In her Budget speech, the Finance Minister claimed that the centre pieces of the Budgets for both the current financial year (2021-22) and the next (2022-23) are sharp increases in capital expenditure driven by enhanced public investment. That expenditure would not only strengthen infrastructure in seven areas (Roads, Railways, Airports, Ports, Mass Transport, Waterways, and Logistics Infrastructure), she argued, but have multiplier effects that would crowd in new private investment and raise the rate of growth.

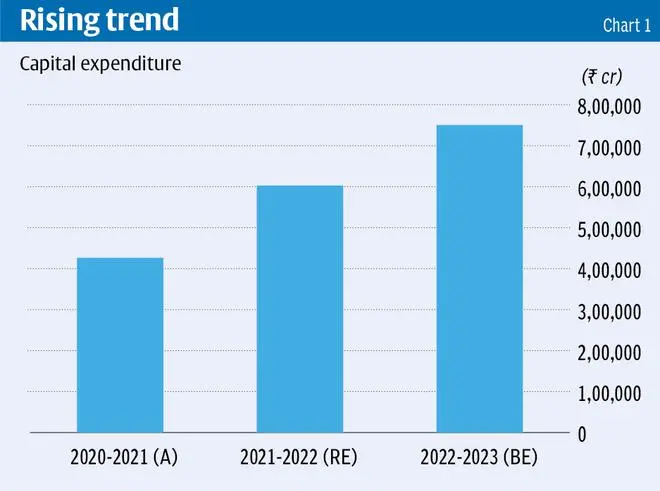

According to figures in the Budget, capital expenditure did increase by 41 per cent from ₹4.3 lakh crore in 2020-21 (actuals) to ₹6 lakh crore in 2021-22 (RE) and is slated to rise by 24.5 per cent to ₹7.5 lakh crore in 2022-23 (Chart 1). Clearly, the Finance Minister was not happy with even this projected increase and compared the Budget estimate for 2021-22 (₹5.5 lakh crore) with the Budget estimate for 2022-23 to claim that she had actually provided for a 35 per cent increase in capital expenditure, which is not true.

But even if we stick with the actuals, revised estimates and Budget estimates, the rise in capital spending in both 2021-22 and the proposed increase in 2022-23 are quite significant, and surprising coming from an administration that over its last and current term embraced fiscal conservatism and showed a reticence to spend even in the midst of the Covid-19 induced crisis.

Breaking down the numbers

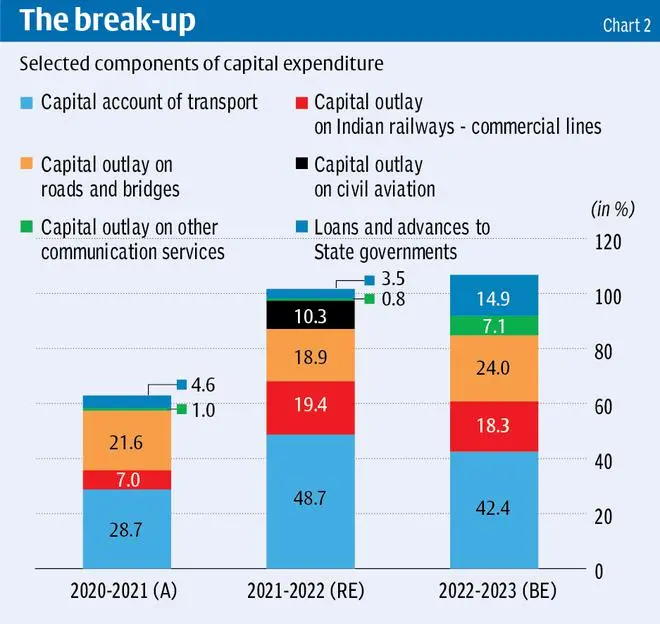

However, a closer look at the breakdown of this expenditure reveals a number of important features. The first is that in both high capex spending years, capital outlays for the Transport sector account for a dominant share of capex spending— 48.7 per cent in 2021-22 and a proposed 42.4 per cent in 2022-23 (Chart 2).

Allocations under the capital account of the Transport sector rose from ₹1.2 lakh crore in 2020-21 to ₹2.9 lakh crore in 2021-22 and are projected at ₹3.2 lakh crore in 2022-23. These sharp increases have been financed with the high duties and cesses the Centre has imposed on petroleum products. Receipts from the special excise duty on motor spirit rose from ₹79,359 crore in 2020-21 to ₹92,970 crore in 2021-22 (RE) and are budgeted to touch ₹95,750 crore in 2022-23. The corresponding figures for a cess on crude oil are ₹10,894 crore, ₹17,500 crore and ₹18,020 crore; and for the road and infrastructure cess on petrol and diesel ₹1,23,596 crore, ₹2,03,235 and ₹1,38,450 crore respectively.

Receipts from these cesses accrue to the Central Road and Infrastructure Fund (CRIF), which was brought under the Ministry of Finance in July 2018. This has allowed the Finance Minister to squeeze out revenues using these inflationary taxes and allocate them for capital spending in a range of areas, but especially for roads and highways and the railways. Capital outlays for commercial lines of the Indian Railways rose from ₹29,990 crore in 2020-21 to ₹1 1.17 lakh crore in 2021-22 and is projected to rise to ₹1.37 lakh crore in 2022-23. In each of those years, the capital expenditure of the Railways met with resources from the CRIF amounted to ₹60,398 crore, ₹49,800 crore and ₹52,700 crore respectively.

