After the wheat export ban, the government decided to restrict sugar exports, setting a cap of 10 million tonnes (mt) for the current marketing year of sugarcane crop. India is the world’s largest producer of sugar and the No 2 after Brazil.

The Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) notified the ban on export of sugar from June 1 beyond the quota limit. The key reasons cited are to ensure domestic availability and price stability under rising inflationary pressures. It is also aimed at orderly trade in the context of ever-increasing export shipments of sugar breaching the previous records of more than 7.2 mt.

The government is also concerned over the threat of food crisis caused by supply-chain disruption(s); hence one dimension of export restriction is also aimed at supplying sugar to countries in economic distress, and friendly nations thus increasing India’s diplomatic outreach along with taming speculative trading.

But the political economy of sugar export restriction goes well beyond the reasons cited. The other reasons for the export ban are, first, the government intends to encourage ethanol blending. India is about to touch the target of 10 per cent ethanol blending, with 9.99 per cent already achieved in March.

Incidentally, the Union Cabinet amended the National Policy on Biofuels on May 18 by approving the decisions of the National Biofuel Coordination Committee (NBCC). One decision is to advance the ethanol blending target of 20 per cent in petrol to Ethanol Supply Year (ESY) 2025-26 from 2030. India took a cue from Indonesia and Brazil which have respectively increased the blending of bio-fuel by 30 per cent and 20 per cent to deal with burgeoning energy prices. In fact, ethanol is cheaper, costing merely around ₹65 per litre in comparison to petrol of around ₹96.

The export ban is also aimed at enhancing the use of domestic sugar molasses towards ethanol production. India has been offering subsidies on export of sugar as the Indian sweetner is priced-out in international markets, thus costing the exchequer.

WTO pressure

Moreover, India has lost a sugar subsidy dispute against Brazil, Australia and Guatemala in the WTO. The WTO has advised India to withdraw its sugar subsidies as they are not consistent with the WTO Agreement on Agriculture and the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures.

Recognising these challenges, utilising sugar for ethanol will serve two purposes — first, reducing the burden of ever-increasing crude oil imports at high prices coupled with reducing the burden of export subsidy and potential trade dispute(s) at the WTO. There is logic in enhanced production of ethanol as it supports farm income, offers cheaper fuel solution, lower dependency on fossil fuels, and reduces pollution as ethanol is non-toxic and biodegradable.

Further, it will develop an eco-system of enhanced production of bio-fuels thus supporting the farm income, a sector which is widely distressed.

Bumper crop

Secondly, the argument that export curbs will enhance domestic supplies and cool inflationary pressures has limited merit as the country’s sugar output is expected to touch a record 35.5 mt.

Further, it is reported to be holding stocks of 6-7 mt from the previous marketing year. India’s sugar industry is upbeat on a bumper production with Skymet and IMD predicting a normal monsoon.

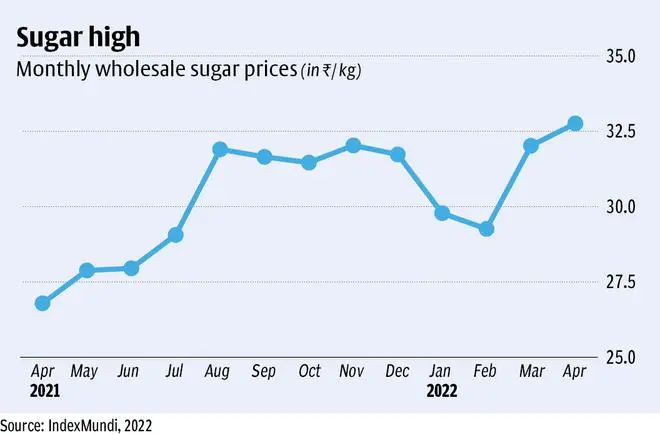

The data of sugarcane sowing from all prime producing States Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Karnataka vindicates the satisfactory trends, supported by both manual feeding of sowing data and validated by Global Positioning System. Sugar prices remained largely stable in the last one year (figure 1) with a noticeable increase in March, perhaps because of the rising cost of transportation with the increase in prices of diesel. The production, stock-holding and consumption data (27-28 mt) indicates that there is adequate supply of sugar in the country.

Thirdly, the export restriction is motivated by external developments such as lower sowing of sugarcane in Brazil due to Covid-19 protocols and associated labour shortages along with harsh weather conditions. So the reduced exports from Brazil has increased the demand for Indian sugar in the world market. So, to safeguard domestic availability of sugar the government has opted to limit exports.

Fourthly, the world economy is passing through a difficult phase with a series of economic disruptions, starting from the Covid-19 pandemic, container shortages, escalating freight charges, economic and trade sanctions, financial and commercial boycotts, and supply chain disruptions caused by the Russia-Ukraine war.

All these developments have led to rising food protectionism around the world, as major producers curb agricultural exports, adding to the supply shock and enhanced price volatility in the international market. An economy with 1.4 billion people to feed, India needs to carefully plan to manage its internal political economy.

Finally, in the current geopolitical scenario, there is a view to move with caution as these commodities (wheat/sugar) can provide us a diplomatic leeway to serve the humanitarian needs of countries that may have to endure extreme supply-shocks.

Needless to reiterate, it is an export restriction not a ban, meaning India will continue to cater to genuine requests of supply of sugar up to the prescribed export limit of 10 mt. It is a good move to leverage the diplomatic value in the global sugar trade scenario by restricting its supply but India must recognise that its ambition to evolve as a regional power can only be fulfilled if it emerges as a key supplier to the global economy.

Ram Singh is with Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi, and Surendar Singh is with FORE School of Management, New Delhi. Views expressed are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.