When the Covid-19 pandemic struck in the first quarter of 2020, the central banks of advanced economies decided to hurl the kitchen sink at their economies, which meant printing unlimited amount of money and distributing it among their people. The RBI, however, adopted a far more conservative approach, turning away from ‘helicopter money’, which some economists advocated. But despite this guarded approach, the Indian central bank’s balance sheet has increased over 50 per cent during the pandemic.

The predicament in which the RBI finds itself in is, however, less challenging than the situation that other central banks such as the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and the Bank of England face. These central banks had been printing money to stave off recession since the global financial crisis in 2008. Their assets and liabilities were therefore already elevated at the onset of the pandemic. The pandemic-related stimulus has only made matters worse.

For instance, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet was around $900 billion in July 2008. It expanded to $4.17 trillion by February 2020 and further to $8.7 trillion by December 2021. The trajectory is similar for the ECB and the Bank of England, as these central banks couldn’t stop pumping money into their economies since 2008.

Such unbridled monetary expansions have consequences, as outlined in a paper from Bank of International Settlement, written by Jaime Caruana, ‘Why central bank balance sheets matter’. The paper points out that expansionary policies have implications for both real and financial sectors of the economy; impacting inflation, endangering financial stability, causing financial market distortions and creating conflicts in sovereign debt management.

The US Fed and other central banks have, therefore, devised an exit strategy by allowing a portion of the securities which are maturing, to expire. The RBI has not laid out any specific schedule, but its holding of domestic and foreign securities is beginning to move lower.

RBI during Covid

Since RBI’s accounting period was from July to June until FY21, the excruciating period in the first quarter of the pandemic was captured in the accounts of 2019-20. As economic activity came to a standstill following the lock-downs in the first few months of the pandemic, government support was needed to help the distressed segments of the economy. The RBI had to roll out a series of lifelines to borrowers as well as back the government borrowing which had shot up in this period.

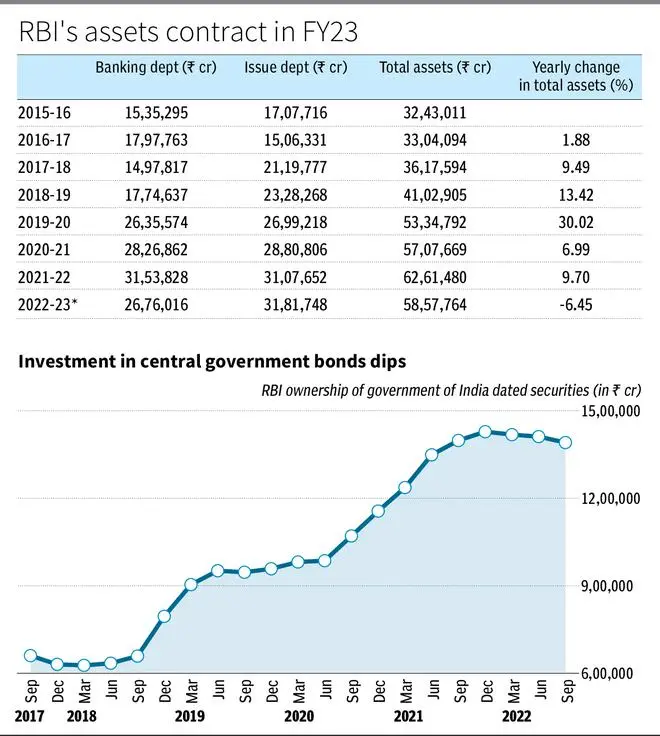

The central bank balance sheet witnessed the sharpest jump in recent years in 2019-20; growing 30 per cent, to ₹53.3-lakh crore.

The growth in FY21 and FY22 was however more moderate, at 6.99 per cent and 9.70 per cent, despite the central bank having to buy government securities through open market operational and G-SAP (government securities acquisition programmes) to address the demand-gap for G-secs. Foreign securities increased as the strong foreign portfolio flows were mopped up to increase forex reserves, though the reduction in Cash Reserve Ratio in this period may have reduced the liabilities somewhat.

The RBI’s assets have grown roughly from ₹41-lakh crore to ₹62-lakh crore between FY19 and FY22.

This expansion needs to be corrected for various reasons. Besides the inflationary impact and the financial market disruption, there is also market risk. Central banks’ assets are mainly held in the form of domestic and foreign assets. The value of the investment could decline while the vale of liabilities remain the same. This can create problems in meeting payment obligations.

The contraction begins

The good news is that the contraction of RBI balance sheet has already begun. Going by the data published by RBI, total assets held by it have declined to ₹58.57-lakh crore as on October 28, 2022. This is 6.45 per cent lower compared to the assets of ₹62.61-lakh crore held towards the end of March 2022.

The contraction seems to have been the result of many factors. One, the sharp rupee depreciation in this fiscal year resulted in the RBI using its forex reserves, accumulated during the pandemic, to defend the currency. This accounts for the decline of 32 per cent in balances held abroad, down ₹3.97-lakh crore.

Recent increase in CRR by 50 basis points in May this year could have resulted in slight improvement in bank deposits with the central bank, but with demand for credit improving, short-term money parked by banks with the RBI under the LAF corridor has shrunk.

Of greater interest is the fact that RBI’s holding of dated government of India securities is coming down. Towards the end of March 2022, the central bank held around ₹14.17-lakh crore of dated government bonds. The holding had reduced to ₹13.9-lakh crore towards the end of September. This implies that the central bank has begun reducing its holding of G-secs in a calibrated manner. An effort to control domestic investments at these levels will be welcome.

A difficult road

But the exit is unlikely to be easy, especially with growth being quite nebulous, threatened by host of external risks. The winding down of the securities accumulated over the last few years is likely to move in fits and starts and take time. With the fiscal deficit likely to be elevated due to the additional expenditure having to be borne by the government to support the economy, public debt management will continue to pose difficulties.

But it is good to see the resolve amongst central banks to reduce the assets held by them as that is the way forward in controlling inflation and in ensuring sustainable growth.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.