Food and agriculture marketing in emerging economies is experiencing a wave of being promoted on digital platforms. India is no exception to this. The Ministry of Agriculture and Farmer Welfare launched the electronic National Agriculture Market (eNAM)–Platform of Platforms (PoP) on July 14, 2022, as a mobile application in 12 languages.

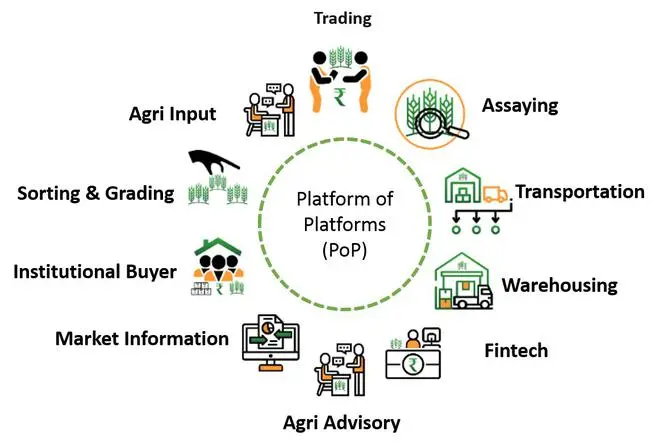

The PoP dashboard includes a score of services: trading, assaying, transportation, warehousing, financial services, agri-advisory/ extension services, market information, assaying, institutional buying and selling, and agricultural inputs services (see Figure 1).

eNAM came into existence in April 2016 and has integrated about 1,260-odd APMCs that account for only 17.21 per cent of the total 7,320 APMCs including 4,843 sub-market yards. In 2016, 585-odd APMCs were combined with the eNAM portal, and the Agricultural Technology Infrastructure Fund channelized ₹200 crore to set up the required infrastructure in these APMCs for e-auctioning of produce, and disseminate a fair price to physical market participants. While it has benefitted about 1.73 crore farmers and 2.25 lakh traders through its six-year journey, its outreach is skewed to a few States. eNAM has effectuated a single-point levy of market fees and a unified licensing system for traders and commission agents.

Figure 1

The agriculture marketplace has observed a staged development, say eNAM 1.0 as a portal to eNAM 2.0 for promoting warehouse-receipt (eNWR) trading and direct marketing of farmer produce (through the APLM Act, 2017) and eNAM 3.0 by unveiling the PoP app-based module. However, it has yet to gain considerable traction in the agricultural trade by integrating the remaining number of APMCs.

Concerns

The national government intends to ensure the agri-value chain actors come under one roof and avail and access the bundling of products and services at a one-stop shop through eNAM-PoP. However, a few issues concerning the discourse on the political economy of agriculture, corporatisation of food systems, and the power of vertical integration have emerged that call for a debate and discussion.

What can PoP deliver to farmers and diverse stakeholders of agri-food value chains, and are these services cost-effective?

Can disruptive technology innovation transform the agriculture market into a unified phygital structure, and integrate the market with the Global Value chains (GVCs)?

How can the government incentivize the access and nature of usage of the eNAM-PoP services?

Way forward

First, eNAM-PoP would provide a value architecture to the diverse agri-food value chain actors. The architecture should perform four functions: discovery, matching, transaction, and evaluation elements. In other words, PoP should be a dynamic, interactive, and strategic fit with the Agricultural Market Information Systems.

The PoP can amplify direct and indirect network effects for farmers or FPOs, agricultural inputs and outputs entities, and market infrastructure institutions. The network effect can reduce the ex-ante (search and negotiation) and ex-post (monitoring and enforcement) transaction costs for onboarded actors on the platform.

Transaction data and their security registry could be maintained using a blockchain-enabled Distributed Ledger Technology, while transactions can be enabled through a smart contract embedded in PoP. The coupling of software solutions and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) can be added to the platform architecture.

Second, PoP can enable farmers to access the new or missing markets, compare prices of several commodities, and sell the assayed and certified produce to traders and bulk buyers through the PoP mobile app. Farmer collectives or FPOs can access the location of warehouses or market yards given the proximity and contact the empanelled service providers of eNAM PoP and avail of such services. For example, Aryadhan, a fin-tech services provider, would extend trade finance options and offer real-time payments to FPOs.

Third, upstream and downstream marketplace models seem to have harnessed the untapped potential of agricultural markets. However, they are yet to be time-tested platform business models in the agriculture field. The strategic management group of eNAM can draw some lessons from unveiled marketplace models and improvise the PoP roll-out and upscaling. The agency problem, economic viability, and sustainability of the eNAM-PoP need to be explored. Otherwise, promoting cross-border trade and integrating with the GVCs by transforming the physical market into a phygital structure would remain a distant reality.

Fourth, stakeholders’ incentive design is necessary to sustain and scale up eNAM-PoP. A robust governance mechanism must be aligned with the PoP design and its roll-out to improve coordination between users and those complementing the platform and reduce the power asymmetry between stakeholders – directly and indirectly associated with the platform.

Fifth, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmer Welfare, Small Farmers’ Agri-business Consortium, and the empanelled strategic management group and those complementing the platform need to chart the scaling strategy for PoP – considering the network loop, data loop, and capital loop.

While the rising regulatory complexity, risks, and regulatory arbitrage in agriculture can arrest the magnitude of scaling, the success of PoP would depend on diverse actors’ participation and willingness to pay for services that should favourably compare with the offerings of platform capitalists.

Dey is Faculty and former Chairman of CFAM and Dixit is Academic Associate of ABM, IIM Lucknow. Views are personal.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.