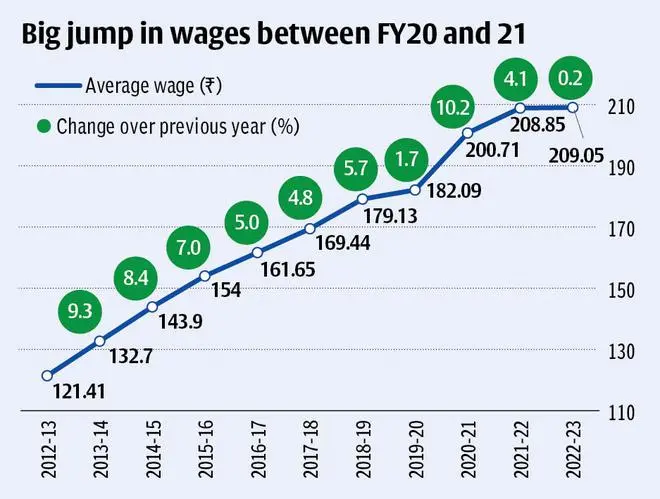

The annual increase in the average MGNREGA wages has been quite uneven. While the wages increased between 8 to 10 per cent in FY13, FY14 and FY21, the increase was a mere 1.6 per cent in FY20.

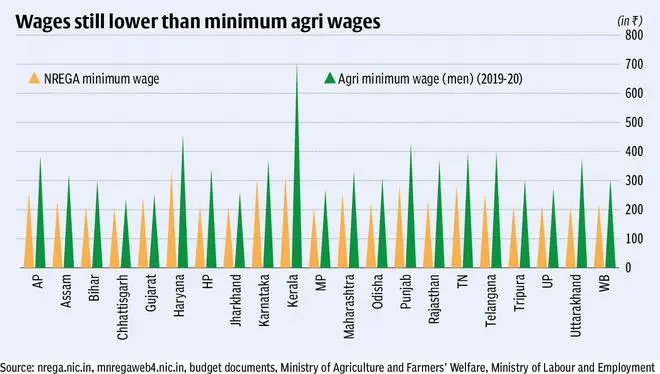

Annual increases in individual states have been higher or lower than the national average. For instance, for 2022-23, Kerala and Karnataka saw the steepest hikes of ₹20, taking their minimum wages to ₹311 and ₹309, respectively. Wages, however, remained the same for Manipur, Mizoram and Tripura. The former two, along with Haryana, are now the states that pay the highest wage for NREGA labourers, while Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh pay ₹204. At the same time, the wages in no states are at par with the agricultural wages set by their respective state governments or the National Minimum Wage of ₹375 per day.

The past, present and future

The MGNREGA was passed in the parliament on August 23, 2005., and was implemented the following year. “It aims to enhance livelihood and security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of employment in a financial year to every household,” reads its mission statement. The jobs include cleaning canals and drains, tilling, ploughing and clearing weeds.

It was decided that the NREGA workers get paid the minimum wage for agricultural labourers in the state or that the centre notifies a separate wage rate. The latter has been followed since 2009, and since then, advocacy groups have been demanding a higher wage.

Labourers across states also say that the wage isn’t enough forsurvival. “Luckily, my husband has a daily wage job. But there are families nearby that are only dependent on these wages,” says Anitha Chandran, a labourer from Kochi. Anitha has been engaged in tilling, ploughing and canal cleaning for to two years now.

According to the data available from the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, the minimum agriculture wages in states vary from ₹251 in Gujarat and ₹701 in Kerala per day. This is as of FY20. “People who take up other jobs privately, like ploughing and digging usually get an average of ₹550 a day. This is quite higher than NREGA wages. Also, our wages are not paid on time,” says Aboobacker P, an NREGA worker, until November 2021. He is now a teacher in a government school in Kerala’s Wayanad.

On the other side of the spectrum is Prakash Pipari, from Uttar Pradesh’s Sitapur, taking up NREGA jobs since 2007. Today, the daily wage that an NREGA worker earns in UP is merely ₹213, around ₹100 lesser than what a worker makes in Kerala. So naturally, Pipari laments how difficult it has been to manage his expenses. “Back in the day, we would earn around ₹60 a day. Atta and vegetables were also not that expensive back then,” he says. “However, things started getting worse over time and the current wages need to be hiked. The payment is delayed and these days, there isn’t much work, despite the rising demand for jobs,” he says.

