The reorientation of economic prowess across the world results from various forces such as history, technological innovation, market capture, labour migration, or country dynamism. Are we currently looking at a reorientation of economic power?

If we measure the GDP of various countries at PPP (purchasing power parity), an interesting pattern emerges over the period 1980-2019 (i.e., the pre-Covid years). The IMF’s country classification in its publication World Economic Outlook divides the world into two major groups: advanced economies (AEs) and emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). Out of the 191 member countries of the IMF, 41 are classified as AEs, rest of the countries, irrespective of their size or location, are classified as EMDEs.

Several stylised facts emerge from Table 1. The share of AEs experienced a secular decline from around 63 per cent of global GDP in 1980 to around 43 per cent in 2019; meanwhile, the share of EMDEs has increased from 37 per cent to 57 per cent – these are major shifts over nearly four decades. Within EMDEs, the share of emerging and developing Asia (i.e., Asia minus Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao, and Singapore) has experienced more than a three-fold rise during this period.

This increase, admittedly, is the story of the emergence of East Asian tigers and cubs (since the 1970s), China (since the 1980s), and India (since the 1990s). China alone now accounts for around 18.5-19 per cent of global GDP, while the share of India is around 7-7.25 per cent. Regrettably, the share of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa remained low at about 3 per cent.

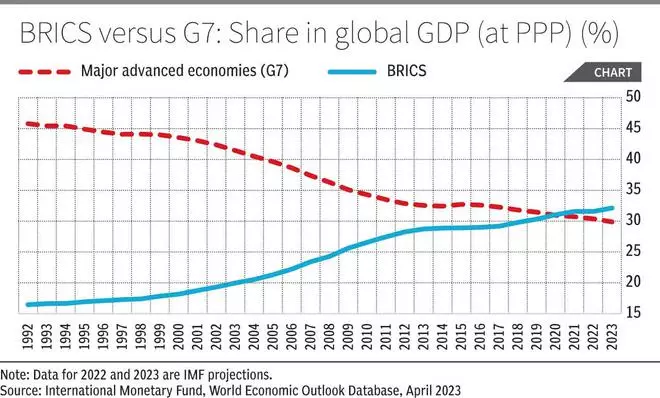

More interesting country groups exist, however. For example, the share of the major advanced countries (i.e., the G-7 bloc comprising the US, Canada, the UK, France, Germany, Italy and Japan) had come down from around 50 per cent to 30 per cent over these four decades.

Brics rise

In contrast, the share of the BRICS (i.e., Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) has not only increased at a spectacular pace, but it has also surpassed the share of G-7 countries by 2020 (Figure 1). That is to say, despite the lack of homogeneity among the BRICS bloc, it has emerged as the most powerful bloc of global economic power since 2020!

How far are these numbers at PPP valid? There is an interesting controversy regarding how to compare the GDP among countries. Two notions of GDP are typically arrived at – one at market exchange rate (MER) and the other at purchasing power parity (PPP) (see table 2). Incidentally, at MER, China’s GDP is about 42 per cent of the combined GDP of the G-7 countries. However, the market exchange rate may not reflect the differences in the costs of living indices across the countries. For this purpose, the notion of Purchasing-power-parity (PPP) is used.

The PPP conversion rate between two countries is “the rate at which the currency of one country needs to be converted into that of a second country to ensure that a given amount of the first country’s currency will purchase the same volume of goods and services in the second country as it does in the first” (IMF).

In the IMF database, typically, it is expressed as local currency per US dollar. Such PPP conversion rates are outcomes of price comparisons across countries based on the International Comparisons Program (ICP) by a consortium which includes the IMF and the World Bank. If we use this conversion factor, viz., 21.1 (row 3 of Table 2), then India’s GDP at PPP is arrived at $9.5 trillion!

MER vs PPP

What is preferable? GDP at MER or GDP at PPP? For measuring the absolute size of an economy, it is preferable to take GDP at MER, which is what is normally done. But often, for comparison purposes, GDP at PPP is used. If we add up the GDP at MER across G-7 countries and across the BRICS bloc (all in dollar terms), while the GDP of G-7 countries was 12 times that of BRICS GDP in 1980, it is only 1.6 times now! The story of a reorientation of economic prowess holds.

The rapid rise of larger developing countries as growth leaders have profound implications for the global economy and geopolitics. China’s rise as a possible counterweight to the US is changing many global equations in economic and political spheres. India is gaining importance in various international and multilateral fora, by its own right.

However, it might not be an exaggeration to say that contemporary global power is not yet aligned with the changed economic reality. Specifically, the global architecture is still following the old economic reality. It is an opportune moment for such issues to be brought to the agenda of the high table in G-20 or BRICS.

Ray is Director of the National Institute of Bank Management, Pune and Pal is a Professor of Economics at the IIM, Calcutta. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.