It has long been known that the very wealthy are able to shift their assets abroad and stash them away in tax havens and other jurisdictions. There are various reasons for doing this: to hide ill-gotten gains, to avoid or evade taxation, to insure against currency depreciation and otherwise hedge bets about likely economic performance in India. Much of this knowledge, however, was just based on anecdotal evidence or the occasional release of data provided by leaks like those of the Panama Papers.

Now, however, we finally have more systematic attempts to measure and assess the extent of such illicit financial flows, thanks to important work done by the EU Tax Observatory. The just-released Global Tax Evasion Report 2024 is based on a major international research collaboration building on the work of more than 100 researchers across the world. It provides a treasure trove of information and estimates at global, regional and country level, based on new methodologies that allow for annual estimates of such illicit financial flows.

This is enabled by the availability of new data resulting from some positive policy initiatives of the recent past, on the offshore wealth of households (from the automatic exchange of banking information) and on the activities of multinational companies (from the country-by-country reporting of sales and profits).

The Report has important conclusions at the global level. The overall reduction in individual offshore financial wealth has come about because of the exchange of banking information, which has enabled countries that have the information and that wish to do so, to crack down on such offshore wealth.

Indeed, the unreported proportion of offshore financial wealth has come down from an estimated 90-95 per cent in 2007-08 to around 30-40 per cent currently.

Offshore assets

However, new forms of offshore assets are emerging and becoming significant, such as real estate. Also, corporate tax evasion through mispricing across subsidiaries to shift profits to low tax or no tax jurisdictions, continues apace and has even ballooned in recent years, despite (or perhaps because of?) the rather weak efforts of the OECD.

But here we focus on what the Report tells us about offshore wealth held by Indians.

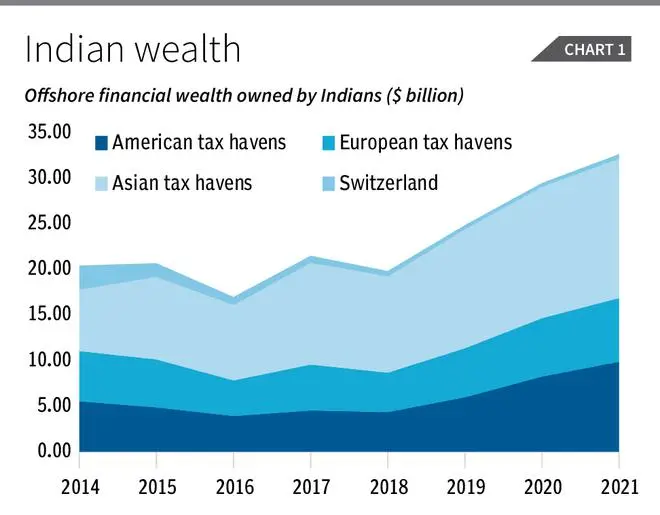

Figure 1 provides estimates of the total offshore wealth held by Indian residents in some major tax havens. This is calculated using a methodology developed by the French economist Gabriel Zucman (a co-author of this Report) which uses the anomalies in international investment positions across different countries.

Essentially, when individuals own portfolios of financial securities — stocks, bonds, mutual fund shares — offshore using intermediaries, these holdings cause anomalies in international investment statistics. For example, when an Indian resident holds US stocks through a Swiss bank account, this is not recorded as an asset held in India, or in Switzerland (where the net position is zero) but it is recorded as a liability in the US. This is why, globally, financial liabilities are greater than assets. Zucman showed that this discrepancy can be used to estimate the extent of offshore wealth held in different jurisdictions.

The data in Figure 1 are calculated by multiplying the estimates in the Report (which are provided as shares of GDP) by the GDP estimates for India (in US dollars) of the World Bank. The results are startling. Far from declining (as it has done in much of the rest of the world, largely because of the exchange of banking information making it harder for the rich to evade taxes) offshore wealth holding has increased quite significantly in absolute terms after 2018.

Rising trend

Between 2018 and 2021, the amounts held in just these jurisdictions went up by $12.8 billion, from $19.8 billion to $32.6 billion. This fits in with the perception that economic growth in India has disproportionately benefited the rich, who have also therefore increased their illicit transfers out of the country.

