause for concern. The other issue is that, while China is the second most important export market for Vietnam (20 per cent in 2023), it also is the principal source of imports. China accounted for 22 per cent of imports followed by South Korea (8.75 per cent) at a distant second. The noteworthy feature is that these imports, as well as those from elsewhere, were crucial inputs in export production.

This comes through from the composition of imports (Chart 2). In 2001, Petroleum oils accounted for a third of imports into Vietnam from China. These were likely being re-exported with limited processing.

In 2011, in tandem with the rise in apparel exports, imports of Textile Fabrics accounted for 20 per cent of imports from China, and that figure remained at a significant 17 per cent in 2021 as well.

Over these two decades, the share of Electronic parts and Computers in total imports from China rose from 3.3 per cent (2001), to 16.3 per cent (2011) to 41.9 per cent in 2021. Vietnam’s exports success was based on its plugging into value chains and serving as an export platform for goods processed or assembled based on imports of intermediates (and capital goods and technology) from abroad.

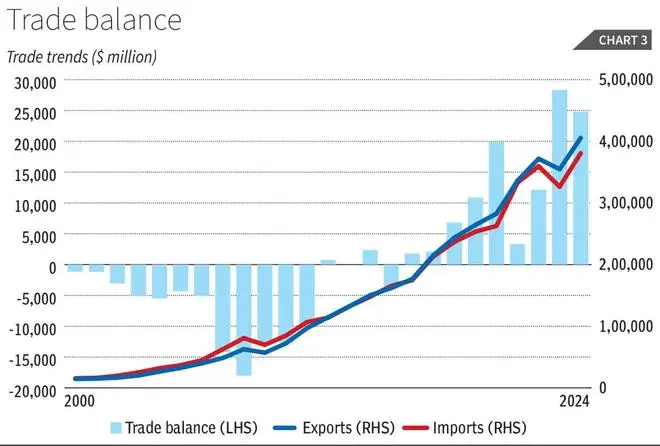

One consequence was that Vietnam’s exports and imports moved in tandem, with export success not leading to a positive trade balance till 2013, and the trade surplus even after that being small (Chart 3).

Serving as an export platform for finished goods based significantly on imported intermediates and capital goods for growth implies that sustaining a high level of exports is crucial, to ensure that the total (even if not per unit) of domestic value added is large enough. Given the importance of the American market to Vietnamese exporters, this would mean that the volume of exports to that country from Vietnam must remain high.

This explains Vietnam’s eagerness to come to a deal with the Trump administration. But the issue remains as to what Vietnam has to offer to placate the US. Tariff reduction cannot be a solution.

As part of its market-friendly, export-oriented strategy Vietnam has (especially following WTO membership) already reduced tariffs substantially. Weighted mean tariffs on imports into Vietnam have fallen from a peak level of 19.2 per cent in 1999 to a low of 2.07 per cent in 2022, with the corresponding figures for Manufactures being 16.6 per cent (2001) and 0.8 per cent (2022), and for Primary products 28.3 per cent (1999) and 2.0 per cent (2022). That is little room left for further reduction (Chart 4).

So, if negotiation is likely to work, Vietnam would have to offer major concessions in the services areas including in financial services, in which the US sees itself as competitive. But that would result in the entry of foreign banking and financial firms and inflows of financial interests and capital that can significantly increase fragility. Excessive export dependence clearly has its costs.

Published on April 14, 2025

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.