Water is paramount for economic development and poverty reduction. But the water-related news coming from different quarters in recent years is worrisome. The United Nation’s water website mentions that in the early to mid-2010s, 1.9 billion people or 27 per cent of the global population lived in severely water-scarce areas. But this number will increase to 2.7- 3.2 billion people by 2050.

The Water and Related Statistics (2021), published by the Central Water Commission of India, mentions that one out of three people will live in a water-stressed area by 2025. These suggest that there is an urgent need to augment the water supply wherever possible to avert the looming water crisis.

But unfortunately, the small water bodies (tanks and others) which have been supporting the agriculture and domestic requirement of water for many years in India are fast vanishing now.

What is the state of small water bodies (SWBs)? Why is the area irrigated by SWBs declining at a faster pace? Given the increased demand for water, can we afford to ignore SWBs?

Though small in size, the benefits derived from SWBs are enormous. Since these are spread in all parts of the country, they provide easy access to water for all purposes — domestic needs, animal husbandry, drinking water and agriculture. SWBs have several distinct features from other water sources (canal and groundwater). Because of their small size, they can be easily managed.

The maintenance cost of this water source is low compared to that of canal irrigation, which has increased phenomenally over time.

The command area of most SWBs is normally small, irrigating 100-500 acres. This allows distribution of water effectively, without any conflicts between tail-end and head-reach farmers, which is common in canal command areas. It helps reduce the poverty of resource-poor small and marginal farmers who are the main beneficiaries of SWBs.

The increased water storage from SWBs also helps increase groundwater recharge. Importantly, as SWBs are located in every village, women do not have to walk far to fetch water for their drinking needs.

Current status

These SWBs, which have met all the water needs for centuries, are now rapidly declining in terms of numbers and area irrigated. Studies show that rainfall is not the main reason for this. Continuous encroachment on catchment areas and flow canals that carry rainwater to tanks, lack of annual maintenance of tanks by allocating adequate funds, etc., are some of the reasons for the reduction of irrigated area by SWBs.

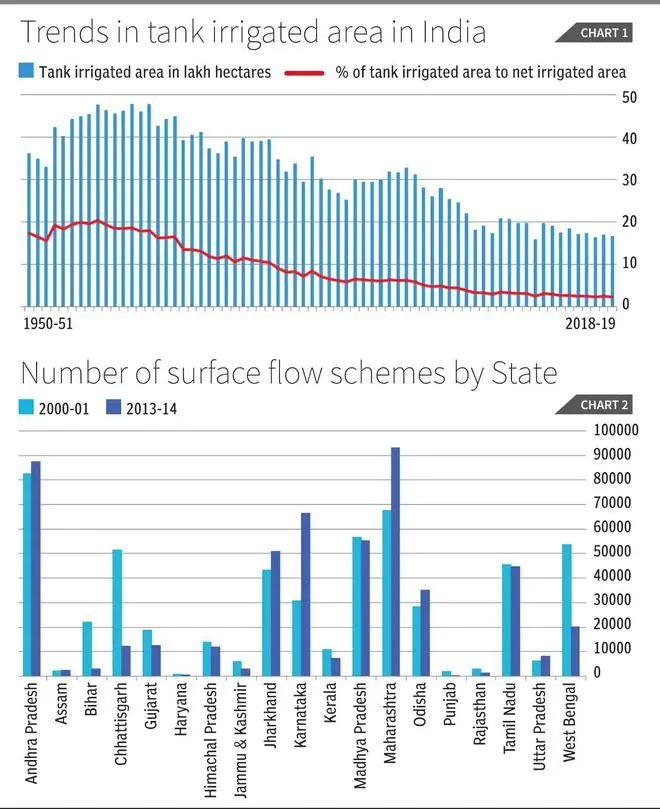

From 46.30 lakh hectares (lha) in 1960-61, the area irrigated by tanks in India declined to 16.68 lha in 2019-20. As a result, the share of tank area in India’s net irrigated area (NIA) declined from 20 per cent to 2 per cent during this period (Chart 1).

In States like Tamil Nadu, where tank irrigation accounted for one-third of irrigated area in the 1960s and 1970s, the area under tank irrigation declined from 9.36 lha to 3.72 lha during this period.

Due to this, the farmers who were completely relying on tank irrigation for the cultivation of crops have left agriculture or kept the land fallow. Surprisingly, even in years with good rainfall, the area irrigated by tanks has not increased in Tami Nadu. The same trend is seen in other States too.

The urban agglomeration witnessed from the 1990s has severely impacted SWBs, turning many of them into dumping grounds. The Standing Committee on Water Resources (2012-13) underlined in its 16th report that most of the water bodies in the country were encroached upon by State agencies themselves.

The civic body at large remains silent when encroachments of water bodies happen under its very nose. Besides reducing the water storage capacity of the SWBs, the continuously increasing encroachments also lead to widespread flooding during the monsoon season.

The 5th Minor Irrigation Census, published in 2017 by the Ministry of Water Resources, underlines that the number of surface minor irrigation schemes has declined from 6,01,000 in 2006-07 to 5,92,000 in 2013-14; reduction in the number of SWBs is observed in most States (Chart 2). According to the Standing Committee on Water Resources (2012-13), about one million hectares of irrigation potential was lost due to encroachment and other reasons.

Looking ahead

Policymakers must understand that if SWBs continue to be neglected, the recharge mechanism of wells will collapse. In such a case, even wells will not have water. Already, there is a warning signal from the Central Groundwater Board which tells that the number of blocks classified as over-exploited/critical/semi-critical has increased from 1,645 in 2004 to 2,538 in 2020.

All these indicate that the small water bodies need to be repaired, restored and renovated. First of all, considering the ever-increasing encroachments, strong legislation should urgently be enacted to make encroachment on water bodies a cognisable offence.

Following the judgment of September 6, 2014, by the Madras High Court Madurai Bench, approval for the layout or building plan on lands located on SWBs should not be given.

Understanding the dying state of SWBs, a separate Ministry for Small Water Bodies should be created with adequate funding to conduct periodic repair and rehabilitation works. Without the participation of farmers who are the main beneficiaries of SWBs, it is difficult to improve the performance of these age-old oases.

Therefore, farmers must voluntarily come forward to set up a tank users’ organisation and undertake the repairing of SWBs, as followed earlier under the age-old Kudimaramathu system. Since corporates are increasingly using water for various purposes, they should be asked to repair and renovate SWBs under the ambit of corporate social responsibility. If swift actions are not taken to save SWBs, they will slowly disappear and the water woes will aggravate.

The writer is former full-time Member (Official), Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, New Delhi. The views are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.