There is a hue and cry about the recall of the ₹2000 banknote, notified by RBI on May 19, 2023. As part of the clean note policy, a similar exercise was done on January 22, 2014 when all banknotes issued before 2005 were completely withdrawn. The legal tender status was retained at that time too.

The public were given time till June 30, 2014 to exchange those notes. The same model is followed this time around, but media debates have adopted a needlessly alarmist tone. The RBI has given its justification in the press release besides uploading frequently asked questions for the public and separate guidelines to banks for smooth withdrawal of ₹2000 banknotes.

The current exercise is pretty small and cannot be compared to the November 8, 2016 demonetisation. At that time, the central government, in consultation with the RBI, decided to withdraw the legal tender status of ₹500 and ₹1000 notes, which together constituted about 86 per cent of the total value of the currency in circulation. Without the introduction of ₹2000 banknotes, it would have been difficult to quickly restore normalcy in currency circulation in 2016.

Falling circulation

According to the RBI press release, the value of ₹2000 banknotes, which was ₹6.73 trillion or 37.3 per cent of notes in circulation at its peak as on March 31, 2018, has come down to ₹3.62 trillion or only 10.8 per cent of notes in circulation.

The recall of ₹2000 banknotes is exclusively RBI’s decision as part of the clean note policy. Since the printing of ₹2000 banknotes was stopped in 2018-19, their use has dwindled significantly. The general public is unlikely to be discomforted by this decision as they are hardly using it for their day-to-day transactions. The window of more than four months is sufficient to either convert or deposit ₹2000 banknotes if a small amount of these notes is held by them.

The 2016 demonetisation exercise has been analysed threadbare. Although the direct assessment of such measures is difficult, it may have had a far-reaching impact. Despite growth slowing down since 2016-17, without hikes in tax rates, India’s tax buoyancy is pretty good in recent years, which is partly due to ill-gotten money coming back to the banking system and thereby reducing the opportunity to hide income. There is also evidence of a decline in counterfeit notes, terrorist activities, and drug smuggling as these activities are typically cash financed.

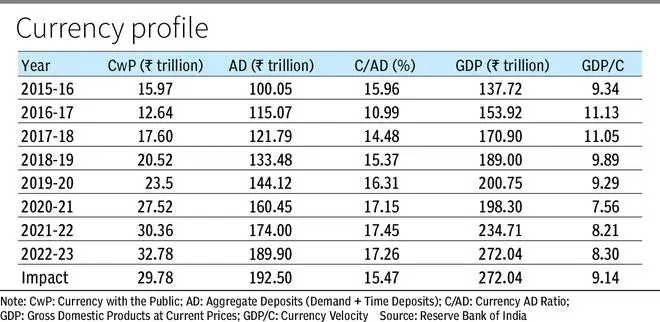

Despite commendable progress in digital transactions, India’s currency-deposit (C/AD) ratio remains high. The C/AD ratio, which was below 16 per cent in 2015-16, surpassed 17 per cent in 2022-23 (Table 1). Is it due to an increase in currency demand or currency hoarding?

Currency is unlikely to serve as a good store of value as its nominal return is zero and real return is negative due to inflation. Now street vendors, small traders and the general public prefer to pay in digital mode.

Currency hoarding

Hence, one would expect a fall in the demand for currency. If hoarding accounts for a high C/AD ratio, then ₹2000 banknotes are preferable as it requires less space and is relatively easier to transport and use for illegal transactions. Amidst a modest decline in currency velocity (GDP/C) from 9.3 to 8.3 during the same period, an increase in the C/AD ratio indicates currency hoarding.

For an objective evaluation of the current measure, let us assume that cash conversion of ₹2000 banknotes is limited to ₹62,000 crore, and ₹3 trillion may come back to banks as deposits. This would reduce currency with the public to ₹29.78 trillion and increase aggregate deposits (AD) to ₹192.50 trillion.

Consequently, the C/AD ratio and currency velocity may decline to 15.47 per cent and 9.14 respectively, slightly below the 2015-16 levels. Even this level of C/AD ratio is high compared to many peer-group countries. If deposit growth increases by ₹3 trillion exclusively due to the recall of ₹2000 banknotes, it would help reduce the gap between credit growth and deposit growth and thereby keep the lending rate under control, which is necessary to support growth in a tightening phase of the monetary policy.

Timing is key to unearth high denomination banknotes and simultaneously moderate the impact of the tight monetary policy provided the cash conversion is discouraged.

There is a positive correlation between cash transactions and illegal activities. Only a small portion of unearned income is indeed kept in the form of hard cash, other forms being real estate, gold, financial assets in India and abroad etc.

To reduce corruption, efforts are being made on all fronts — tax reforms, digitisation, formalisation of informal sectors, tightening anti-money laundering measures, electoral reforms, etc. The state can nudge the people to adopt non-cash transactions by providing a cost-effective mode of digital transactions. The introduction of central bank digital currency (CBDC) would go a long way in reducing demand for cash.

The writer is currently RBI Chair Professor at Utkal University and former Head of the Monetary Policy Department, RBI. Views expressed are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.