India is the second largest edible oil market in the world. It consumes, on an average, 21 million tonnes (mt) of edible oil each year, of which, 7-8 mt are produced locally, while 13 mt — that is, 66-68 per cent — are imported. This makes India the No.1 importer, with close to $18 billion outflow last year.

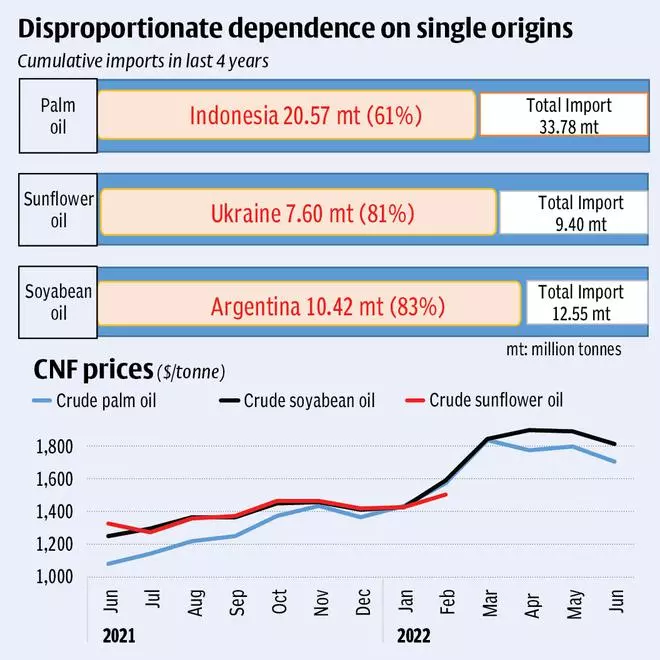

According to a 2018 Rabobank report, the annual consumption of edible oil is set to cross 34 mt by 2030, which would require import of almost 25 mt. The estimated 73 per cent dependency on imports makes it a food security concern. And what makes matters worse is that we are dependent disproportionately on individual countries.

This skewed dependence reared its ugly head recently: first, the Russia-Ukraine war stopped sunflower oil flows from Ukraine, and this was followed by Indonesia’s ban on palm oil exports. A price rally of more than 50 per cent followed, impacting both the industry and the consumers.

The industry battled with price volatility and increased working capital requirements, while keeping the plants running with paltry supply from alternative origins. Hence an integrated approach is required to tackle these issues on an immediate and long-term basis.

The topmost priority should be to finalise win-win agreements with countries and trade blocs that can grow as alternative supply sources — for instance, Malaysia for palm oil and Mercosur nations for soyabean and sunflower oils.

Bilateral FTAs (free trade agreements) are easier to undertake than multilateral ones. A staggered approach, ensuring food security first and then adding other items later, could help achieve faster outcomes.

Focusing on increasing domestic production is paramount, and the Oil Palm Mission launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi is laudable. A definitive start towards self-reliance, it is intended to yield 1.1 mt by 2026 and 2.8 mt by 2030. States must execute the submitted proposals on priority basis and any additional policy support needed to fast-track sizeable investments into upstream palm plantations should also be provided. This will be a big enabler in increasing the scale of locational output and attracting investments into the processing and supply chain.

The second building block

With 10-12 per cent of the projected 2030 imports taken care through the Oil Palm Mission, the possibilities of augmenting local supply through other high oil-yielding oilseeds must be studied. Mustard is one of those which has the potential to grow, both in terms of demand and supply.

It is amongst the top two preferred oils in the upper half of India, which accounts for more than 50 per cent of our population. Post-Covid, the consumer pull has increased further as mustard is believed to be a healthier oil. Pre-Covid, the average consumption was 2.413 mt with CAGR at 0.4 per cent, while post-Covid it increased to 2.735 mt — a 13 per cent growth. Even though other aspects contributed to this change, it still makes a strong case for its ability to snatch market share from imported oils. On the supply side, it requires lesser water as compared to wheat, is resilient enough to grow in a wide range of soil and weather conditions and, lately, its farm margin vis-à-vis wheat has also increased. These are attractive factors for the farmer to cultivate the crop — and the momentum is already there — but assured procurement and cluster-based localised processing also need to be provided to the farmers to diversify. Also, a consistent duty regime on imported oils, from planting to harvest, will give assurance and forward price visibility to farmers.

There is enough headroom for acreage expansion as mustard currently accounts for about 10 per cent of the rabi crop acreage. To accelerate the process, planting of genetically modified mustard seed developed in India by our scientists must be allowed.

This will give an immediate fillip to its adoption and yields, boosting farmers’ income and triggering increased acreage and production.

After the adoption of BT Cotton seed, India managed to double its yields, producing enough for our increasing needs and a surplus for exports. Post Bollgard I, the average yield moved up to 320 kg/hectare (2002-07) from the 229 kg/hectare average of the previous decade. And then with Bollgard II, the average yield jumped to 455 kg/hectare (2007-21). These yields coupled with the adoption levels and acreage expansion led to output jumping from 2.3 mt to 5.3 mt in two decades. Today, annually the country produces double that of in 2001, aided by a mere 17 per cent increase in acreage.

The upside potential

While model farms show promise, our estimates indicate that with conventional seed mustard production can increase from 12 mt to about 16 mt by 2032-33, that is, a healthy 33 per cent jump. But the growth can be much steeper with GM Mustard.

If allowed, the current 9.1 million hectares under mustard can increase at a CAGR of 3 per cent reaching 12.2 million in 10 years. This 3 million hectares may seem high but is feasible as mustard occupies just 10 per cent of the overall rabi acreage of 62 million hectares and will just need a 5 per cent acreage shift.

On the yield side, GM Mustard can increase at a CAGR of 4.5 per cent to go up to 2.33 tonnes/hectare. Haryana achieved 2 tonnes/hectare for two consecutive years from 2018-20 using conventional seed; with GM Mustard seed the yields can be raised further, even at the national level. Thus, India has the potential to produce 28.5 mt of mustard seed in 10 years, adding 6.6 mt of incremental oil to the current base of 4.6 mt, thereby reducing our import dependence by 26 per cent and saving around $9.3 billion on the import bill.

The Oil Palm Mission and BT Mustard together can potentially add 9.6 mt more, thereby doubling our current production of 8 mt. The introduction of BT Mustard merits consideration, especially if it is going to bring down import dependence from 75 per cent to about 45 per cent in 10 years.

The writer is a top executive of an MNC dealing in agro commodities, including edible oil

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.