Infosys co-founder N.R. Narayana Murthy recently stated in a podcast that India has one of the lowest productivity rates in the world and suggested that the country’s youth should consider working 70 hours a week to bolster the nation’s growth and development.

But the data shows that Murthy is wrong on several counts.

The most hardworking workforce

India ranks 7th globally in terms of average weekly working hours, with employed individuals dedicating 48 hours a week to their jobs, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) data as of April 2023. The UAE tops the list of countries where workers work the longest, with 52.58 hours per worker in a week. It is followed by Gambia, Bhutan, and Lesotho.

Indians seem to be extending average working hours, not just in India but in other countries too. A significant proportion of the population in the UAE and Qatar comprises Indians, which are among the top 10 on the hardworking list. Approximately 30 per cent of the UAE’s population and 25 per cent of Qatar’s are of Indian origin.

A research paper published in the Harvard Business Review, titled ‘Extreme Jobs: The Dangerous Allure of the 70-Hour Workweek,’ shows that the surge in working hours observed in developed nations, such as the United States, can be partially attributed to the economic advantage gained from the availability of the Indian and Chinese work force.

Working hours and productivity

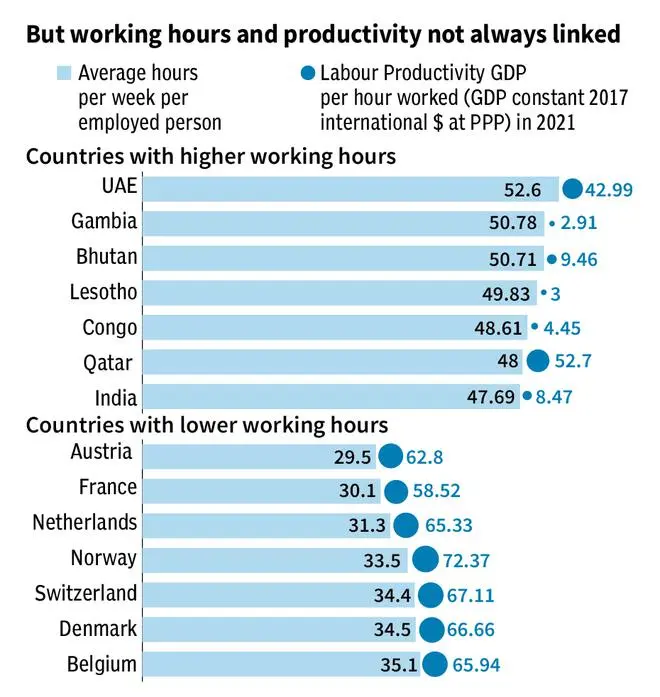

Murthy’s statement does draw attention to a critical issue—the declining productivity rate in India. CEIC data shows that India’s labour productivity has dropped from 9.1 percent in 2016 to 2.5 percent in 2022. But India’s predicament is not due to fewer working hours, for data shows that there is little correlation between working hours and productivity.

Countries that are among the top 10 in clocking long working hours, such as Gambia, Bhutan, Lesotho, and the Congo, have very poor productivity. Countries such as the UAE and Qatar have managed higher productivity with longer hours due to the massive capital investments made by these countries.

On the other hand, countries such as Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and Switzerland, known for their low working hours and great work-life balance, have shown stellar productivity numbers.

Germany and Japan

Murthy’s remarks about the post-World War II workforce in Germany and Japan may not be very accurate. He suggested that both nations rebuild their economies through extended working hours. However, historical data from Our World in Data paints a more complex picture. In Germany, working hours have seen a significant decline after 1951, and in Japan, they have fluctuated over a ten-year period, showing no direct correlation between working hours and economic prosperity.

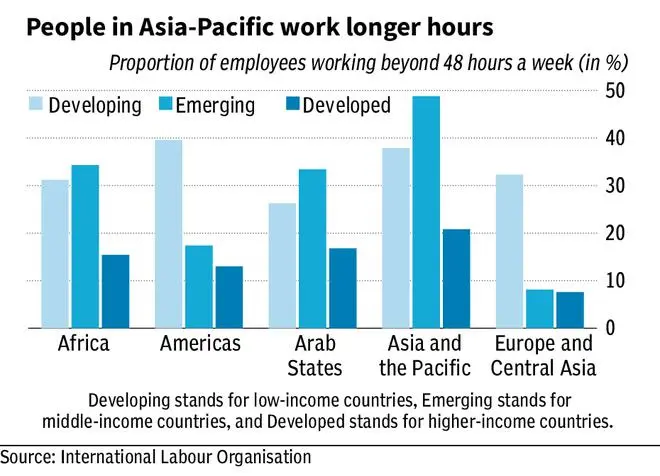

The rise in extended working hours seems concentrated in Asia-Pacific, Africa, and the Arab States, with employees in these regions working more than 48 hours a week, a phenomenon driven by the pursuit of economic growth and development. India, classified as a lower-middle-income economy, finds itself competing in this race to achieve significant economic advancement. However, it’s imperative to question whether the escalation of working hours necessarily leads to positive outcomes.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.