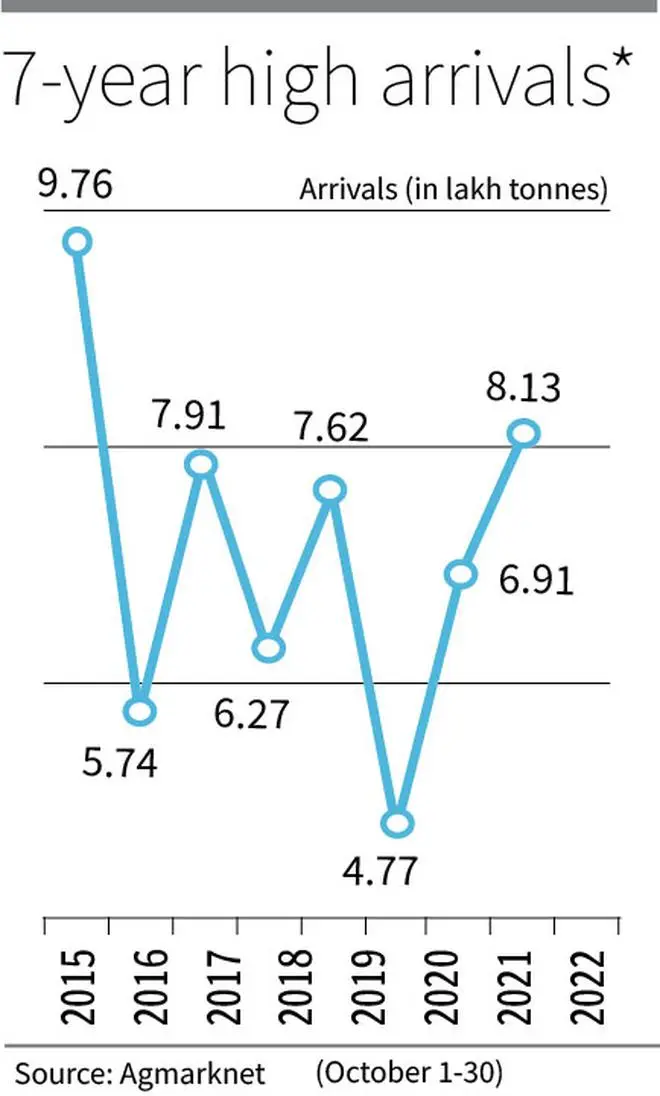

Wheat prices in India have soared to a record high in agricultural produce marketing committee (APMC) yards and wholesale outlets despite arrivals during October 1-30 increasing to a 7-year high.

The development comes amidst global wheat prices rising five per cent on Monday after Russia said it was withdrawing from the UN-brokered deal to permit grain exports in the Black Sea region.

“Wheat is delivered to flour mills in Delhi at ₹2,700 a quintal. For mills in Bengaluru, the price is ₹2,900-2,980,” said Pramod Kumar, President, Roller Flour Mills Federation of India.

Retail prices down

“Haryana is currently feeding the country with wheat. Punjab has no wheat and we are not able to understand where the wheat from Uttar Pradesh has gone,” said Adi Narayan Gupta, a Delhi-based flour miller.

According to Agmarket, a unit of the Agriculture Ministry, arrivals during October 1-30 were 8.13 lakh tonnes (lt) — the highest after 9.76 lt in 2015. For the entire season starting April 1, arrivals at 21.71 million tonnes (mt) are at a three-year high since the 23.73 mt inflow in 2019.

Wheat prices at APMC yards in the third week of October increased to ₹2,570.3 a quintal compared with ₹2,400.74 in the last week of September and ₹2,465.17 in the third week of September. Prices are well above the minimum support price (MSP) of ₹2,015. Last year, wholesale prices of the grain in the last week of October were at ₹2,068.4.

According to the Department of Consumer Affairs, the retail price of wheat on October 30 was ₹30.37 a kg — down from ₹30.99 a month ago. During the same period a year ago, the price was ₹27.63. Wheat flour (atta) prices are lower at ₹35.13 a kg from ₹36.13 a month ago. A year ago, it was ₹30.81.

Two reasons for surge

Millers and analysts attribute two reasons for the surge despite higher arrivals. One is that many mills do not have stocks that can help them manage the situation till the new wheat crop is harvested in February-end or early March.

The Centre not releasing wheat under the open market sale scheme (OMSS) this year is the other reason for the spike. OMSS helped mills procure the raw material at a low cost and thus control market prices and inflation.

“Overall wheat availability is low since we are discounting the amount of the foodgrain that was exported during March-May before the Centre banned shipments,” said S Chandrasekaran, an analyst.

During April-July this fiscal, 3.83 mt of wheat were exported compared with 1.49 mt in the year-ago period. Though the Centre banned wheat exports from May 13, it has been permitting shipments of the grain for which irrevocable letters of credit were signed before May 12.

“Maybe, production could be lower than the government’s estimates by a few million tonnes. Also, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) could have silently bought more wheat,” the analysts said.

OMSS significance

According to the fourth advance estimate of the Ministry of Agriculture, wheat production this year is 106.84 mt against 109.59 mt the previous year. It was lower than initial estimates of a record 111.34 mt.

Wheat production this year was affected by a heatwave that swept across the growing regions during March-April. The heatwave resulted in shrivelling of the grains.

The FCI procured 18.79 mt of wheat this year compared with 43.44 mt last year. Food Ministry officials said the 25 mt that could not be procured will have to come to the market but the analyst and stakeholders are sceptical.

“The Centre may have to release wheat under OMSS to control the price rise. It could release 2-3 mt of wheat to control immediately,” said Kumar.

“The wheat stocks the Centre expects to have may not be sufficient to meet the demand. The market might need 7-8 mt of wheat including for distribution through the Prime Minister Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) and National Food Security Act (NFSA) schemes,” said Sandeep Bansal of Grain Flour India Pvt Ltd.

Imports may be costly

Under both these schemes, the below poverty line people are supplied grains free of cost.

“Probably, wheat from UP which we say is missing could hit the markets in December,” said Gupta.

But Chandrasekaran said no one would risk holding wheat for that long, particularly when interest rates were rising.

Bansal said 2.63 mt of wheat would be required for PMGKAY and NFSA. “Probably, the Centre will have to dip into the buffer stocks. Or look for government-to-government imports,” he said.

“The Centre will have to compromise with buffer stock norms to ease prices,” said Rajesh Paharia Jain, a New Delhi-based trader.

However, imports could be a costly proposition currently with global prices rising to $8.71 a bushel ($320.26/₹26,525 a tonne) as of Monday.

Millers are, however, hopeful that the situation can be managed if stocks can last until January-end. They expect the new wheat crop to come in early.

According to the Agriculture Ministry, farmers have gone in for early sowing of wheat which could avoid this year’s bitter experience of heatwave affecting the crop. The area under the crop, too, is witnessing an increase.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.