The recent strike down of Credit Suisse’s AT1 bonds has brought with it flashbacks of the similar write down of YES Bank’s additional tier-1 (AT-1) bonds in March 2020.

Even as bondholders’ continue their legal battle against YES Bank and RBI for the write down, the global precedence set by the Swiss regulator for a systemically important bank, might be reflective of a rude reckoning for domestic bondholders who have alleged mis-selling on part of the bank.

The major reason why YES Bank and the RBI were dragged to court over the write-down was incomplete or lack of disclosures, and the fact that the bonds were sold to retail investors in the garb of “super FD” or high-yielding, safe debt instruments with fixed returns of around 9.5 per cent at five-year tenure. The Delhi High Court, in turn, ruled that it wasn’t correct to write down the AT-1 bonds for technical reasons and not mis-selling.

The Supreme Court, where the matter has escalated to, has sought category-wise details of bondholders and this is interesting. YES Bank has alleged that most investors are ultra HNIs and top layer of investors, who were aware of the inherent risks. It has also contested that bondholders’ contention should be with the intermediaries and brokers that mis-sold them the bonds and not with the issuer bank.

These intermediaries include financial institutions such as Indiabulls Housing Finance and arrangers or processors such as Karvy that either had lending relationships with YES Bank, or bought AT-1 bonds in bulk in exchange for better rates or more business. In short, it may be a quid-pro-quo deal. But ironically, Indiabulls Housing Finance and Karvy are now part of the petition against YES Bank, appealing against the write-down due to the huge losses made on the bonds left on their books.

A 71-year-old widow and senior citizen said her relationship manager at YES Bank advised her to invest her entire retirement corpus of ₹1 crore in the bank’s AT-1 bonds. “Nowhere in the term sheet was it mentioned that that these are Tier-I or perpetual bonds. But it clearly states that the seller is Indiabulls Housing Finance and the issuer is YES Bank,” she told businessline.

A former YES Bank branch manager, on condition of anonymity, said retail banking branches were asked to pitch AT-1 bonds as safe medium to long-term investments. “Because they were unavailable in the primary market, these bonds were being resold on behalf of other financial institutions, including broking agencies who had underwritten the bonds,” he explained.

Delving into details

According to SEBI, 1,346 individual investors had invested approximately ₹679 crore in YES Bank’s AT-1 bonds, of which, 1,311 were existing customers of the bank who invested ₹663 crore in these bonds. Further, 277 customers had existing FDs with the bank, which were prematurely closed, and nearly ₹80 crore reinvested in AT-1 bonds. Nippon Mutual Funds, Barclays, Kotak Mutual Funds, Franklin Templeton, 63 Moons, Indiabulls Housing Finance and Reliance Industries are some of the institutional investors to the bonds.

What might complicate the matter is the lack of a centralised database, making the secondary market sales of bonds difficult to determine the exact number of retail investors. The only solace is that post the YES Bank debacle, AT-1 bonds have become a niche play as the investment threshold was increased to ₹1 crore from ₹10 lakh. It’s now strictly for HNIs and super HNIs. Yet, the crisis at Credit Suisse has reignited the debate on whether these instruments should be retail investors’ option, given the risk of capital wipe out.

While this is one side, the apex court has prioritised on determining whether bondholders deserve to be compensated, the rationale for subscribing to the bonds that they had to be resold, what was the possible arrangement, if at all, between the bank and these corporate / institutional houses. The verdict may also set precedence to ensure what can be done to avoid such a mess in the future.

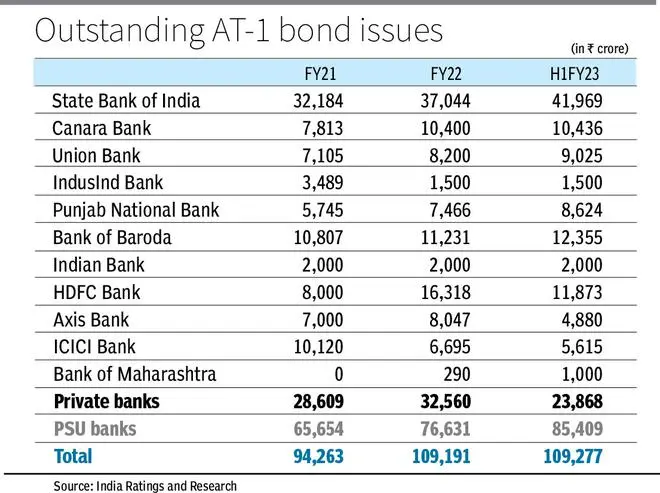

Indian banks’ exposure to AT-1 bonds is less than a per cent for private banks and 1-2 per cent for PSU banks. Most AT-1 bond issuers are PSU or top-rated private banks with low credit and liquidity risk. But the inherent risk is that of pricing.

“If you see a five-year HDFC bond today, it’s trading around 8-8.05 per cent, whereas SBI’s AT-1 bond, with a five-year call option, is at the same level of 8.10-8.20 per cent. Despite SEBI marking perpetual bonds as 100 years, investors are treating it as a five-year instrument,” said Venkatakrishnan Srinivasan, Founder and Managing Partner at Rockfort Fincap, adding that AT-1 bonds should be priced at least 100-200 bps higher depending on the issuer.

Where is the parity?

What is also being lost in the noise is that the regulator wrote down the AT-1 bonds, which have a quasi-equity characteristic, but ranking higher than equity shares as per the waterfall principle of repayment, but allowed equity investors to remain invested albeit with the three-year lock-in that just ended.

While one might cite the USB-Credit Suisse deal, the difference between the two is that the write-down of Credit Suisse’s AT-1 bonds and acquiring the bank at a 60 per cent discount to the market price was a commercial decision taken by USB and not the regulator. To be sure, the YES Bank’s rescue was a part of the reconstruction scheme formulated by the RBI to save and revive the bank through capital infusion by a consortium of institutional investors led by State Bank of India.

The decision to place shareholders over bondholders is a larger issue. A secured instrument isn’t protected, unsecured instrument had recourse. Whose interest is really being protected? The Apex court verdict should reveal.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.