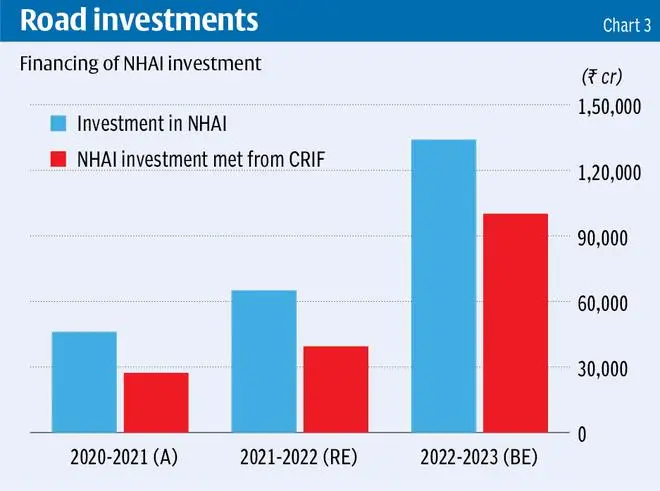

A similar situation applies to the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI). Investment in the NHAI rose from ₹46,061 crore in 2020-21 to ₹65,060 crore in 2021-22 and is budgeted to rise to ₹1.34 lakh crore in 2022-23. The share of this financed with resources from the CRIF is placed at ₹27,300 crore in 2020-21, ₹39,410 crore in 2021-22 and a projected ₹1 lakh crore in 2022-23 (Chart 3).

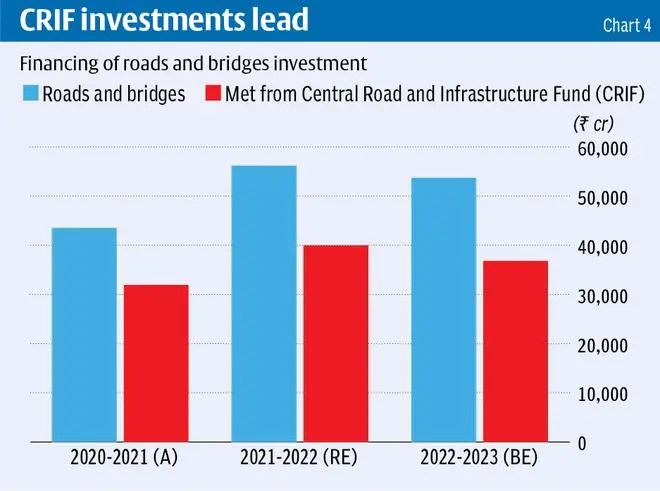

Finally, investment in roads and bridges outside of the NHAI is estimated at ₹43,498 crore, ₹56.166 crore and ₹53,695 crore in 2020-21, 2021-22 and 2022-23, with the part met from the CRIF amounting to ₹31,928 crore, ₹39,987 crore and ₹36,819 respectively (Chart 4). In sum, to the extent that there is an infrastructure push reflected in the Budgets for 2021-22 and 2022-23, it is restricted to a very few areas and rides on the imposition of burdensome inflationary taxes on universal intermediates like petrol and diesel.

Burdensome taxes

Besides this narrow and regressive nature of the public investment agenda of the government, there are certain large expenditures undertaken in 2021-22 or proposed in 2022-23 that cannot really count as central capital expenditure in any material sense. Thus, in 2021-22, the government set aside a sum of ₹62,114 crore (or more than 10 per cent of capex that year) for the Ministry of Civil Aviation to be transferred to Air India Asset Holding Limited “for servicing of loan transferred to SPV as a result of financial restructuring of Air India.” This was effectively a provision to write of a large chunk of Air India’s debt prior to its sale to the Tata group.

Finally, in the projections for 2022-23, the capital expenditure figure quoted by the Finance Minister includes ₹1.12 lakh crore of loans to State governments. This possibly reflects the last tranches of the back-to-back borrowing and lending that the central government agreed to engage in, as a substitute for the promised compensation for shortfall of GST revenues relative to a guaranteed trajectory. That compensation scheme expires in July this year. The service payments for this debt are to be met by extending the term of the GST compensation cess beyond the period when it was used to support the States. This is definitely not capital spending by the Centre and is unlikely to be used fully even by the States to finance capital spending.

One other provision in the Budget for 2022-23 that is intriguing is a capital allocation of ₹53,033 crore to “other communications”. Much of this (around ₹47,000 crore) is an infusion of capital into public sector BSNL to restructure the company and upgrade its 4G capabilities. This is indeed surprising. BSNL was stripped of much of its staff and workers under a voluntary retirement scheme, and the government did not permit it to upgrade its technology on the ostensible ground that the company needs to be privatised or liquidated.

It is unclear what has inspired the turnaround in position that the proposed allocation suggests. It could either be to revive BSNL so as to ensure a degree of competition in the telecom space now dominated by three private players. Or it might be “prior action” to improve the prospects for successful privatisation of BSNL. That would be an advanced adjustment with objectives similar to the restructuring of Air India as part of a disinvestment exercise.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.