The changing direction of these flows is also worth noting. It turns out that Switzerland was not really an important final destination; rather, it has probably been more of a conduit to holding financial assets elsewhere. Flows to both American and European tax havens have increased, but the really notable increase in the recent past has been to Asian tax havens, such as the UAE and Singapore.

Of course, this immediately raises the question: since India is part of the system of automatic exchange of banking information, the pattern of these flows, their final destination and the holders of these assets, must all be known to the Indian tax authorities. So why is more not being done to track these, check on the holders, and at the very least force them to pay taxes at least on the returns from these assets?

The same organisations that are now kept so busy with imposing multiple cases against political Opposition leaders and dissenters of the current government would do well to take up the direct examination of such financial wealth held abroad, which is in fact damaging to India’s economy.

Real estate wealth

In addition, a significant amount of offshore wealth is now shifting to being held in the form of real estate. The researchers have delved into those locations that actually do provide ownership data on real estate. Figure 2 describes the results for Indian wealth holders, and Dubai emerges as the top destination for such assets, followed distantly by Singapore and London.

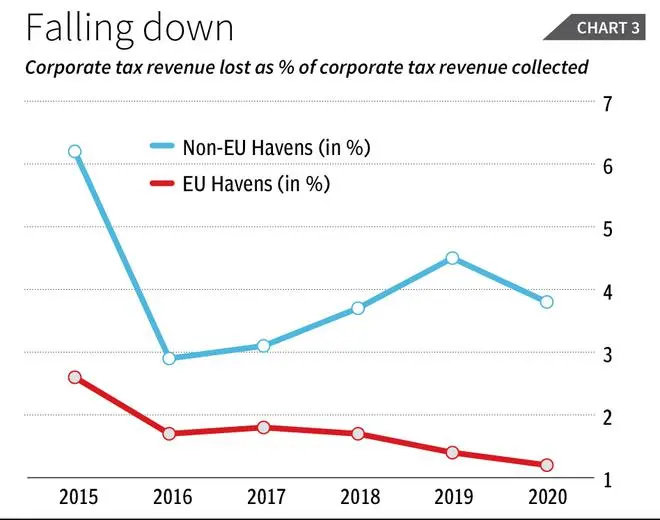

The one area in which the Indian government appears to have been slightly more effective is in terms of reducing the tax avoidance by multinational companies, which appears to have come down since 2015 — possibly because of the institution of the turnover tax on sales of global digital companies (Figure 3). However, the significance of non-EU tax havens in such profit shifting remains high.

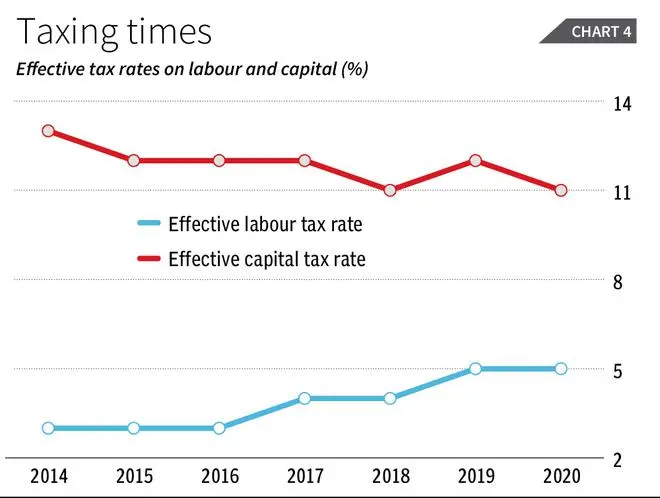

Another reason could simply be that the effective tax rate on corporations has actually fallen within the country, so that there is less reason for companies to shift their profits out.

Figure 4 indicates that the effective tax rate on companies has fallen from 13 per cent in 2014 to 11 per cent in 2020, even as the effective tax on labour incomes rose from 3 per cent to 5 per cent. It is unfortunate that in a country with such high income and asset inequality, the tax regime is also effectively becoming more regressive.

It is also the case that it is increasingly possible for the very rich to hold assets within the country without being taxed by utilising various loopholes and because of inadequate requirements to reveal beneficial ownership of shell companies and trusts.

The Report identifies many strategies, at national and international level, to address these concerns. But clearly, such policies can only be undertaken with political will to do so. We have to see whether the Indian government will actually do something about such tax evasion by the wealthy, rather than just talking about it.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.