For a country that derives one-fifth of its GDP and more than 40 per cent of jobs from agriculture, we are surprisingly callous about the way in which the agricultural produce is priced, marketed and traded. Spot trading in most agri commodities is done in an opaque and de-centralised manner in mandis, short-changing farmers.

The trading of agricultural futures and options on stock exchanges is a way to address this lack of transparency in pricing; through backward linking of agri derivatives to spot markets. But policymakers have mostly looked at trading in agri derivatives with suspicion; some commentators have even compared commodity exchanges to a gambling den. This archaic view has led to frequent bans on commodity trading, apparently to check price increases and protect consumers.

There has been a string of such trading bans over the last two decades. In 2007, trading in derivatives of wheat, rice, tur and urad was banned, with only the ban on rice being lifted since then. Trading in sugar was banned in 2009 and lifted a year later. In 2008, a six-month trading ban was imposed on potato, rubber, chana and soy oil.

It was hoped that the stance towards agri derivatives would become more progressive once SEBI took over the regulation of commodity exchanges from the Forward Markets Commission in 2015. But the one-year ban on trading in paddy, wheat, crude palm oil, chana, soya bean, mustard and moong imposed in December 2021 shows that not much has changed and that commodity exchanges continue to be the scapegoat for policymakers wanting to be seen ‘doing something’.

Futility of ban

The futilit,y of such trading bans in controlling prices has been discussed and debated quite widely in recent days. The Abhijit Sen Committee which examined the influence of derivative trading on spot prices in 2008, did not find any conclusive evidence of a link between the two. The report noted that “Indian data analysed in this report does not show any clear evidence of either reduced or increased volatility of spot prices due to futures trading.”

If we consider the movement of CPI and WPI cereal and pulses indices (see chart), the trading ban in December 2021 did not have any influence on inflation in this category. Inflation surged sharply immediately after the trading ban, in January and February 2022, due to global supply shortage and increased demand on the reopening of the economy. The Ukraine incursion, of course, led to prices of agri products skyrocketing, exacerbating inflation, proving the ban in December 2021 completely ineffective.

What’s more, in periods of crisis such as this, the presence of a derivatives market is of utmost importance for farmers and commodity users to shield them from price risks. Absence of futures and options on critical commodities in the initial period of the Russia-Ukraine crisis would have cost users dearly.

Secondly, the presence of a derivatives market helps in checking unbridled price increase since the short-sellers begin squaring their positions after a certain level, thus halting upward movement of prices. The knee-jerk trading ban in December has thus proved counter-productive in controlling prices.

Bleak future for comexes

India’s trade in cotton and spices had made it one of the richest countries, before colonisation stripped us of all the resources and skills. A transparent, deep and credible spot and commodity market can go a long way towards improving agri GDP, contributing to overall growth.

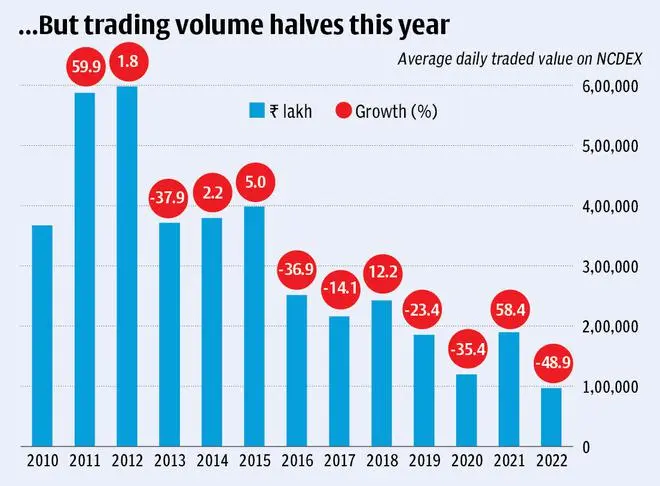

But instead of taking steps to boost activity, traders and investors are being driven away from markets due to ad hoc policy actions. The average daily traded value on NCDEX, the largest commodity exchange in India, has dropped from ₹1,897.74 crore in 2021 to ₹970.10 crore in 2022. With some of the most liquid agri contracts banned, trading activity has plunged.

Of concern is the fact that agri trading in India had been sliding over the last decade. Daily traded value in 2022 is just 16 per cent of that in 2012. The credibility of commodity derivatives was eroded significantly after the NSEL scam in 2013; daily trading value plunged 38 per cent in 2013 compared to 2012; and has not recovered since.

Regulatory uncertainty tends to impact trading sentiment and volume considerably. Sudden trading bans make traders exit permanently from the segment. Research shows that trading activity seldom picks up in commodities that have faced trading bans.

What next?

As a first step, policymakers need to understand the futility in exchange trading bans in controlling spot prices. Prices can be controlled by regulating imports and exports and tariffs on external trade, stock holding limits and so on. Banning futures and options is regressive, very rarely used globally.

Not only should the trading ban be revoked, SEBI has to communicate to all market participants that such measures will not be taken in the future. This is imperative to restore confidence among market participants and to bring them back to the bourses.

Efforts need to be made to increase activity and participation in agri commodity futures and options. This can help serve as a powerful tool for helping price discovery in the spot market.

And, most importantly, the eNAM project — which seeks to create a single national market for agri commodities through a pan-India electronic trading portal networking all the existing APMC mandis — needs to be expedited. The progress of this project, which began in 2016, has not been too good.

A unified electronic spot market for agri commodities will create a strong base for agri derivatives. The electronic spot and futures market, together, can improve realisations and risk management for farmers and industrial users.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.