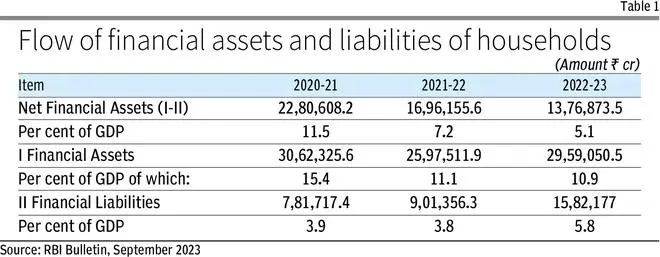

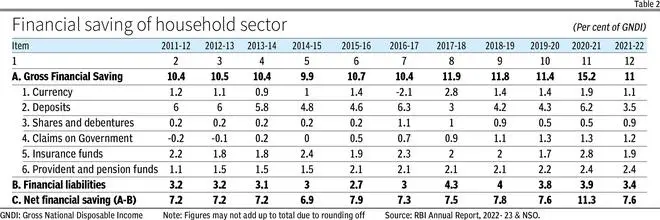

Household sector’s savings in financial assets has shown a sharp decline to 5.1 per cent of GDP in 2022-23 (Table 1). From 2011-12 to 2019-20, the financial savings of the household sector have moved in a narrow range of 7 to 8 per cent of Gross National Disposable Income (GNDI) (Table 2).

In 2020-21, it touched 11.3 per cent during the Covid period. That was a lone exception. In 2021-22 the financial savings of household sector was 8.3 per cent of GDP. Is the sharp fall in 2022-23 a matter of concern?

This fall in household financial savings can be explained in terms of changes in household financial assets and liabilities. Compared to the pre-Covid five-year average over 2015-16 to 2019-20 which was 7.8 per cent of GDP, the 5.1 per cent figure is lower by a margin of 2.7 percentage points.

This fall is made up of 2.2 percentage points of increase in change in gross household financial liabilities and 0.5 percentage points fall in change in gross household financial assets over the corresponding periods. There was a sharp rise in bank advances including personal loans in 2022-23 as compared to pre-Covid years.

In fact, bank advances as percentage of GDP amounted to 2.5 per cent in 2019-20 which increased to 4.5 per cent in 2022-23. RBI’s monthly data covering the period April to July 2023 shows an average growth of 19.5 per cent in outstanding bank advances for the household sector, indicating continuing persistence of this trend.

If the fall in financial savings ratio of the household sector is a phenomenon of one year, we can ignore it. If it persists, it has many implications. Second, for understanding the household sector, should we look at Net Financial Assets or Gross Financial assets.

Gross Financial Assets as a percentage of GDP stood at 10.8 per cent in 2021-22 and 10.9 per cent in 2022-23. Even earlier, except for 2020-21, Gross Financial Assets as percentage of GNDI was in the range of 10 to 11 per cent.

Financial liabilities rise

The reduction in the net financial assets rate is primarily due to a rise in Financial Liabilities. There can be many interpretations of this rise. An optimistic interpretation of this rise in the borrowings of household sector which also includes non-corporate businesses is that this sector is buoyant and has borrowed more. Nevertheless, the fact is that net financial savings ratio of the sector has come down.

That is, the transferable savings ratio of the economy has come down and this will affect the borrowing programme of government and corporate sector.

For example, the rule that the acceptable level of fiscal deficit of the Centre and the States taken together can be 6 per cent of GDP is based on the assumption that household savings will be around 7 per cent of GDP and the net inflow of resources from abroad will be around 2.5 per cent of GDP.

This borrowing space of 9.5 per cent of GDP could be shared by the government to the extent of 6 per cent of GDP, and by the public sector enterprises to the extent of 1 to 1.5 per cent of GDP, leaving the remaining borrowing space of 2 to 2.5 per cent for the private corporate sector.

Budget stress

Thus, if the savings rate of the household sector fell to 5 per cent of GDP permanently, we cannot have the 6 per cent rule. The fiscal deficit will have to be lower. This will put the budgets under a stress. The way out is to ensure that Gross Financial Assets of household sector go up, if financial liabilities are to rise.

Comparing the pre-Covid average over 2015-16 to 2019-20 with 2022-23, gross financial assets of household sector have fallen only marginally to the extent of 0.5 percentage points of GDP due mainly to a fall in bank deposits. We cannot afford to let the household sector’s financial savings rate fall. Household sector is the only surplus savings sector in the economy. The other two sectors — government and corporate business sector are net borrowers.

In drawing any conclusion about the savings behaviour, we should be careful to note that computing net financial assets is a way of estimating financial savings. We do not have direct data on savings. What is being done is to estimate it through indirect methods. By looking at the elements in the procedure adopted to estimate savings, no conclusion on behaviour can be made.

However, if at the end of computations, the estimate is that savings are down, it is a matter of concern. Perhaps, we should wait and see whether this is a one-off phenomenon.

Rangarajan is former Chairman, Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council, and Former Governor, Reserve Bank of India. Srivastava is former Director and Honorary Professor, Madras School of Economics. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.