A lifesaver during a pandemic

Is the scheme’s popularity rising? To explain that, we must go two years back in time. Before the pandemic struck, Aboobacker worked as a sales assistant in a granite store and Anitha was a packaging worker in a factory. Both places got shut permanently during the lockdown, and suddenly, the duo, like many others, saw their family’s income dwindle. That was when the two of them, located in different parts of Kerala, found themselves seeking jobs through NREGA.

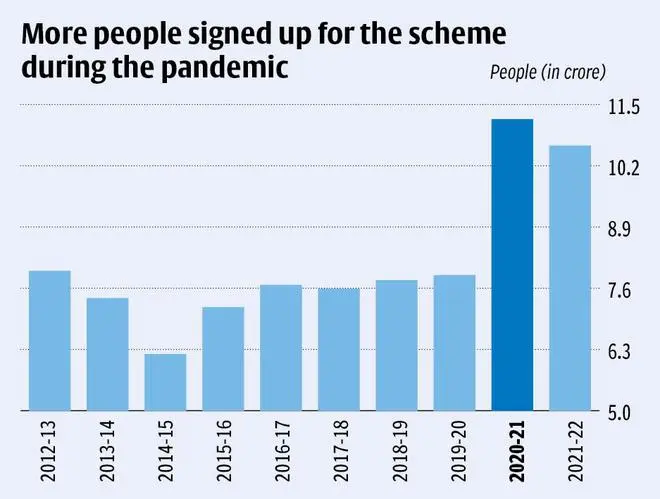

The pandemic year saw a 42 per cent growth in the number of people who took up MGNREGA jobs. According to the scheme’s portal, in 2020, the number of people who took up jobs was 11.19 crore, in contrast to 7.8 crore in the previous two years. The number went down to 10.36 crore in the last financial year; however, it is still 35 per cent higher than pre-pandemic levels.

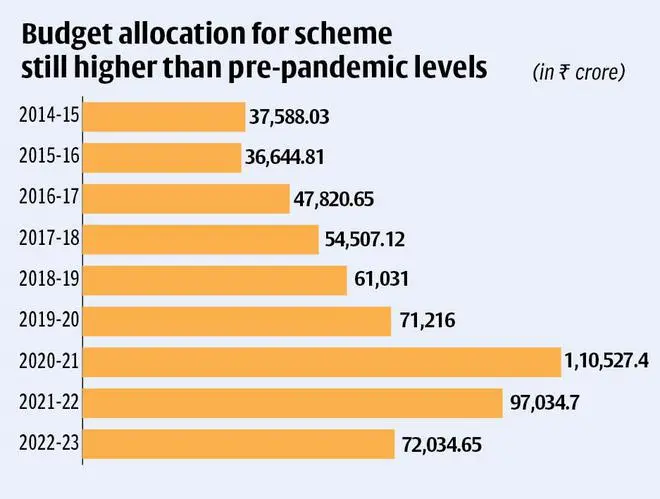

During the pandemic year of 2020-21, the scheme’s budget also went up by ₹39,311 crore to reach ₹1,10,527.4 crore. While the allocations have been slightly lower for the consecutive financial years (₹97,034.7 crore and ₹72,034.65 crore in FY22 and FY23, respectively), they are still higher than pre-pandemic levels.

The way forward

Currently, NREGA provides 100 days of labour per household. For years, multiple organisations have demanded to hike in the number of workdays. “It will be great, if they could hike it to at least 150 days. In my house, my mother and I have NREGA cards and together, we get to work for only 50 days each. Also, hiking the wage to at least ₹450 will do good,” says Aboobacker.

Explaining the history’s act, Madan Sabnavis, Chief Economist, Bank of Baroda, says that the scheme was formulated to initially provide seasonal employment to farmers when the weather conditions weren’t suitable for farming. “This was why the wage is capped at an average of ₹200, hiked keeping inflation in mind,” he says, adding, “NREGA is not meant for any asset or capital creation. So, the wages will be much lower than agriculture wages,” he says.

What could be the way to keep the scheme running going forward? “MGNREGA workers could be used in more sectors. However, it becomes difficult for the government bodies, considering a lot of jobs are allotted to contractors,” says Sabnavis.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.